First Year Common Reader

Author Stevenson urges commitment to compassionate justice and equality

12:47 p.m., Oct. 12, 2015--Bryan Stevenson, author and advocate for social justice, would like to see America move toward adopting a legal system based on fairness and compassion for those at all levels of the social-economic spectrum.

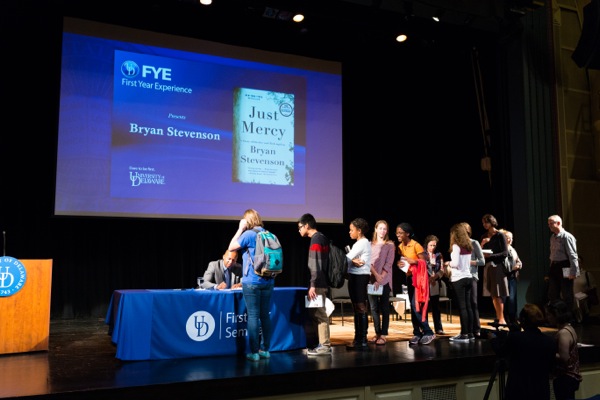

Stevenson, the author of Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, offered his message of hope and positive change during a University of Delaware First Year Common Reader Program talk, given Tuesday, Oct. 6, in Mitchell Hall.

Campus Stories

From graduates, faculty

Doctoral hooding

University Acting President Nancy Targett welcomed the audience of more than 650 students, plus an additional group watching remotely via simulcast in Kirkbride Hall.

Targett noted that each year incoming students are asked to read the same nonfiction book, and that past selections have included stories of loss, redemption and heartache.

“This year’s story is a very powerful story of race and bias, of justice and compassion,” Targett said. “It’s not light reading, but it is an important read because it helps us understand how the destructive narrative of racial difference permeates society and impacts all of us. Bryan Stevenson is truly an advocate for the humanity of people.”

Targett also introduced student moderators Monica Lindsay, a senior English and sociology major from the Bronx, New York, and Catherine Gamble, an organizational and community leadership senior with minors in public health and disability studies, from Howell, New Jersey.

Faculty moderator Carol Henderson, vice provost for diversity, introduced Stevenson, whom she described as an extraordinary human being.

“I believe it was Mark Twain who said, ‘the two most important days in an individual’s life are the day one is born and the day one finds out why,’” Henderson said. “We can all be grateful that Mr. Stevenson discovered why he was born and that he had the courage to step into that destiny, notwithstanding the cost.”

Stevenson, who was greeted with a warm Blue Hen welcome, recalled a previous visit to the UD campus and the impression that experience had on his life.

“I feel like I am back home. I am a proud native of the state of Delaware,” Stevenson said. “I was 16 years old when I came here to the campus of UD as part of an Upward Bound summer program. I wandered around the campus and got a taste and feel for what college might be like. It left an incredible impression on me.”

Founder and executive director of the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, Stevenson told the audience that not only is change needed, but that it is indeed possible to move America from a policy over-incarceration of its poorest citizens to a higher ground based on equal treatment and economic opportunity.

“I am persuaded that we can change the world. I really believe that we can do that,” Stevenson said. “I think that the people in this room have the capacity to create more justice for this country, and to create more fairness, more equality and more opportunity to do something about inequality, to do something about abuse and to do something about the lack of compassion. I’m persuaded that we can do it.”

Stevenson, who grew up in Milton, Delaware, said that over-incarceration and excessive punishment are huge problems that have to be addressed if positive change is to take place.

“As of 1972, we had 300,000 people in jails and prisons in this country, and today we have 2.3 million,” Stevenson said. “There are 6 million people on probation and parole, and there are 70 million Americans with criminal records, which means when they apply for a job or try to get a loan, they are going to be distinctly disqualified.”

The United States, Stevenson noted, has the highest rate of incarceration in the world, and the rate of women in prison here has increased more than 60 percent in the last 20 years.

“Seventy percent of these women are single parents who have children, and that means that when they go to prison, their children are going to be displaced,” Stevenson said. “We have all of these collateral consequences.”

Stevenson said that there often exists a sense of resignation and hopelessness among children in urban communities nationwide.

“Sometimes I sit down in low-income housing projects and have conversations with 12- and 13-year-old kids, and some of them tell me that they were marginalized and abused and disaffected,” Stevenson said. “They tell me that they don’t expect to be free or alive by the time they are 21. They believe that they or their siblings will be in prison by the time they are 21.”

To change the world and create more justice and more equality, people have to get closer to the problems that create and foster the current situation, Stevenson said.

“We have to first commit ourselves to the problems that we see around us,” Stevenson said. “You can’t create justice from a distance. When you are proximate, you see details you can’t see from a distance.”

Stevenson also said the narrative of fear and anger has to change.

“The problem of mass incarceration and excessive punishment is caused by the war on drugs,” Stevenson said. “We decided to declare drug addiction a crime issue rather than a health issue. This has put millions of people in jail. It is the narrative we have to change.”

Protecting one’s hope is important in keeping alive the belief that things can be changed, Stevenson said.

Getting close to the situation, changing the narrative and sustaining hope also means that people have to be willing to do uncomfortable things if they really want to change the world.

“I thought about why we want to crush broken people,” Stevenson said. “I don’t do what I do because I get paid to do it, I do it because I am broken, too, and there is something that understands the brokenness.”

Stevenson urged members of the audience to commit to changing the world and to not worry if the world looks askew at an individual’s commitment to social justice and equality.

“You honor yourself when you get proximate,” Stevenson said. “You create justice not only with the idea in your mind, but by the passion in your heart.”

Stevenson received standing ovations at the conclusion of his talk and after the question-and-answer portion of the program.

First Year Common Reader essay winners

Eight students were awarded prizes in the Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, essay contest sponsored by the First Year Experience program.

The winners, all freshmen, are:

• Amanda Goldstein, a music education major, from Plainview, New York, first place;

• Amanda Flores, a finance major, from Verona, New Jersey, second place; and

• Nehuen Aon Cortassa, an English education major, from Baltimore, Maryland, third place.

Honorable mention awards were presented to:

• Hannah Kimani, a University studies student, from Newark, Delaware;

• Benjamin Gillingham, an undeclared business major, from Northborough, Massachusetts;

• Rachel Schaefer, a civil engineering major, from Princeton Junction, New Jersey;

• Dana Mueger, a University studies student, from Greenlawn, New York; and

• George Thuku, a University studies student, from Middletown, Delaware.

About the First Year Common Reader

The First Year Common Reader is a unique opportunity for students to engage in a meaningful conversation with fellow students and to begin to share in the intellectual life of the entire UD community.

The book is read before arriving on campus, with speakers, films and other cultural events organized around the theme of the book throughout the first semester.

Previous common readers have included Thank You for Your Service, by David Finkel; My Beloved World, by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor; Behind the Beautiful Forevers: and Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity, by Katherine Boo.

For more information on the Common Reader, visit the website.

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Kevin Quinlan