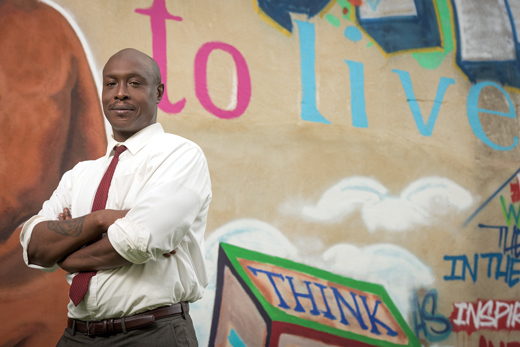

The Payne Prescription

OUR UD | What this man is saying will surely make people angry. It will make them uncomfortable. It may even inspire troubled and unwelcome thoughts of painful topics, of matters that might seem best left untouched and unresolved for another 350 years.

And that, Yasser Payne believes, is just what the people need. They need to be angry. They need to think. Because people are dying.

It has been a century and a half since the end of slavery, and still young black men’s lives are ending in violence. Still, poverty and despair seem to be a vise that grows ever tighter for countless masses who live in the richest nation on earth. Still, despite all that smart and earnest folk do or say, America cannot seem to finally realize its noble notion of “one nation, indivisible,” under God or anyone else.

So the talking heads and the learned men and the social media trolls alike endlessly wonder: What’s causing these troubles? How can we end them? And who is really to blame?

Here is where Yasser Arafat Payne, with his remarkably disparate first-person perspectives of poverty- and violence-plagued youth, rigorous academic training and street-smart science, may start to rile some sensibilities with the answers he has found and the prescriptions he has come to favor during his time as an associate professor of Black American Studies at UD.

Research methods, revolutionized

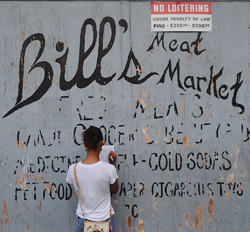

At first, this 40-year-old’s methodology for beginning to address poverty and violence in urban black communities may seem unusual. Through the Participatory Action Research (PAR) model, Payne sends teams of young men and women—some ex-offenders, all recruited from the Wilmington city streets that threatened to consume them—back into their communities, where they assess with rigorous honesty the people’s fears, dreams, hopes, terrors. House by house, story by story, they chart just how many in the community fail to graduate from school, how many fathers are missing, how many have ended up in jail. They gather the points of light needed to paint an unflinching picture of how people feel about things like policing policies, and just how much violence they see in a typical week.

By serving to document the condition of their communities, these men and women not only are helping legitimize residents’ struggles, they are undergoing an “intervention” themselves—diverting them from a dangerous path and potentially leading them to a place of pride, and setting them on their first steps toward a higher goal for themselves—possibly even toward the prize of higher education that has eluded so many around them. So far, several of Payne’s team members have gone on to college, and some are pursuing advanced degrees. “This is a re-entry program, in essence,” he says. “It’s also a social action program, to shake things up.”

Participating in PAR and working with Payne inspired 45-year-old Wilmington resident Darryl Chambers, AS14M, to push on for his master’s degree in criminology at UD, and today he is working toward his PhD. “I believe it was meeting Yasser in the PAR project that absolutely helped me out,” he says. “More important, what he did was he opened some doors for me,” ones that would lead to a graduate degree and a new outlook on the future.

“Prof. Payne is the reason why it works. Another professor could do PAR in the same manner as Dr. Payne, but another professor may not have the same ability to reach people within Wilmington the way that he does,” says Daroun Jamison, a community member who has worked with Payne. “It is his love and compassion for the people in the community that drives PAR. It is because he doesn’t see ‘us’ as ‘them’—he sees ‘us’ as ‘we.’”

Other academics have tried their versions of street ethnography, but Payne says his is the first to incorporate an element of rehabilitation for the surveyors themselves. So far, Payne’s model of surveys and accompanying programs has been tested in Wilmington’s most troubled neighborhoods, and is already spreading to other cities, in California and Massachusetts.

The People’s Report

The research and the report that followed Payne’s examination of Wilmington’s East Side and Southbridge neighborhoods in 2010—called The People’s Report—have grabbed news headlines and public attention.

Ultimately, by painting a truer portrait of poor black communities’ conditions and attitudes through a depth and breadth of survey data, Payne believes more people will begin to see why violence has become such an intractable part of these communities, and how its roots lie in an economic, legal and political system that remains biased in many respects.

The stories, feelings and fears of the people he and his team surveyed are summed up with academic precision in the report, which lays out personal despair with crisply powerful statistics: At the time of the study, 64 percent of Delaware’s prison population was black, and 50 percent of Wilmington’s black youth failed to graduate from high school. In the crime-plagued Wilmington neighborhoods of East Side and Southbridge, 70 percent of black men were jobless—and most were seeking work.

Among all residents, 70 percent reported “seeing someone else being threatened with physical harm” in their lives—56 percent reported seeing it in the last month. Half of the residents disagreed with the statement, “the police are here to protect me,” and 72 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “police respect me.”

The People’s Report has made Payne a hot ticket on the academic speaker circuit, especially for fostering “re-entry” of convicts and putting community-action on the ground. It has even led to requests for Payne to run sensitivity training sessions for cops and social workers. “There are people around the world who are paying attention,” he says.

But, in Payne’s mind, all of it does nothing if it does not get to the point where similar projects are being done in poor communities across the country, so that a larger, more powerful portrait of poor black peoples’ true plight emerges.

“If we can do that, it will have a tidal wave effect,” he says.

Structural violence

The power of Payne’s efforts lies in the seemingly impersonal data and statistics that serve to quantify the decidedly personal conditions of entire communities. It will be those numbers and statistics, he believes, that ultimately validate what for Payne is an inescapable conclusion: “We need to understand that this is a population that has been sustained in economic poverty for centuries.”

Just as it was 350 years ago—when black Americans couldn’t vote, or get a decent education, or even leave the state—the system is irreconcilably broken, Payne says. The nation’s legal and moral “accomplishments’’ in resolving racial inequity—constitutional amendments, Brown vs. Board and two Civil Right Acts 100 years apart—did not, cannot and will not break the cycle of poverty for the poor African-American subculture, because the system that purports to provide an opportunity to lift “any American” up and out of that condition is in reality designed expressly to keep that person down, “especially if that person is black,” he adds.

It’s simple accounting, in a way. Capitalism’s great churning machine of commerce needs a solid counterpoint of subjugation—always has, always will, Payne believes. “A capitalistic system requires poverty. It requires haves and have-nots. It requires losers,” he says, holding out a dollar bill. “The only thing that gives this any value is the fact that someone doesn’t have it.”

The “system” as it is also inevitably requires that people endure despair and hopelessness, Payne says. It requires broken families and hungry bellies. And ultimately, as naturally as the abused spouse one day lashes back, or the whipped dog bites, all of this leads to violence—violence against each other, violence against the “system,” violence turned inward and outward like a cancer, settling in like a unshakeable sickness.

Payne and others call it “structural violence,” and once in place, it feeds, and grows. Occasionally, it boils over in scalding fury—in places like Watts and Ferguson and Baltimore.

Payne’s views on structural violence—and especially his focus on its role as the primary cause of grief in black communities—is at odds with some. Scholars have historically seen poverty as correlating strongly with crime for all people, black and white. On the conservative side of the debate, the role of individual responsibility, behavioral choices and social structures simply must be factored into conversations about causes and solutions.

“Someone’s environment does not mean with absolute certainty they will turn out a certain way. Hundreds of people in those neighborhoods resist the temptations,” says Sen. Brian Pettyjohn, R-Georgetown, who has represented Delaware’s 19th District since 2012. “You’re not doomed to a life of violence and crime if you grew up in a neighborhood where violence and crime exist.”

And while he agrees with Payne’s contention that jobs will help bring out more opportunities, “It comes down to personal responsibility,” he adds.

In Payne’s world, such arguments underestimate the depth of the conditions, and the limitations of “personal choice” they impose. In many ways, The People’s Report is his most ardent rebuttal. For the hundreds who resist temptations and overcome a life of crime and violence, there are hundreds more who don’t.

Payne’s Rx

Ultimately, wholesale systemic overhaul is the only prescription to structural violence and poverty, Payne believes. But he isn’t content with accepting his own flat assessment. Problems that can’t be fixed short of social upheaval are nonetheless prone to poking and prodding, he knows. Already, The People’s Report has garnered attention in powerful places and won funding for more research, though Payne says more is needed.

And besides, as he learned so well on the streets: Just because a problem is bigger than you doesn’t mean you shouldn’t fight it.

So he works, and wrangles, and thinks—and when the injustices are too stark to bear, when he’s in the cockroach-infested home of a mother with no food for her hungry babies, he cries. But then it’s on to the next push forward: This summer, Payne put together a book that recast and re-emphasized The People’s Report and its conclusions. Maybe, if released simultaneously with a DVD documentary, more people will listen, and more people will hear, he hopes.

Down the road, he sees training manuals, and models for setting up street-survey and community action programs, making their way to the grim streets of so many cities. He has conducted presentations on his methodology to interested groups across the country and is consulting with California State University and Brandeis University on efforts in Los Angeles and Lawrence, Massachusetts, modeled after his program. He envisions bigger groups, broader efforts, possibly involving “hot -spot” teams focusing on stopping specific conflicts in neighborhoods the way a doctor would stop a disease. He sees the University of Delaware becoming a leading institution in the effort. “We could create a synergy the world would never forget.”

As far as real change goes, Payne knows it will take time. But he’s ready to wait—and work, and maybe help wriggle a few of his people out from under that 350-year-old boulder.

“We’re going to play long ball,” he says. “Time is on our side.”

Article by Eric Ruth, AS93

WEB EXTRA: For more on Payne’s PAR study, watch his TEDxWilmington talk at: http://www.udel.edu/002623