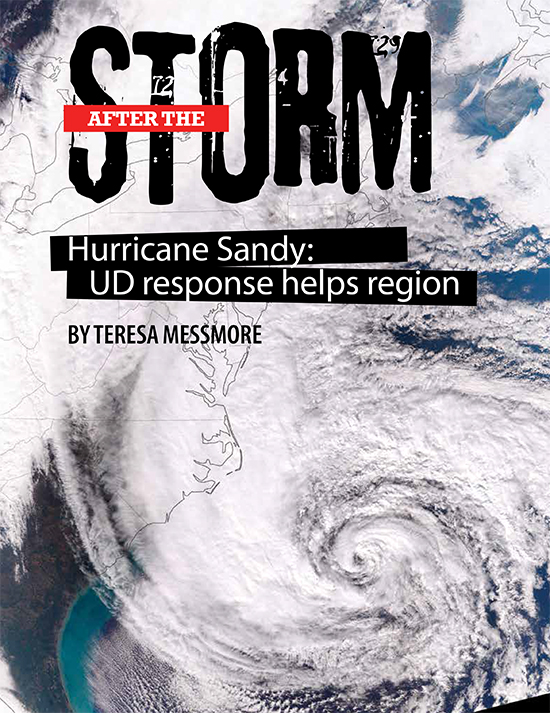

Hurricane Sandy was the deadliest and most destructive hurricane of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season. It ranks as the second-costliest hurricane to hit the U.S. since 1900, the year when such reporting began.

When Hurricane Sandy targeted Delaware last fall, scientists in UD's College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment (CEOE) tracked the storm's path, scrutinized its environmental impacts and considered implications for the future. Their quick responses and ongoing analyses help keep the region prepared for natural hazards.

As the massive storm approached, the Office of the Delaware State Climatologist and the Delaware Geological Survey provided emergency responders with up-to-date weather information. They pulled data from satellite receiving stations on campus, as well as a statewide monitoring system that aggregates measurements like rainfall and wind speed online.

Once the storm passed, they used hundreds of satellite images to make a computer animation that showed Hurricane Sandy's dramatic development. They also looked for trends among the nearly 200 such tropical cyclones that have touched Delaware since 1851, finding that the storms most often hit in September and arrive from the Caribbean—although the most powerful ones tend to originate in the open ocean.

Fellow CEOE scientists Xiao-Hai Yan and Matthew Oliver used UD's satellite data to follow raw sewage entering coastal waters off New Jersey. Malfunctioning wastewater treatment plants generated the sludge, and the researchers looked at temperature and color variations on satellite maps to trace where the waste-water was headed and to keep municipalities informed.

Other scientists ventured out into the field to collect valuable data relevant to their work. Luc Claessens, a geography faculty member who studies human impacts on watersheds, dashed out in the rain just before and after the storm to see how runoff was pouring into White Clay Creek. Areas near UD's Laird Campus are known to have runoff issues, where stormwater from parking lots carves deep gullies into the ground and flushes sediment and nutrients into the creek. Hurricane Sandy's heavy rainfall created mocha-colored plumes of mud, and Claessens' water samples showed high levels of nutrients and sediment that can pose problems for aquatic life. Claessens is working to address these issues through green stormwater infrastructure and plans to expand his study throughout the Delaware Bay watershed.

Oceanographers Arthur Trembanis and Douglas Miller also looked at sediment changes caused by Sandy, but instead examined the sandy bottom of the ocean off Delaware's coast. They used sonar and an underwater robot to map the seafloor at a site 16 miles offshore before and after the storm hit to study the fingerprint left by 20-foot waves and strong winds. As they aim to better understand these environmental processes, their research also has potential military applications: Shifting underwater sands and sediment can bury and uncover explosives, so knowing how weather conditions affect such objects could assist the Navy.

Hurricane Sandy altered water properties in Delaware Bay, from sediment churned up by waves to dips in water temperature. William Ullman, professor of oceanography and geological sciences, and postdoctoral research associate Yoana Voynova studied those kinds of impacts on the bay and its tributaries. They collected data from Kent County's Land Ocean Biogeochemical Observatory, which they maintain, and monitoring stations managed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They found that water temperature and chlorophyll levels decreased as salt content and turbidity, or water murkiness, increased. The surge associated with the storm also significantly affected water circulation patterns in tributary branches of the bay. The researchers are trying to better understand what to monitor during future storms and how to interpret these data.

At Delaware Sea Grant, which supports research, education and outreach serving the state's coast, staff took a big-picture approach and documented Sandy's impact in southern Delaware through photos and video. Sea Grant's Wendy Carey and Chris Petrone used a time-lapse camera to capture inundation at a flood-prone road in Lewes, showing how a full moon and Hurricane Sandy combined to make for intense flooding. Carey also took photos in the field to record damage to Delaware beaches and bays. The material is now available for use in workshops and educational programs to demonstrate the results of storms and coastal flooding—both today and for the future.