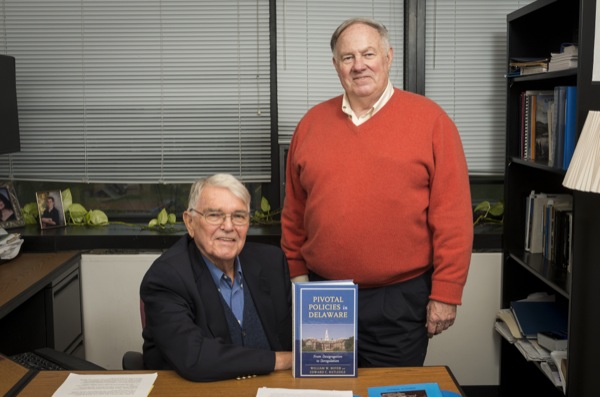

'Pivotal Policies'

New book looks at important public policy decisions in Delaware

9:25 a.m., Feb. 17, 2014--In their latest book, two University of Delaware authors report that the major drivers of public policy in the First State today are the federal and state judiciary, the governor and business leaders.

Previously, the state legislature had been the dominant force and its unquestioned power in making public policy lasted well into the second half of the last century.

People Stories

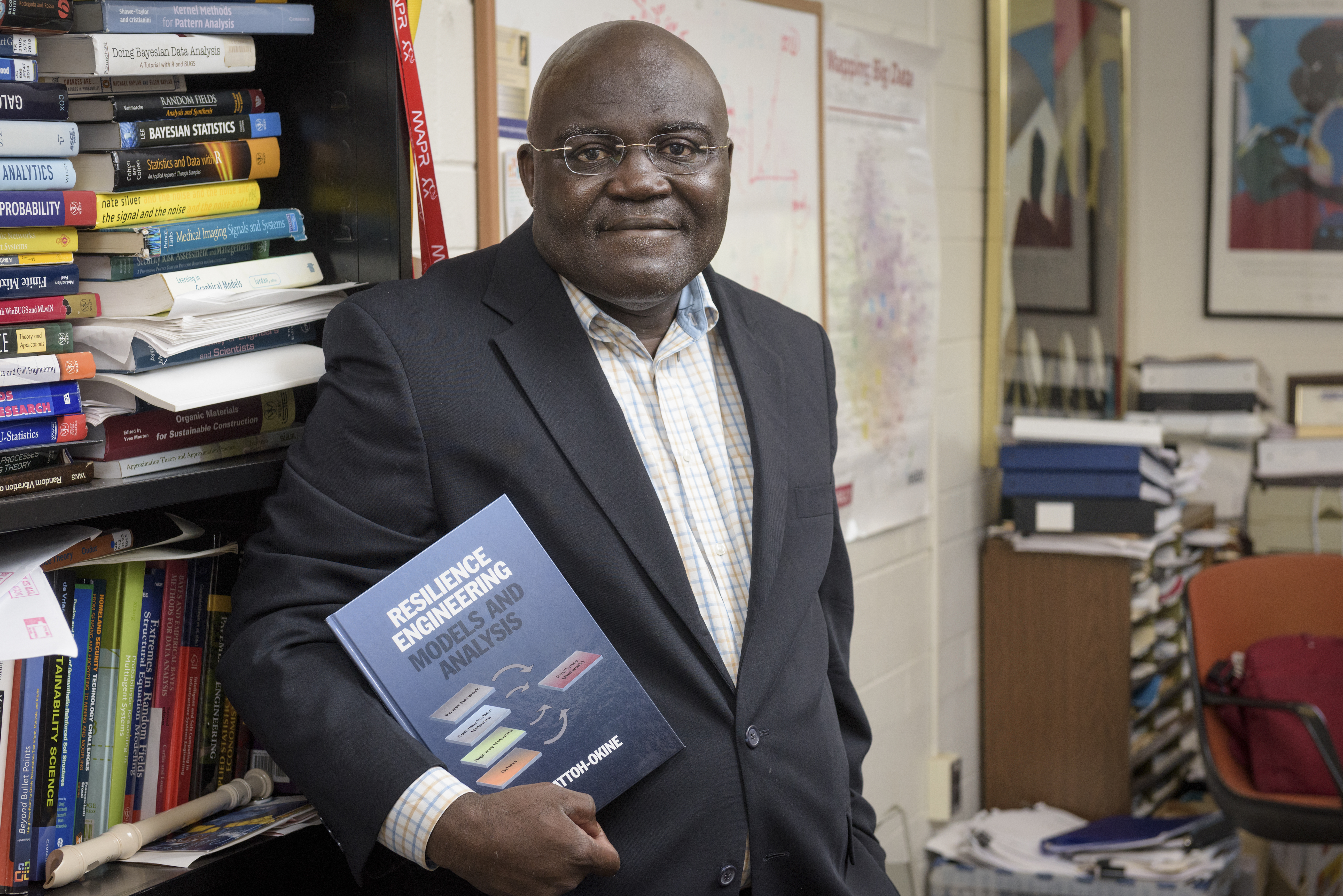

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

How this came to pass is the subject of Pivotal Policies in Delaware: From Desegregation to Deregulation, by William W. Boyer, Charles Polk Messick Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations, and Edward C. Ratledge, director of the Center for Applied Demography and Survey.

Published by the University of Delaware Press, the book looks at a series of pivotal policy events in modern Delaware, beginning with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, which the authors note “would eventually prohibit official racial segregation throughout the public schools of the United States.”

During an interview with the authors, Boyer noted that although Delaware was a slave state, the majority of Delaware blacks were free by the end of the 18th century. “According to local historian William H. Williams, Delaware, prior to the Civil War, became the least hospitable place in the Union for free blacks, due to an intense racism that endured through the mid-20th century, Boyer said.”

The state’s legacy of deep racial division, coupled with its failure to establish public schools of any kind until 1829, with none for African Americans until 1870, led to blacks not having equal access to public education until Delaware was forced to desegregate its public schools as demanded by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education.

Pioneering civil rights attorney Louis L. Redding, who had successfully fought to have the University of Delaware open its doors to black students in 1950, filed two suits in Chancery Court challenging segregation in New Castle County public schools. The court combined the suits in Belton v. Gebhart in 1952, which became an integral part of the Brown v. Board Education case presented before the Supreme Court by the NAACP’s chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall.

Despite the historic decision, it took decades for Delaware to desegregate its public schools to the satisfaction of the federal judiciary, with the most fierce and prolonged resistance occurring in New Castle County, Ratledge said.

“It was not until the late 1970s that Delaware officials become serious about desegregating the state’s public schools,” Ratledge said. “It took 40 years before a federal district court would say that the state was in compliance to school desegregation as mandated by the court.”

Ratledge also noted that the U.S. Supreme Court also was involved in significantly shifting political power in the Delaware General Assembly away from the state’s two lower counties as a result of the “one person, one vote” ruling in the 1964 Alabama v. Sims decision.

“The ruling ended the overrepresentation of rural counties in several states, including Delaware, and as a result, New Castle County, the state’s most populous county, became the controlling force in the state legislature,” Ratledge said. “Today, with the population shifting downstate, the power in the legislature also will be shifting south, and this will be an important thing to watch.”

Business first and activist governors

The evolving public policy scene in Delaware also was marked by was the advent of the activist governor, which the authors believe started with the election of Russell W. Peterson in 1968. The power of the governor was most fully realized during the administration of former Gov. Pierre S. du Pont IV, the state’s top executive from mid-1977 through mid-January, 1985, Boyer noted.

“Gov. Peterson started a lot of new things, including introducing the cabinet system of government and the passing of the Costal Zoning Act,” Boyer said. “Gov. du Pont restored the pro-business climate in the state with the passage of the Financial Center Development Act of 1981, which brought many out-of-state credit card banks to Delaware.”

Key public policy decisions also included the nine-month deployment of the Delaware National Guard in Wilmington following the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, the deregulation of utilities, confronting Delaware’s high cancer rate and a hard-nosed approach to crime and punishment.

In the late 1970s, the community-based corrections program advocated by Gov. du Pont began to be eased out by a rigid criminal code that emphasized minimum mandatory sentencing and incarceration. By the early 1990s, Delaware led all states in the rate of incarceration.

“The community-based corrections systems says prison administration should be geared toward rehabilitation, and this became more and more ignored,” Boyer said. “Delaware took a more punitive approach. We are not as good at rehabilitating people as we are at incarcerating them.”

One of the results of this approach is that mandatory sentencing put a lot of people in jail that probably didn’t belong there, which resulted in overcrowding in the state’s prison system, Ratledge said.

“The pendulum of public opinion is swinging the other way now, away from mandatory sentencing,” Ratledge said. “It’s not completely done, but with the effect of the recession, the state and federal government has less and less money to spend on prisons.”

The authors noted that, as with all public policy decisions, the outcomes are not always what the supporters of such policies had envisioned.

“There have been good things, like the ban on indoor smoking and the seat belt laws, which made good sense and have had immediate benefits,” Boyer said. “There also are many difficult issues generating a lot of conflict between polarizing groups with nobody wanting to give in. What is needed are policies that are sustainable in the long run.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson