Ancient water

Delaware Geological Survey carbon-dates groundwater found to be thousands of years old

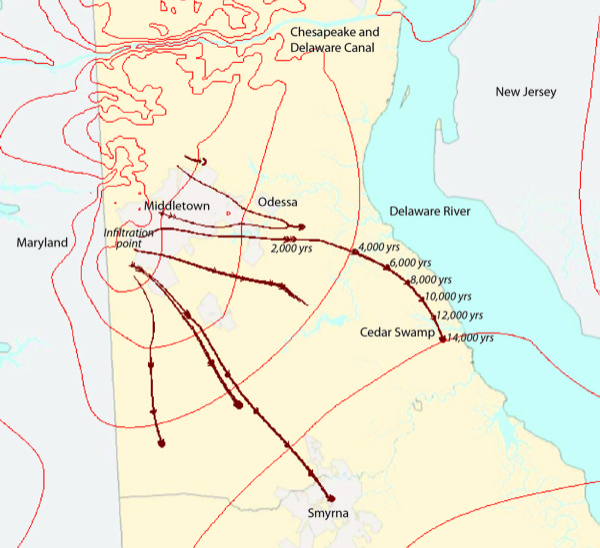

1:20 p.m., Oct. 31, 2013--A drop of rain that falls near Middletown, Del., may take as long as 14,000 years to seep through the earth and trickle underground into a well several miles away, according to new research by the Delaware Geological Survey (DGS).

Scientists used radiocarbon-dating techniques to determine the age of groundwater from sites in southern New Castle and Kent counties.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

“The ages were surprising to me,” said Scott Andres, senior scientist with DGS. “This water hasn’t seen the light of day for thousands of years.”

The findings may help refine estimates of groundwater replenishment rates and inform municipal decisions on where — and where not — to pull water from in the future.

With funding from the state, DGS is conducting a long-term groundwater study by monitoring wells at eight locations in the central Delaware. Groundwater is the only source of freshwater for potable and irrigation water supplies south of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal.

As part of the project, Andres and DGS colleagues Zack Coppa, Changming He and Tom McKenna are trying to better understand where water flows underground through areas of permeable sand, silt and rock called aquifers.

Based on the geology of the state, they can predict water’s subterranean routes using numerical models. Radiocarbon dating helps test the accuracy of those predictions.

The method uses the well-known decay rate of carbon-14, a common radioactive isotope of carbon, into carbon-12 to figure out the age of substances.

Radiocarbon dating has been used routinely in archeology and geology for decades to find the ages of archeological artifacts, soils and fossils. Use in water resources studies is becoming more common as costs have decreased and sampling and analytic techniques have improved.

While pure water is made of only hydrogen and oxygen, carbon from decaying plant matter in soil dissolves into water as it flows through the earth. That’s the carbon used in radiocarbon dating.

“In the case of groundwater, the carbon-14 age represents the time that the water was infiltrating through the soil zone — only taking a few months go through the soil — and then the amount of time needed for the water to flow from ground surface to the depth and location of sampling,” Andres said.

The scientists examined eight samples of groundwater from depths ranging from 160 to 520 feet, finding the samples to be between 6,500 and 16,200 years old. Rain falling at a site near Middletown, for example, was found to take an estimated 14,000 years to make its way 11 miles to a well situated not far from the Delaware River.

The new information will be used to update models of groundwater flow and consider the effects of pumping water out of wells. As the amount of water being pumped from the ground increases, and more deep wells are installed, changes occur in the aquifers that hold the water.

“Pumping reduces water pressure in the aquifer, causing groundwater-flow directions to change and flow toward the pumping wells,” Andres said. “These new tests show it is certain that deeper wells are pumping older water.”

As pumping lowers water pressure, pumps have to lift water up from greater depths, which will make the process consume more energy and be more expensive.

An additional planning consideration is that as water pressure declines near the coast, wells can start to pull in salty water. Samples collected from deep wells located east of Smyrna show elevated salt concentrations, one indication of how water use is affecting aquifers.

“Sampling over time will assist with calculating how long it takes for new water to replenish the aquifers, and how flow directions are changing in response to pumping,” Andres said. “This knowledge will allow DGS scientists to inform stakeholders about the economic benefits and environmental costs of water use.”

About the Delaware Geological Survey

DGS is a science-based, public service-driven state agency at the University of Delaware that conducts geologic and hydrologic research, service and exploration for the benefit of the citizens in the state. It is affiliated with UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment.

Article by Teresa Messmore

Photo by Teresa Messmore

Map courtesy of Scott Andres