For chemists, no limits on career potential

ON THE GREEN | Chemists with disabilities are working in food and drug safety, conducting chemical education research, tutoring math and science, and teaching at universities across the country.

But Karl Booksh, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UD, knows that more needs to be done to prepare students with disabilities to become leaders in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

That’s why he created the Chemical Sciences Leadership Initiative, which brings eight to 10 undergraduates with disabilities from across the country to campus to gain practical experience as research assistants working with UD professors. The program is supported by the National Science Foundation through its REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) program.

“STEM graduate students with disabilities are a significantly underrepresented minority,” says Booksh, who navigates the halls of Brown Lab in a wheelchair. “Graduate school has become a critical juncture where STEM students with disabilities disproportionately abandon educational advancement.”

REU projects seek to broaden participation in science and engineering, particularly among underrepresented minorities.

Last summer, eight students with disabilities ranging from autism and visual impairments to deafness and developmental disorders joined Booksh, co-principal investigator Sharon Rozovsky and six other faculty members for an eight-week intensive research and education experience in various fields of chemistry.

The program included not only science but also practical advice on dealing with disabilities, requesting accommodations and completing grad school applications.

Josh McNeely, a junior at the University of Missouri, gained valuable experience using an array of high-tech chemical characterization equipment.

“This was an amazing opportunity for me,” says McNeely, who is blind in one eye and has Type I diabetes. “Because of my experience here at Delaware, I learned a variety of experimental techniques, and I’ve been offered a research appointment in bioengineering at my home institution.”

All the REU participants, along with scholars from a variety of other programs, presented their work at UD’s Undergraduate Research and Service Celebratory Symposium on campus in August.

For Nicole Tucker, who came all the way to Delaware from Oklahoma State University with her service dog, Ally, the symposium environment was challenging. Tucker, who has a form of autism, had to tune out the crowd and focus on presenting her work to interested attendees. But she says she welcomed the experience because she knows there will be other, similar situations in graduate school.

“We tend to focus so much on physical and sensory disabilities that we don’t think a lot about the range of other ‘hidden’ disabilities that can affect a person’s ability to be a chemist,” says Booksh, who is chair of the American Chemical Society’s Chemists with Disabilities group.

“Even mild disabilities can have a significant impact. Small hindrances can build over time to non-degree attainment. But if these students are given the opportunity and supported by role models, mentors and physical accommodations when needed, they can succeed.”

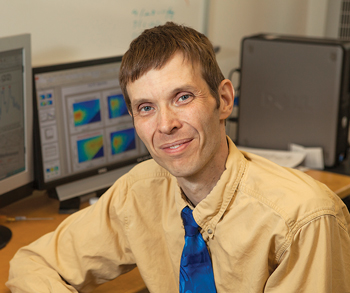

Graduate student Joe Smith, who served as teaching assistant for the program and mentored three student research projects, found himself deeply invested in how all the students’ work turned out.

“The whole progression for these students over the course of the summer is a beautiful thing to see,” Smith says. “We were able to show them that research really isn’t all that scary, and in turn they brought new energy to all of us here at UD.”

Article by Diane Kukich, AS73, 84M