OUR FACULTY | Over the past century or so, disposable goods have become increasingly pervasive servants to our time-pressed lives, satisfying society’s craving for low-cost convenience so inconspicuously that we pay little attention to their existence, or toss them without fanfare when usefulness fades.

History Prof. Katherine “Kasey” Grier wants us to think about our throwaway-enamored existence. To see our expendable goods not just for what they do and how they serve, but to consider what these items say about us all—about the society we have shaped, the businesses we have built and the ways in which “value” and “usefulness” shift along the continuum of cultural change.

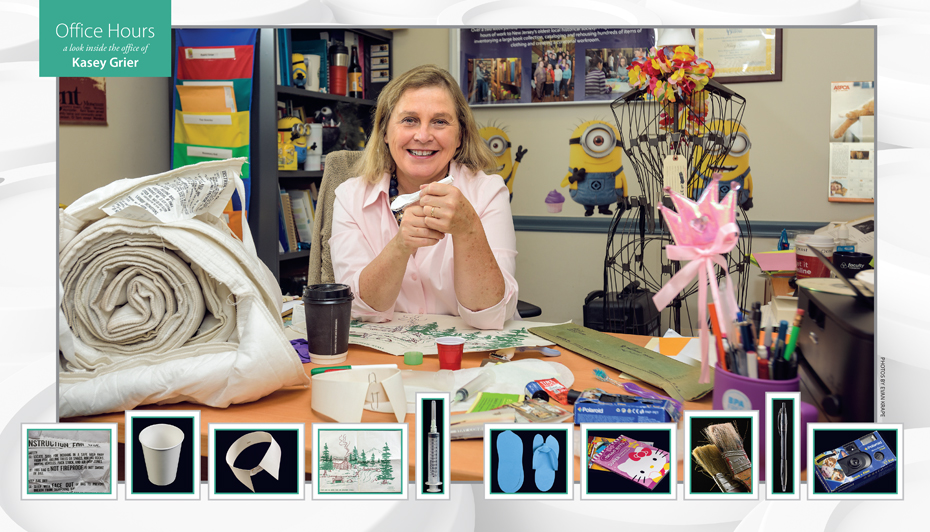

So for the past few years, this affable scholar of material culture studies and her team of graduate students have worked patiently to unravel the multicolored threads of our “disposable culture,” weaving tales that tie in an array of scholarly perspectives on our evolving civilization, from history and anthropology to psychology and economics. The results of their studies reside in Grier’s digitally housed “Museum of Disposability” (www.DisposableAmerica.org), filled with the ephemera of temporary utility, ranging from the everyday (plastic water bottles), to the anachronistic (disposable collars), to the odd (throwaway sleeping bags).

“These objects have the ability to teach, especially when you ask, ‘Why were they created?’” she says. “Information about our world—our ideas and ideals, our values, our economy and our technologies—are embedded within each of these items. They seem inconsequential, and can even be invisible to us, but in many ways, they show how the world works.”

Take the humble paper drinking cup. Within each is a tale of a time when people commonly shared the metal cups dangling at public fountains, oblivious to the threat of infection.

With the discovery of germ-borne diseases, a new business was born, and its commercial reverberations would soon spread, even helping to fuel the rise of fast-food restaurants decades later.

But just as the items can tell a tale of beneficial change, they also can speak to the impulses of greed, and the sometimes-damaging shifts of economic “progress.” Those same sanitary paper cups were initially coated with wax, and potentially reusable, until manufacturers realized more profit was possible if they removed the wax and made the cups prone to collapsing. And the demise of durable toothbrushes—originally made by home-based craftspeople of animal bone and boar bristle—also meant the end of many homemakers’ side jobs.

In the world of disposability, researchers also see implications about our very nature as consumers, and our vulnerability to the marketing-driven mindset that even perfectly serviceable goods must pass quickly and inevitably into obsolescence—to the detriment of both our planet and pocketbooks. Material culture researchers lament this “lost relationship” with objects that once were cherished, and wonder if it has really left us better off.

Looking ahead, Grier sees society’s infatuation with disposability rising, despite our modern embrace of ecological mindsets, giving her and her graduate students an ever-bountiful field of research. She’s already working to expand the website, and is developing K-12 lesson plans focusing on the issue.

“At first, this was just a little grassroots program, but it seems to have legs,” she says. “I almost feel it has an awakening impact on people. They look at the environment in a different way, they look at objects in a different way, and they look at their own practices as consumers in a different way.”

by Eric Ruth, AS93