Hubba-Hubble

Hubble Telescope to help UD astronomer research white dwarf stars

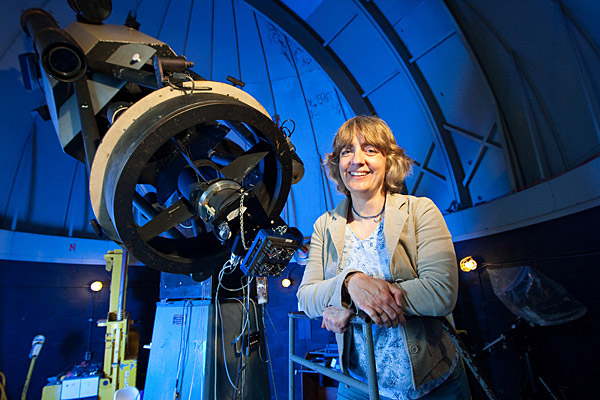

9:49 a.m., June 21, 2012--NASA has awarded University of Delaware astronomy professor Judi Provencal research time on the Hubble Space Telescope, and, as you might imagine, Provencal is over the moon about it.

“The telescope is so oversubscribed it is an honor to be awarded time to use it,” says Provencal, who is an assistant professor in UD's Department of Physics and Astronomy and director of the Delaware Asteroseismic Research Center (DARC).

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

According to James Green, NASA’s director of planetary science, the oversubscription rate for the current proposal cycle was six to one. Provencal’s was among those top-ranked for scientific merit.

Since its launch in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope has been floating in Earth’s orbit at an altitude of about 353 miles, capturing light on its nearly eight-foot-diameter mirror and directing that light to its scientific instruments, including advanced cameras, spectrographs that separate the light waves into frequencies for further analysis, and a spectrometer or heat sensor.

The Hubble has produced some of the most striking images ever recorded of cosmic phenomena, and it has helped reveal some of the deepest mysteries of the universe, ranging from the universe’s age (13 to 14 billion years), to the existence of dark energy, the mysterious force causing the universe to expand.

Unlike a telescope on the ground where observing time is granted in units of “nights,” Hubble’s time is granted in “orbits.” The telescope orbits Earth every 97 minutes at an altitude of about 353 miles, passing into Earth’s shadow for about a half hour each orbit.

Provencal will have 16 orbits on the Hubble telescope and six stars to observe -- all dying stars called white dwarfs, with helium atmospheres.

“We’re trying to determine their temperatures,” Provencal says. “This can’t be done with any accuracy from the ground, so we rely on Hubble to see ultraviolet light -- the shorter wavelength photons associated with high energy.”

Provencal won’t be allowed to actually “drive” the telescope, but she will work closely with staff at the Space Telescope Science Institute, the 400-person organization responsible for research done on Hubble, to create a detailed schedule of exactly what to do for each target as each star has a different amount of time when it is available for observations since Earth gets in the way for part of the time.

One of Provencal’s targets, KIC8626021, also is being observed by the Kepler satellite, which is staring at 150,000 stars near the constellation Cygnus, looking to find planets as they pass between Earth and the sun, called a “transit.” The Venus transit occurred a few weeks ago. KIC8626021 is the only helium atmosphere white dwarf within Kepler’s field that is “pulsating,” or changing its brightness. Kepler will be observing those changes in brightness for the next two years.

“Once we have an accurate temperature for this star using Hubble, we will be able to use the pulsation frequencies -- which will be the most accurate ever for a white dwarf -- to understand the star’s internal composition. We will also be able to tell how fast it is rotating, and whether it has a magnetic field,” Provencal says.

She notes that these observations also tie in to her work with the Whole Earth Telescope, a global program that involves ground-based telescopes, much like an Olympic relay team across the world’s time zones, to gather data that reveal the pulsation frequencies of particular dying stars.

“The accurate temperatures from the Hubble Space Telescope will help us better use this information to improve our understanding of the internal composition and structure of stars, as well as how energy is transported through their atmospheres,” Provencal says.

“The sun will become a white dwarf in a few billion years,” she notes. “These dying stars tell us about previous generations of stars and so give us the history of the Milky Way Galaxy.”

Article by Tracey Bryant