Dover earthquake

Photo by Delaware Geological Survey December 05, 2017

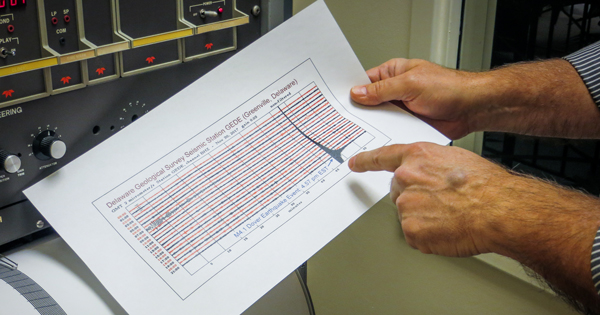

Delaware Geological Survey picks up first seismic wave from recent earthquake

Editor’s note: To share how you experienced the Nov. 30 earthquake, complete the DGS Earthquake Felt Report.

The earthquake that shook Dover, Delaware, on Nov. 30 began five miles below the earth’s surface and registered 4.1 on the Richter scale, a numerical scale that quantifies the intensity or magnitude of the event.

Delaware State Geologist David Wunsch said Thursday’s earthquake was the first to be felt in Delaware since August 2011, when a magnitude 5.8 earthquake struck central Virginia and subsequently reverberated through the First State.

Wunch directs the Delaware Geological Survey (DGS), a state agency housed in University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment. He said any earthquake in Delaware is surprising, but not concerning since the state is not classified as a highly active seismic zone. He shares why in the Q&A below.

Q: Why did the earthquake occur? Were there any warning signals?

Wunsch: Buried under Delaware are the same kinds of hard rocks that are visible in northern New Castle County, called Piedmont rocks. These Piedmont rocks extend underneath Delaware, buried under thousands of feet of sediment, and contain naturally occurring faults and fractures in them. As the Earth’s plates move around, it can create stresses, and occasionally these global stresses accumulate pressure that is released in the form of an earthquake. A colleague in Maryland reported small tremors measuring in Maryland last week, but we don’t know if there is any connection to the earthquake that occurred in Delaware Thursday.

Q: How did Delaware Geological Survey scientists confirm that an earthquake had occurred?

Wunsch: DGS operates a network of seismic stations in the state of Delaware to monitor earthquakes and feeds data into the Lamont Doherty Seismographic Network. These stations provide publically available, real-time data on seismic signals (or wave energy generated by earthquakes) that occur. The DGS seismic station located in Greenville in New Castle County was the first station to receive the seismic wave from Thursday’s earthquake. While the epicenter of the quake occurred about eight miles northeast of Dover, its effects were felt from Washington, D.C. to Yonkers, New York.

Q: Why did people in some areas of the state feel it and not others?

Wunsch: The hits of where people felt the quake runs in a line from Washington toward New York City, which isn’t surprising because this is where the Piedmont rocks in our area are situated. Piedmont rocks are dense, hard to erode rocks that tend to transmit earthquake energy more readily than flat, sandy sediments that you see as you head toward Delaware’s coastal beaches.

Q: Does Delaware have a fault line?

Wunsch: In any geologic system where rocks are buried beneath soil and sediments there will be faults. About 180 million years ago, the plate that includes present day Delaware split from an adjacent plate and created faults along the edges that are called rifts. Some ancient faults related to this rifting—most of which are inactive today--may exist beneath us. But Delaware does not have a major fault line, like the well-known San Andreas fault system in California. Instead, Delaware is located away from the edge of the North American Continental Plate, which is located a few thousand miles from Delaware in the Atlantic Ocean, placing the region at less risk for earthquake.

Q: How often do earthquakes occur in Delaware?

Wunsch: Fifty-eight earthquakes have been documented in Delaware since 1871, but it is only about every decade or so that there is an earthquake that people would feel (a magnitude 3.8 or more). To put that into perspective, approximately 3 million earthquakes occur worldwide each year, but ninety eight percent of them are less than a magnitude 3.

Thursday’s earthquake matched the previous largest event in Delaware, which occurred in 1871 and had an estimated magnitude 4.1. The largest recorded event in Delaware occurred in 1973 and had an estimated magnitude of 3.8.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website