Research briefs

Caught on camera: shrinking walrus habitat

Walrus use sea ice as a reproductive, migration and resting habitat. However, as sea ice melts and recedes, this marine mammal increasingly is threatened.

Now, a research team led by Chandra Kambhamettu, professor of computer and information sciences, has developed a novel camera system to map the surface topography of Arctic sea ice. The effort is part of a collaborative National Science Foundation project to assess walrus habitat.

Scott Sorensen, a doctoral student at UD, spent two months last fall aboard a German research vessel, where he installed three cameras to continuously capture images of the sea ice during the expedition. He and fellow doctoral student Rohith Kumar designed the camera system, and the team is now using the raw data to reconstruct polar ice floes in 3-D.

Walrus gather in large herds of up to 10,000 animals in the heavy ice of the central Bering Sea in winter. They move slowly on land, Sorensen says, and if the ice floes are too large, they are at risk for predators such as polar bears; too small, and the ice will not support the walrus’ weight.

Kambhamettu says the research could lead to a database of habitat and other information for use by other scientists and engineers.

National award recognizes composites work

Erik Thostenson’s fascination with composite materials grew out of his love for downhill skiing.

“I was intrigued that the performance characteristics of various skis could be remarkably different, yet the skis themselves could look identical,” he says. “The same basic materials—graphite, carbon and Kevlar—are used in most high-tech skis, but advanced composite technology enables mogul skis to be flexible while racing skis are stiff.”

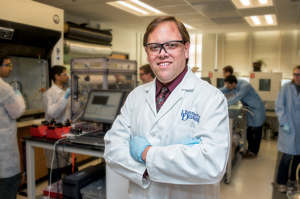

Two decades later, Thostenson is still fascinated with these high-tech materials and their applications far beyond performance skis. An assistant professor of mechanical engineering with a secondary appointment in materials science and engineering, he recently received a highly competitive Early Career Development award from the National Science Foundation to investigate a new processing approach for novel multi-scale hybrid composites with functionally graded material properties.

The research exploits the unique properties of carbon nanotubes, whose size offers opportunities while also presenting challenges.

“Because nanotubes are so small, they can penetrate the polymer-rich area between the fibers of individual yarn bundles as well as the spaces between the plies of a fiber composite,” says Thostenson, who also is affiliated with UD’s Center for Composite Materials. “The nanotubes become completely integrated into advanced fiber composite systems, adding functionality without altering the microstructure of the composite.”

Thostenson plans to study an environmentally friendly, water-based processing technique as an alternative to current energy-intensive approaches for integrating carbon nanotubes within fibrous structures. He also has developed a junior-level research and design project for his UD students and is planning a nanotechnology course module for high school students.

Article by Diane Kukich , AS73, 84M

Small change in ad might mean big money

Look at the two photos at right—how many differences do you see? If you answered just one (the placement of the logo), you are correct. And one is all marketers need to make you more likely to buy, according to new research by marketing Prof. Stewart Shapiro.

One change makes the same ad more memorable. Shapiro’s new study in the Journal of Consumer Research argues that by subtly changing an ad that appears many times, marketers increase the likelihood that consumers will remember the product.

“The question is, if you’re a marketer, should you always run the exact same print ad, or should they run slightly different versions of it?” Shapiro says.

If you’ve seen an ad before, it may be cataloged and stored somewhere in your brain, even if you don’t consciously realize it. When you see the same ad again, your brain recognizes it with little or no effort.

However, Shapiro says, if something changes slightly in the ad your brain needs to devote more energy to it. While you are likely not aware of the extra effort, it helps cement the ad in your mind.

Less pesticide in hive may help honeybees thrive

Deborah Delaney, assistant professor of entomology and wildlife ecology, has been studying 2 million research subjects—honeybees that make up UD’s 30-colony teaching apiary and research apiary. The latter apiary opened last summer at the University’s Newark Farm.

Delaney has received a grant from the federal Environmental Protection Agency for the project, which is being replicated at a new apiary at Penn State University. Research at both locations will focus on nonchemical ways to manage parasites in small colonies, with a goal of reducing pesticide use by small beekeepers by as much as 80 percent.

One possible way to do this, at least in small-scale beekeeping, is to disrupt the honeybees’ development by splitting a colony in two or by allowing the hives to swarm. Interrupting the cycle works especially well for Varroa mites, an ectoparasitic mite that is phonologically tied to honeybee development.

Historically, beekeepers have tried to prevent their bees from swarming because they thought the process was detrimental to honey production and pollination. But existing research already shows that colonies allowed to swarm show lower mite numbers and decreased bee mortality. Delaney’s research may help beekeepers look at apiaries as dynamic systems that require constant turnover.

“I’m trying to redefine what’s considered to be a healthy apiary,” she says.

Woodworking shop offers clues to the past

A group of trained professionals knew this discovery was equivalent to finding a needle in a haystack. Make that a needle kept in good condition, in a haystack the size of the United States.

After the discovery of an original 18th century woodworking shop on the site of a preschool in Duxbury, Mass., several experts in the material culture field traveled to see the find for themselves.

“The first time I saw it, I about fell over,” says Ritchie Garrison, professor of history and director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at UD. “It was a bit like walking into the past.”

Craftsmen, called joiners, used the workshop in the 18th century for skilled woodwork. Many of the original workbenches and structures are still fully intact and in remarkably good condition, Garrison says. He believes the shop could be one of the oldest in the country, especially if the date painted on the building—1789—is accurate.

“This is arguably one of the most important historical finds of my lifetime,” he says.

Superstorm Sandy scours the seafloor

Beneath the 20-foot waves that crested off Delaware’s coast during Hurricane Sandy last fall, thrashing waters were reshaping the floor of the ocean, churning up fine sand and digging deep ripples into the seabed. Fish, crustaceans and other marine life were blasted with sand as the storm sculpted new surfaces underwater.

UD scientists cued up their instruments to document the offshore conditions before, during and after Sandy’s arrival to analyze the differences and better predict the environmental impact of future storms.

“Out here, we’re trying to get the fingerprint of the storm,” Arthur Trembanis, associate professor of geological sciences and oceanography, said aboard the University’s research vessel Hugh R. Sharp.

Two days before Sandy hit, Trembanis’ group set up a specialized buoy with three different types of equipment attached that rested on the seafloor to measure waves, currents and sand formations on the seafloor. After the storm, the team used sonar equipment to find newly formed sand ripples, reshaped surfaces and exposed areas, with significant patches of “scouring” where erosion occurred due to rapidly flowing water.

Fabricating flexible, lightweight composites

Engineering researchers have reached a milestone in fabricating flexible composites based on carbon nanotube (CNT) fibers. The achievement was reported in the journal Advanced Functional Materials and was featured on the cover of the January issue.

Both light and strong, carbon nanotubes are known as a revolutionary material with excellent mechanical, electrical and thermal properties. Continuous CNT fibers are one-dimensional assemblies of the tiny tubes that belong to a new class of nano-structured materials with potential applications in electronics, sensing and conducting wires.

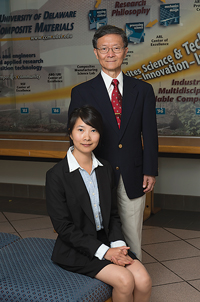

Motivated by their high electrical conductivity and ability to kink without cracking, Tsu-Wei Chou, Pierre S. du Pont Chair of Engineering, and his research team used CNT fibers to fabricate a stretchable conductor. The result was a flexible composite that can be subjected to repeated stretching-and-releasing cycles with little variation in electrical resistance.

According to the paper’s lead author, doctoral student Mei Zu, the findings demonstrate the potential of these flexible CNT fibers to be used as reinforcements for ultra-light weight multifunctional composites.

Defining the value of Luxury

A young woman in Tokyo pays 243,000 yen for a Louis Vuitton suitcase emblazoned with the company’s iconic monogram. A continent away, another woman purchases the same suitcase at the company’s store on New York’s Fifth Avenue for the equivalent U.S. price of $3,000.

What motivates their purchases? And do those motivations hinge on their location?

That is precisely what Jaehee Jung and her collaborators at universities in nine other countries sought to answer. Their findings, published recently in the journal Psychology and Marketing, compared consumers’ perceptions of luxury.

Despite the glum worldwide economy, luxury goods are selling well. Jung, an associate professor of fashion and apparel studies at UD, and the others found that consumers in different countries purchase luxury goods for different reasons.

In the U.S. it’s about hedonism. “American consumers generally buy goods for self-fulfillment, rather than to please others,” Jung says.

She surveyed American college students, many of whom responded positively to statements such as, “Pleasure is all that matters.” Factors including the quality of luxury items were not a driving concern for the students. Jung says this preference isn’t surprising; it is cultural.

“In Western cultures where individualism is valued there is generally less pressure to fit in with groups, such as peers and co-workers, than in Eastern cultures where collectivism is valued,” she says. Hedonistic tendencies may also be creeping into countries with developing economies—Brazilian and Indian students perceived luxury in the same way.

By contrast, surveys of students in France indicated that they value luxury items because they are expensive and exclusive, while Germans and Italians focus on function, placing emphasis on quality standards over prestige.

The researchers intend to keep exploring what drives luxury purchases, saying the findings have consequences for marketers as demand increases and their target consumer base widens.

Article by Andrea Boyle Tippett, AS02