Peering into cell structures where neurodiseases emerge

Magic-angle-spinning NMR used to probe protein/microtubule assembly at atomic scale

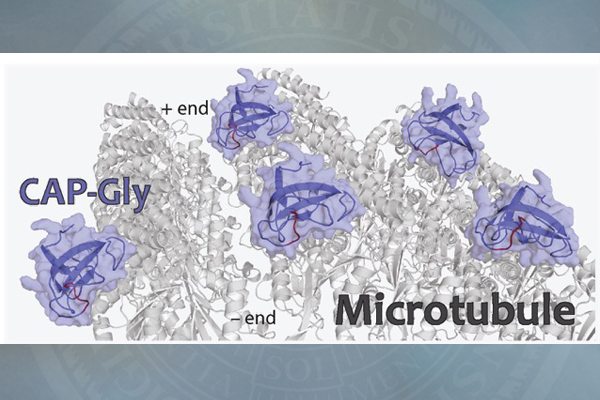

5:30 p.m., Nov. 24, 2015--A latticework of tiny tubes called microtubules gives your cells their shape and also acts like a railroad track that essential proteins travel on. But if there is a glitch in the connection between train and track, diseases can occur.

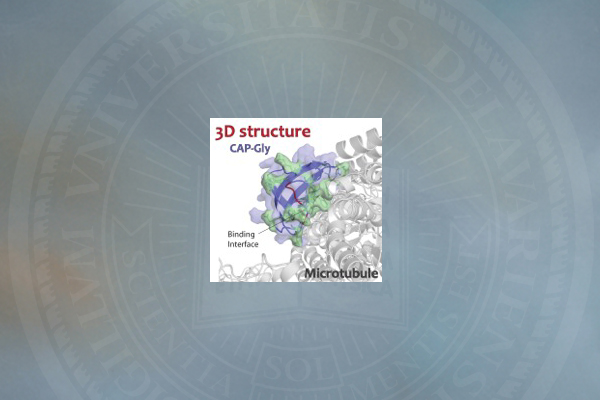

In the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Tatyana Polenova, professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and her team at the University of Delaware, together with John C. Williams, associate professor at the Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope in Duarte, California, reveal for the first time — atom by atom — the structure of one of these proteins bound to a microtubule.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

The protein of focus, CAP-Gly, short for “cytoskeleton-associated protein-glycine-rich domains,” is a component of dynactin, which binds with the motor protein dynein to move cargoes of essential proteins along the microtubule tracks. Mutations in CAP-Gly have been linked to such neurological diseases and disorders as Perry syndrome and distal spinal bulbar muscular dystrophy.

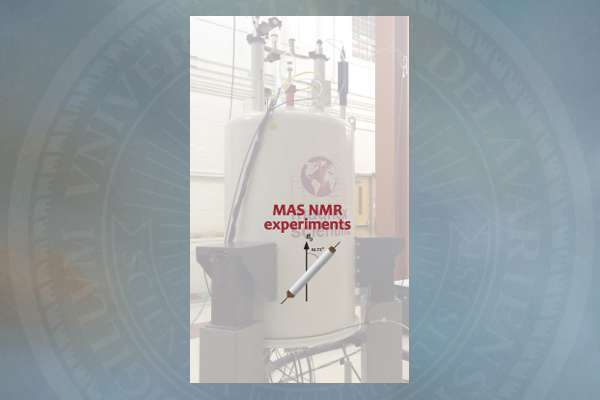

The research team used magic-angle-spinning nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry (NMR) in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UD to unveil the structure of the CAP-Gly protein assembled on polymerized microtubules. The CAP-Gly protein has 1,329 atoms, and each tubulin dimer, which is a building block for microtubules, has nearly 14,000 atoms.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to get an atomic-resolution structure of any microtubule-associated protein assembled on polymerized microtubules,” Polenova says. “With magic-angle-spinning NMR, we can look into the structure of this and other assemblies of microtubules and their associated proteins and gain critical insights into their function and dynamics, as well as begin to gather clues as to how mutations cause disease.”

In this technique, a sample is placed in the NMR’s small, tube-like rotor, which is then spun inside the NMR magnet at an angle of 54.74 degrees — called the “magic angle” because it suppresses the atoms from interacting magnetically.

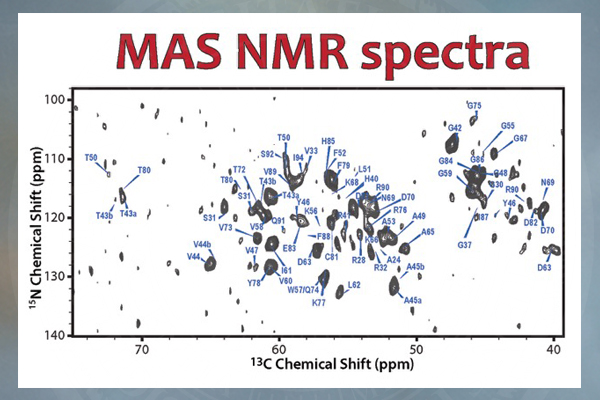

The result is a high-resolution protein fingerprint, a graph of hundreds of peaks representing the frequencies of two or more interacting atoms. These data are then used to calculate the 3-D structures.

The 3-D structures of CAP-Gly, which show the spatial arrangement of atoms in the protein molecule, are different between the free state of the protein and its bound state to the microtubule. These structures reveal how the protein interacts with microtubules, predominantly through its loop regions, which adopt specific conformations upon binding.

However, static structures of CAP-Gly do not tell the whole story about the protein.

“Just as we are always moving our arms and legs about, proteins are very dynamic. They do not stand still,” Polenova says. “These motions are essential to their biological function, and NMR spectroscopy is the only technique that can record such movements, with atomic resolution, on a variety of time scales, from picoseconds to arbitrarily long time scales — seconds, days, weeks — to help us understand the protein’s function. We know from our prior studies that CAP-Gly is dynamic on timescales from nano- to milliseconds, and this mobility is essential for the protein’s ability to interact with microtubules and with multiple other binding partners.”

The research, which has been ongoing since 2008 when the first data sets were collected, required the development of new protocols for preparing the samples, new NMR experiments to gather various information on structure and dynamics, and new protocols for data analysis.

In the future, Polenova and her team envision using NMR in combination with cryo-electron microscopy, in which samples are studied at extremely low temperatures, typically below 200 degrees Fahrenheit, to look at even more complex systems in a highly preserved form.

Polenova’s research team at UD included Si Yan, who received her doctorate from the University in 2014, current doctoral student Changmiao Guo, NMR spectroscopist Guangjin Hou and postdoctoral researchers Huilan Zhang and Xingyu Lu. Williams, at Beckman Research Institute, also was a co-author of the study.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The National Science Foundation funded one of the NMR spectrometers used in the research.

Polenova and her students and colleagues published a second article, on protein regulation of HIV activity, in the same issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Read that UDaily article here.

Article by Tracey Bryant

Photos by Evan Krape

Scientific figures by Polenova Lab/University of Delaware