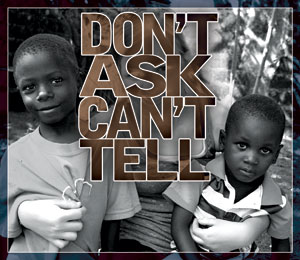

ALUMNI | I am a humanitarian aid worker in _______. If I fill in the blank with the name of the place where I work, and it somehow becomes known to the authorities here, I run the risk of being expelled from the country. This is often the dilemma of aid workers in the midst of an armed conflict: The reality we experience is rarely, if ever, what is presented by the media. There is so much we would like to say and we need the public to know, but most of the time we cannot tell you.

There is a long-running commentary in the U.S. about liberal or conservative bias by major media outlets. Here, when journalists dare to question the policies or motives of civilian or military authorities, they are frequently threatened, harassed, interrogated, jailed or killed with impunity; few if any of these cases are credibly investigated.

Historically, humanitarian workers enjoyed a protected status under the Geneva Conventions as non-combatants whose objectives are to ensure that civilians affected by conflict have access to food and water, basic shelter and medical care. Over the past 15 to 20 years, however, humanitarian workers have increasingly become the targets of terrorist groups, militias and even governments. My current location has earned the dubious distinction of being one of the worst places in the world for both journalists and humanitarian workers. The last person who said that publicly was kicked out.

On a near-daily basis, we visit some of the thousands of civilians who are suffering from the effects of the conflict here. They are citizens of this country, who have lost almost everything—their homes, their land, their means of livelihood, their loved ones. Both parties to the conflict bear responsibility for those losses. If I openly say this, I might be accused of supporting the rebels’ cause and undermining the government.

Hundreds of thousands of these civilians have miraculously survived intense fighting, though they are physically and emotionally wounded, malnourished and traumatized. If I say that publicly, my visa could be rescinded.

Now that the fighting has stopped, the civilians have been forced into barbed-wire enclosed military camps, which are far below accepted minimum standards in almost every way. If I tell you that, my organization could be denied access to the camps.

These civilians have not been found guilty of any crime, nor is there any legal basis for their detention. And yet they have been deprived of their freedom, their right to family unity, adequate shelter, food, health, sanitation and their dignity. If I say this out loud, I might be expelled from the country, putting the organization’s national staff at risk and jeopardizing the possibilities for recruiting new staff.

After months of advocacy with the authorities to release these people, there were signals that a large release would take place. The next day, a headline in a major newspaper read, “10,000 Refugees Freed.” In fact, it was only 1,800 (not 10,000), they were not refugees (you have to cross an international border to be a refugee), and they were not freed (they were put into other camps, just a little closer to home).

But I can’t tell you that.

Editor’s note: This article continues a UD Messenger series called “First Person,” in which alumni share their professional or personal expertise. In this case, the writer, who earned a master’s degree at UD in international relations and who must remain anonymous in order to continue to work, has been an international aid worker for the past several years.