FACULTY BRIEFS

An archaeological revelation

Long buried by shifting sands and nearly forgotten to time, the ancient Red Sea port city of Berenike in Egypt is more than a research project for UD History Prof. Steven Sidebotham. It is his life's work.

Over the years, he has dug through the soil to uncover glints of its busy past—a pet cemetery, a Roman-era trash heap, precious gems and even a humble container of black peppercorns.

But nothing prepared him for his most amazing find—stone fragments containing inscriptions (right) that imply travelers from ancient Egypt had been there more than 1,500 years before the city’s supposed founding in the third century B.C.

“We assumed there was no more to be found there,” he says of the temple area where the fragments were uncovered. By indulging their instincts to keep digging, Sidebotham and his team won Luxor Times Magazine’s “Top 10 Discoveries of 2015” (announced this February) for forever changing assumptions about the site that was a prominent stopover for so many ancient people.

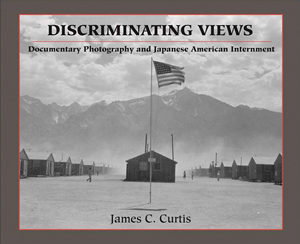

Pictures of deceit

At their best, pictures can tell a story. In James C. Curtis’ view, they can also lie, cheat and deceive.

The professor emeritus of history at UD has spent the last 50 years observing how so-called “documentary” photographs often veer from their supposedly impartial perspectives on the world, becoming a tool for propaganda and a betrayer of the truth they claim to embrace.

His latest excursion into this subtly skewed perspective takes him to the internment camps of World War II, where tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans were held against their will—their citizenship ignored, their allegiances doubted and their lives forever disrupted.

In his new book, Discriminating Views, Curtis aims to show how photographers slyly championed that agenda of disempowerment and racism through the scenes they shot and the captions they wrote. In photo after photo, the internees were referred to not as “Japanese-Americans,” but “persons of Japanese ancestry.” Rather than portray the gritty reality of the internees’ new lives in flimsy desert huts, the photographers carefully framed shots to give a false sense of contentment, pointedly excluding the realities of food shortages and deplorable conditions.

"These are wonderful photographs, but when these photographers say they had no preconceptions before they went in and shot a picture, that just doesn’t ring true for me,” says Curtis, former director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at UD. “You could say it was a different time. But you could also say it’s been a consistent theme since the 1930s in this country.”

It’s a theme with a lingering presence, Curtis believes.

“When I hear modern-day people arguing that there ought to be some kind of confinement of Muslims reminiscent of the Japanese internment camps, I’m outraged,” he says. “I hope history doesn’t repeat itself.”

In sleep, clues to health

The adage might well be true: Early-to-bed, early-to-rise sleepers tend to lead healthier lives (wealthier and wiser TBD).

In a study that uncovered bedtime routines of 439,933 people, UD researcher Freda Patterson and collaborators discovered that many of the habits that raise the risk of heart disease—smoking, sedentary lifestyles, poor diet—were far more prevalent among people who sleep too little, too much or get to bed too late.

While the cause-and-effect connections between sleep habits and unhealthy lifestyles remain uncertain, Patterson’s findings are raising hope that it might be possible to lead people toward more beneficial behaviors simply by getting them to adopt different bedtime routines.

The impact could literally save lives: Low levels of physical activity, poor dietary intake and tobacco use are blamed in 40 percent of all cardiovascular deaths in the United States and United Kingdom.

Patterson says the study—conducted with colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University and the University of Arizona College of Medicine—was the first to link heart-unhealthy habits with a tendency to be a “night owl,” and the first to find such markedly increased odds of being a smoker (36 percent) among people who sleep for nine or more hours.

“These data suggest that it’s not just sleep deprivation that relates to cardiovascular risk behaviors, but too much sleep can relate as well,” says Patterson, assistant professor of behavioral health and nutrition in the College of Health Sciences. “Oftentimes, health messages say we need to get more sleep, but this may be too simplistic. Going to bed earlier and getting adequate sleep was associated with better heart health behaviors.”

It’s clear to Patterson that the behavioral and physiological mechanisms that underlie her findings are complex, and in need of a deeper analysis. While a too-short sleep duration (less than six hours) is linked to a 45 percent increase in the odds of being a smoker, it’s also clear that nicotine’s effects as a stimulant may contribute to sleeplessness.

“There are some who believe that sleep as a physiological function is upstream to these heart-health behaviors,” Patterson says. “If that is true, the implication would be that if we can modify sleep as a central risk factor, we might be in much better position to leverage or modify some of our most stubborn cardiovascular risk behaviors such as tobacco use.”