New view of 'untouchables'

Research revises old assumptions about group's history and society

11:24 a.m., Sept. 29, 2011--When a Dalit political party achieved unprecedented electoral success over the last two decades in northern India—even generating talk about its leader becoming the nation's prime minister someday—Ramnarayan Rawat wondered how a group once considered "untouchable" had gained such power.

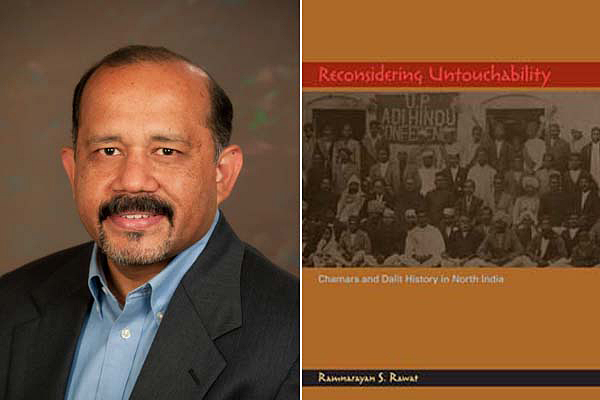

In researching the subject, Rawat, an assistant professor of history at the University of Delaware, discovered that much of what had been assumed about the Dalit society and history was not entirely accurate. His book Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India (Indiana University Press) has been described as "path-breaking" and "revisionist" and won the Joseph W. Elder Prize in the Indian Social Sciences from the American Institute of Indian Studies.

Global Stories

Fulbright awards

Peace Corps plans

"Mainstream scholars and journalists have found it difficult to explain how this important political party developed and how Mayawati [chief minister of the Uttar Pradesh state in northern India, who was first elected in 1993] became the first Dalit to rise to such a position of political leadership," Rawat said. "My book provides a history that traces the development of Dalit political consciousness in the 20th century."

The book examines the long-held belief that the Dalit groups, such as Chamars in the northern part of the country, were labeled untouchable under Hindu religious and theological beliefs because they worked with leather or other occupations considered unclean by religious Hindus. Instead, Rawat said, historical records show that the majority of Dalits have been peasants and farmers, often for many generations. He also found that this group has had a long history of political struggles and involvement.

Today, Dalits constitute 170 million, or 17 percent, of India's population. They make up nearly 22 percent of the population of Uttar Pradesh, and Chamars are more than half of this group.

After India gained independence in 1947, its constitution abolished discrimination against untouchables, but Dalits are still stigmatized in some parts of the country, Rawat said. In urban areas, he said, Dalits aren't visible as a particular group, but in some rural areas, they still live in separate villages and so are readily recognized as untouchable.

However, thanks to the legal system and a policy of affirmative action in government employment, Dalits today are often educated, socially mobile and have their own distinctive middle class, Rawat said, adding that marriages between castes also are now common.

"It has changed, and it's still changing," he said. "And that is the power of democracy—the beauty of democracy—that people can, through political action, really change things."

Rawat's next book project examines Dalit political and cultural struggles and their relationship with the evolution of Indian democratic practices in the 20th century. In particular, he is exploring the practice of counter-demonstrations by Dalit organizations beginning in 1922, the role of Dalit-owned printing presses, the role of Dalit schools and hostels and the role of Dalit public schoolteachers.

In conducting his research, which has included interviews with Dalit families who have shared personal records and photographs with him, he learned that such involvement dates back to the 1920s, when political demonstrations and counter-demonstrations often involved Dalits.

As a group, they also began establishing schools and urging families to educate their children. "It became a political act," Rawat said. "The message was: Send your kids to school so they can move out of untouchability."

At the same time, he said, Dalits took jobs as schoolteachers, often using that role to become more educated themselves and to become community leaders and, eventually, political leaders.

Rawat joined the UD faculty in 2010 after teaching at the University of Notre Dame and then holding a Mellon postdoctoral teaching fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania. At UD, he became the first specialist in Indian history, enhancing the history department's Asian section.

Article by Ann Manser