Brandon Bies, AS ’01, has been garnering widespread media attention in recent months as he discusses a subject that was a national military secret for more than half a century.

Bies, a history and anthropology double major, has been featured in major media venues including The Washington Post and National Public Radio’s All Things Considered for his efforts to help a group of World War II veterans tell their story about an ultra-secret prisoner of war camp known to the outside world as P.O. Box 1142. The military intelligence units in which these men worked were based at Fort Hunt, Va., a park that originally housed a coastal defense installation on the Potomac River to guard the nation’s capital during the Civil War.

A cultural resource specialist for the National Park Service, Bies has been helping an ever-dwindling number of GIs who were stationed at the fort tell about guarding and interrogating some of the highest-ranking officers, party leaders and scientists of Nazi Germany. While the details of the intelligence gathering operation at Fort Hunt have surfaced through the release of classified government documents, the soldiers who served at the base—many of them German Jewish immigrants who lost family members in the Holocaust—had always kept their mission secret.

The stories started to come out after a park ranger mentioned the newly declassified documents during a tour he was leading, Bies recalls, adding, “At that time, the park rangers…were not sure that any of the men who served at Fort Hunt were still alive.” But someone taking the tour remarked that his neighbor, Fred Michel, had been stationed at the fort during World War II.

“I began having phone conversations with Fred Michel, who was living in Louisville, Ky.,” Bies says. “He was 86 years of age at the time and told me that he had interviewed some very high-ranking German scientists and generals during his time at Fort Hunt.”

This initial contact was enough to convince Bies’ superiors in the National Park Service to send him to Louisville, he says, where he spent three days interviewing Michel. His next step was to track down other personnel stationed at the fort during the war, and he located Dr. H. George Mandel, a professor of pharmacology at George Washington Medical School.

“We talked with him, and he began to tell us some really phenomenal stories about what he had done,” Bies says. “We also noticed that he has a German-Jewish background similar to Fred Michel and many of the other interrogators who served at Fort Hunt.”

Since speaking to Michel and Mandel, Bies and his colleagues have contacted more than 50 veterans who served at the secretive P.O. Box 1142 installation.

“Just getting to know these folks has been a hugely rewarding experience,” Bies says. “These interviews were very highly emotional for them, because they were German immigrants who, because of their status, could not enlist but could be drafted.”

It was this cultural background, including having been raised in some of the same cities as their prisoners, that allowed the interrogators to put their interview subjects at ease and enabled them to get valuable pieces of information, Bies says.

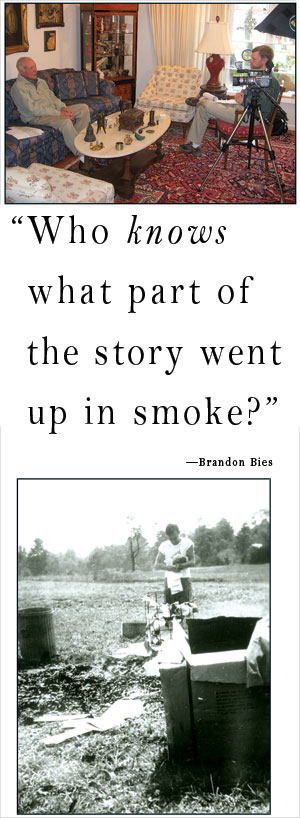

“Many of these American soldiers were from Germany and had lost family members during the Holocaust at places like Dachau and Buchenwald. For them, it was a very powerful emotional experience to learn later the important role they had played in World War II,” he says. Bies says that all the fascinating stories the fort’s veterans are sharing have provided a valuable lesson, especially because most of the documents from the project have been destroyed. “When the last veteran dies, there will be no going back,” he says. “We are only going to have the chance to do this work for a few more years.”

And, he says, the veterans themselves view the experience of talking about what happened at Fort Hunt as a way to save a piece of history that otherwise might have remained unknown.

“These soldiers did not have a chance to tell their story to others before this experience. They did not get to have reunions, there were no parades, and when they left the service, there was no one to say thank you.” Bies says. “It is wonderful to know that we have made a difference—that we have been able to tell them how much we appreciate what they did.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes, AS ’04