School policing

September 22, 2016

UD’s Kupchik says policing, punishment in nation’s schools a serious problem

Aaron Kupchik, professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware, has spent the past decade studying how children are policed and punished in schools. His verdict? There is a real school safety problem in this country.

Schools, he says, are fundamentally undemocratic places where racial inequality is exacerbated and families suffer.

The number of police officers who now walk the beat in hallways lined with lockers has increased significantly. Earlier this month, the U.S. Department of Education released a set of tools to improve school climates.

The first recommendation: school discipline should be handled by trained educators, not law enforcement officers.

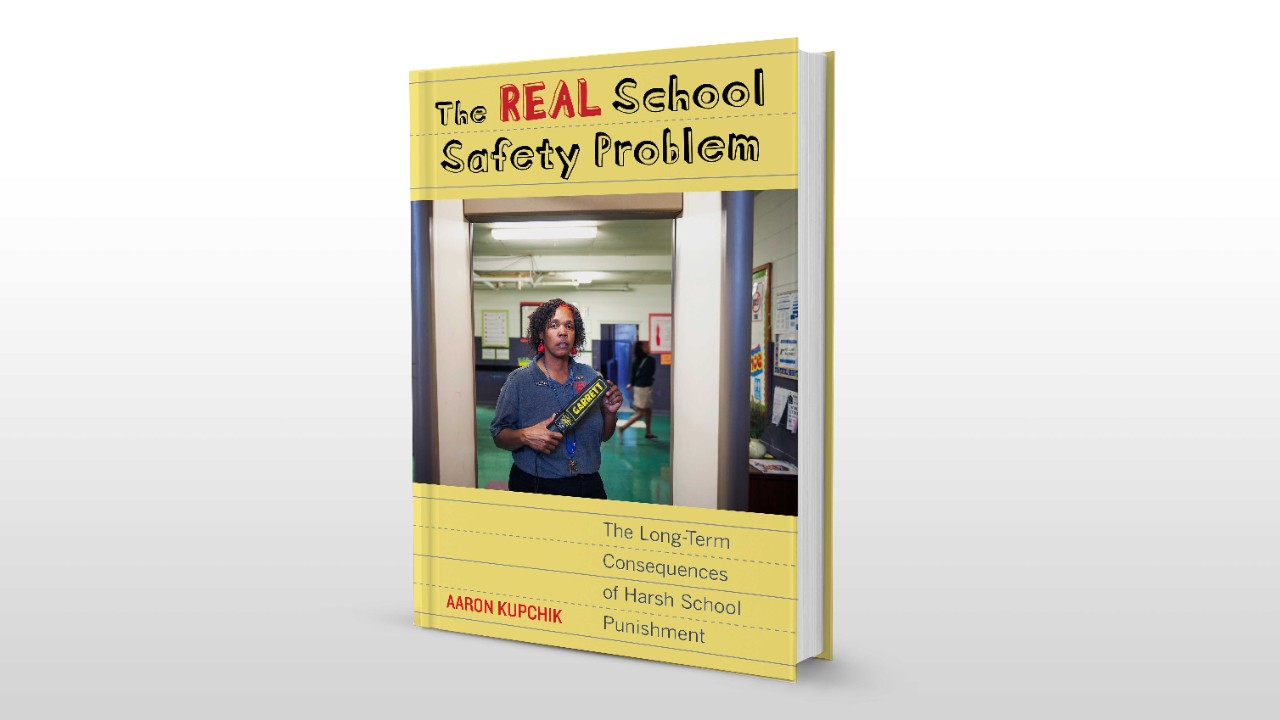

Kupchik, author of the book The Real School Safety Problem: The Long-Term Consequences of Harsh School Punishment, says that is incredibly important. He questions why police are in public schools and chatted with UDaily about alternative approaches.

Q: What is the real school safety problem?

Kupchik: The real school safety problem is the over-policing and over-punishment of kids.

Putting police officers in school is incredibly popular with almost every constituency. The problem is that putting more police officers in schools can have more negative consequences than benefits.

The presence of the police officer changes the environment of the school from one that is primarily focused on the academic, social and emotional needs of students to one that a bit more focused on law and order, enforcing laws and arresting suspects.

Q: What do you see as the negative consequences of school punishment?

Kupchik: The most important is that it increases racial inequality. Youth of color, particularly black youth, are much more likely to be suspended, expelled and arrested at school than are white youth, even when we control for their misbehavior. Among kids who commit similar types and numbers of misbehaviors, black youth are more likely to be suspended in particular, and this starts as early as preschool.

Most of these kids are getting punished for really minor offenses. We are not talking about violence or drug use. We are talking about talking back, disobedience against teachers, cursing in hallways, having cell phones, things that a generation ago would have just been handled by a principal or vice principal. Now kids get kicked out of school for it and it’s really problematic.

Not only is it a problem today, it’s a problem 10 years from now, 15 years from now. It’s a problem not just for those students. It’s a problem for communities. It’s a problem for families.

Q: Families?

Kupchik: Families of kids who get suspended tend to be low-income, they are more likely to be families of color, people who might be struggling to make ends meet to begin with, who then might have to take time off from work, risk getting fired. Many of the families we spoke to lost jobs or had their income effected.

It causes conflict within families. It causes the family to trust the school less. Sometimes it causes separation where the kid has to move in with relatives in order just to continue their education. It causes a lot of family suffering.

Q: You said it’s a problem for communities, too. What do you mean?

Kupchik: It really struck me how undemocratic the lessons that kids learned in schools were. Children are learning in schools how to interact with an authority, how to be citizens in a democracy. And the lessons that they learn through harsh punishment are undemocratic. So it makes sense years later that they would be apathetic if that is what they are being taught.

Years down the road in the future, kids are less likely to participate in civic society once they have been punished in schools in this way. Kids who get suspended are less likely to vote and volunteer years later.

Q: What connection does school discipline have to bullying?

Kupchik: In schools where students feel that the rules are unfair, there are higher bullying victimization rates.

It really struck me how much school discipline can look like bullying. We don’t think of it as bullying because it’s adults doing their job but it can be very mean, it’s targeted at the same kids repeatedly, it’s done intentionally to demean them. It’s an abuse of power at times. This is bullying just by a different name.

If kids go to school at a place where all the staff are smoking cigarettes, wouldn’t we expect a higher smoking rate in that school? When kids go to schools with less fair rules, we also see higher bullying victimization rates.

Q: What’s the solution to the “real school safety problem?”

Kupchik: We need to do less harm.

Restorative justice for example, in schools, where when there is a conflict, a child misbehaves or offends a teacher, damages property, acts out. There are consequences and they receive punishment but they do so without being kicked out of the community. They might have to do restitution or write letters of apology, but they learn about why what they did was wrong. They talk about why they did what they did and they learn better strategies. This has been shown effective in juvenile justice systems and in schools, yet too few schools use it.

Ideally we would have counselors, mental health workers in schools. There are reasons why children usually act out. Sometimes it’s because of trauma. Sometimes it’s because of what is happening at home. Sometimes it’s because they don’t understand what’s going on in class or are hungry. We need people who are willing, have the time to and are trained in how to look for those reasons and respond in ways that help solve problems not just remove them for three days.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website