Security overload may cause

employee cyber-stress

RESEARCH | From background checks and airport scanners to alarm systems and network firewalls, our lives are frequently touched by security mechanisms put in place to protect us. But can too much security actually cause us stress?

It’s a possibility, says new research by John D’Arcy, an assistant professor in UD’s Department of Accounting and Management Information Systems.

In a forthcoming Journal of Management Information Systems article, D’Arcy, with coauthors Tejaswini Herath of Brock University in Canada and Mindy K. Shoss of St. Louis University in Missouri, explores “security-related overload” and suggests possible ways to counter its stressful effects.

Here, D’Arcy discusses his research findings and the implications for future information security initiatives.

How can cybersecurity measures cause employees stress?

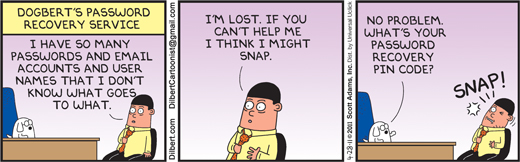

Employees are often given a variety of cybersecurity requirements in the form of policies, procedures and technical controls, and in particular, stress can result from overload, complexity and uncertainty. The result is that employees may engage in information security policy (ISP) violations. In this way, security requirements can actually backfire.

What are some of the ways employees engage in ISP violations?

Some examples of ISP violations include:

- • Failure to log off when leaving a PC or workstation;

- • Writing down a password;

- • Sharing a password; or

- • Copying confidential or sensitive data to a non-secure USB device.

Data leakage (for example, a human resources employee divulging salary information to someone outside the organization) is another major security compliance problem.

In many organizations, there are consequences for ISP violations. Can you explain why, when there are clear policies or procedures in place, employees will engage in such activity?

We found from the survey we conducted of over 500 employees who use computers on a regular basis that when security requirements are perceived as an overload, complex or uncertain, individuals can rationalize ISP violations. This rationalization process is called moral disengagement.

What are some examples of moral disengagement?

There are three general categories that such disengagement can fall into: reconstructing the conduct; obscuring or distorting consequences; and devaluing the target.

Employees may fall into the category of reconstructing the conduct if they employ “palliative comparison,” or considering a harmful act as acceptable by contrasting it with a more reprehensible behavior. Something like password sharing can fall into this category; an employee might argue that this ISP violation isn’t as bad as stealing company information. “Euphemistic labeling” also falls into this category; employees might see certain ISP violations as “no big deal” or an “inevitable reality” in the workplace.

In the distorting consequences category can fall the displacement of responsibility, in which an employee might deny responsibility for a violation due to perceived work overload.

Finally, in devaluing the target, an employee might blame others by attributing the violation to a strict or unreasonable policy.

So what’s the solution?

It’s important to note that it is the requirements of the policies, and not the security threats themselves, that can lead employees to engage in this behavior. If stressed employees are more likely to engage in these types of rationalizations that lead to noncompliance, then organizations need to rethink how they create information security policies.

Precise and clearly written policies devoid of jargon and technical terms can make security less complex, while periodic security training and education can eliminate uncertainty. Involving employees in the design and implementation of policies can also make efforts feel less intrusive and reduce negative behavior.

Article by Kathryn Meier, AS04, BE06M