Stereotypes and STEM

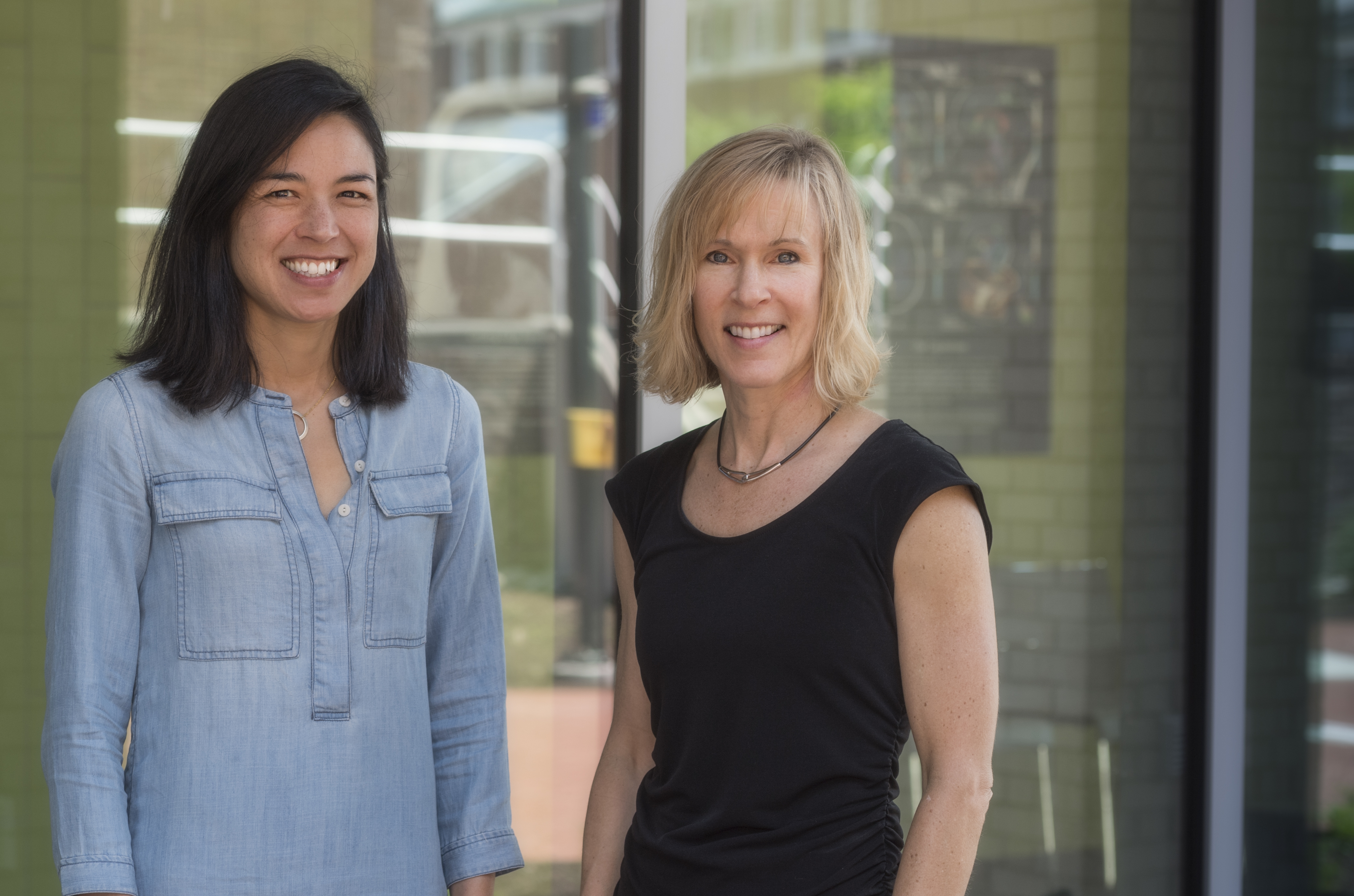

Research on problem-based learning, women's perceptions gets $1.8 million support

9:02 a.m., Oct. 29, 2015--As national attention focuses on the relative lack of women pursuing science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) studies and careers, a University of Delaware researcher is looking into a surprising potential culprit — the widely used teaching method known as problem-based learning, or PBL.

“PBL is popular in STEM domains, and there are a lot of studies that show it can be very effective,” said Chad Forbes, a social neuroscientist and assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at UD, who recently received a $1.8 million federal grant to study the issue. “But we also know that there’s this ‘leaky pipeline,’ with girls and women beginning to lose interest in STEM as early as middle school and continuing through high school and college.”

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

That decision by many women not to continue an earlier interest in STEM causes them to drop out of the “pipeline” that normally leads students from secondary school to college, graduate school and careers in a particular field.

Forbes has conducted previous research on “stereotype threat,” a term describing how, for example, women tend to do worse on math tests if they are reminded of their gender before taking the test. Psychology researchers believe this occurs because they are influenced by the stereotype that women aren’t good at math.

In addition, Forbes said, there’s a phenomenon known as “affective contagion,” in which someone’s emotional state influences others.

“This means that you sometimes ‘catch’ someone else’s emotional experiences,” he said. “If you’re in a good mood, and a friend who is unhappy or anxious starts talking to you, you may start to feel that way. And it can happen with strangers, too.”

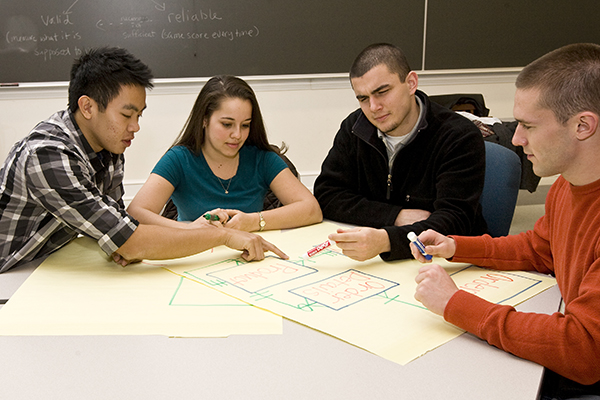

Because a hallmark of PBL involves students working in pairs or groups to solve real-world problems, Forbes got to thinking about what this might mean to women, especially in a class where they are far outnumbered by male students.

He wondered: Could the process of working in a predominantly male group cause a woman to experience stereotype threat, making her feel stress and anxiety and, possibly, unwittingly transmitting that to other female students? Women who experience those feelings of stress and anxiety could associate them with the STEM discipline itself and begin to avoid such classes.

“There’s clearly something insidious and subtle — it may not even be apparent — that goes on and influences women to leave STEM fields,” Forbes said. “There are societal factors that create negative stereotypes and influence women, but there are also individual factors, such as stress and anxiety and feeling bad about your own competence.

“Maybe PBL isn’t a factor, but there are ways in which it might be, and there really has been no research into this question.”

His research, conducted with colleague Tessa West of New York University, has already studied some stereotype-threat effects that occur when students are paired in a psychology lab and asked to work together on a math test. A woman under stereotype threat performs worse on the test when she works with a male student and better when she works with another woman.

But, Forbes said, the surprising finding was that the woman not under stereotype threat performed worse when paired with the stereotype-threat woman, who often asked her partner questions and sought her help. He believes that demonstrates that serving as a mentor is “cognitively taxing,” leaving the mentor less able to solve problems efficiently.

Do these findings mean that women should work only with other women in STEM classes and labs? Probably not, Forbes said. A lot of evidence suggests that girls and women respond well to all-female STEM classes, he said, but they eventually will have to work with men.

“There are a lot of other possible solutions” rather than gender-segregated classes, he said. “Just educating girls, letting them know about stereotype threat and what it means, might help them guard against it. That sounds basic, but it can make a difference.”

If PBL turns out to have negative effects on some female students, Forbes suggested that teachers could use that information to help organize their student teams in a way that minimizes the effect. For example, they could avoid putting a female student who is sensitive to stereotype threat on a team with a particularly assertive or negative male student.

About the grant

The National Science Foundation awarded the $1.8 million grant to Forbes, principal investigator, and West, co-principal investigator, through its Research on Gender in Science and Engineering program.

The research is estimated to take about four years, with the grant extending until about September 2019.

For the laboratory studies, looking at pairs of students working together to solve math problems, Forbes’ lab at UD focuses on the research participants’ brain patterns, while West at NYU focuses on their cardiovascular responses.

The researchers also plan to work with a group of students who have selected a high school STEM track at Newark (Delaware) Charter School. The school employs PBL in many of its classes, and Forbes said he hopes to follow the students over time — in their classrooms and in his lab — as they continue in STEM classes or decide to choose a different academic track.

Article by Ann Manser

Photo by Ambre Alexander Payne