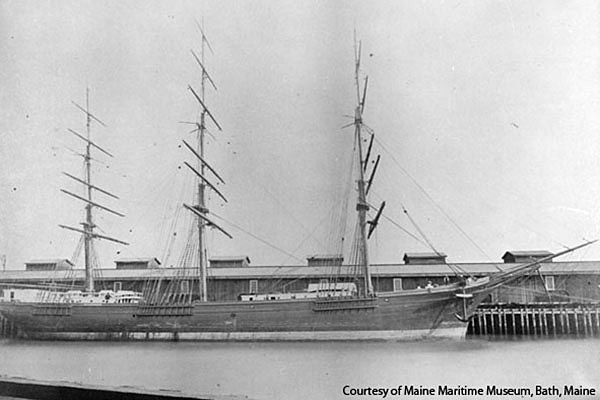

Shipwreck mystery solved

Lewes wreck found to be W.R. Grace, ship destroyed in 1889 hurricane

1:10 p.m., Aug. 8, 2012--University of Delaware researchers have discovered that a shipwreck near the coast of Cape Henlopen is a 215-footlong sailing vessel destroyed by a hurricane more than a century ago.

Scientific surveys and historical records indicate that the wreck is the W.R. Grace, a three-masted ship that ran aground during a hurricane on Sept. 12, 1889.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

“It was not something we expected to be as old as it was,” said Arthur Trembanis, associate professor of oceanography and geological sciences in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment.

Trembanis' research group came upon the shipwreck two years ago while training undergraduates to use remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and other ocean surveying equipment along the coast of Cape Henlopen State Park near Lewes, Del. They were surprised to find that the wreck was not included in a public federal database of known shipwrecks and other potential navigation hazards.

Delaware’s coast has been the site of hundreds of shipwrecks over nearly four centuries, making identification a challenge – particularly with older wooden ships disintegrating over time. State archaeologists initially suspected that this unknown wreck was made of iron or steel since it was readily picked up on sonar, possibly a military or freight vessel dating to World War I or later.

Trembanis partnered with Jeff Snyder, president of SeaVision Underwater Solutions, a commercial marine surveyor, to revisit the site in June and obtain better images with side-scan sonar and video technology. They were able to pinpoint the exact location, orientation and size of the wreck, which sits about seven meters below the surface.

Oceanography graduate student Carter DuVal then consulted a book about shipwrecks in the Mid-Atlantic and other sources to begin cross-referencing their field findings with historical clues. Maritime records revealed that the dimensions of the W.R. Grace, built in 1873, matched that of the wreck, and the ship had a metal sheath around the hull to prevent marine growth.

DuVal also researched newspaper accounts about the ship’s fate when a strong hurricane struck the coast in 1889. Apparently the massive ship had difficulty navigating the shallow waters around Cape Henlopen, and after dropping anchor to ride out the storm, the ship drifted and lodged into the sand below.

The vessel was carrying 7,000 empty petroleum barrels from France to refill in Philadelphia and ship to Japan. With the W.R. Grace a loss, operator Flynn and Company sold the barrels at auction.

“When we found the wreck itself, we noticed that there doesn’t appear to be any cargo in the hold,” DuVal said. “So that is also something that points to our wreck being the W.R. Grace.”

Today the ship is covered in dense clusters of blue mussels and frilled anemones, forming an artificial reef similar to others built around Delaware Bay. The invertebrates need hard surfaces to latch onto and form colonies, which are not easy to find along the sandy coastal zone.

“If they encounter something, they colonize pretty quickly,” Doug Miller, associate professor of oceanography, said, adding that a significant population can manifest in just a few years. “It’s indicative that our coastal shallow waters are very, very productive.”

The sandy coastal features seem to have prevented life from taking hold on the wreck until relatively recently: The ship appears to have been previously buried. Swift currents help move the ocean floor in this area into a series of ripples, with conditions so turbulent that the sandy tip of Cape Henlopen extends about nine meters each year.

A 1995 study of the area did not reveal the wreck, yet the ship’s outline did appear on a 2007 National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration survey (the results were not included in the public database). So either the wreck was uncovered sometime between 1995 and 2007, Trembanis said, or it has undergone periods of burial and exposure.

State archaeologist Craig Lukezic said he has frequently encountered those kinds of changes while studying shipwrecks. He said a scuba dive investigation could reveal more information about the wreck, such as the architecture of the boat, but there are probably no artifacts left on the ship since the contents were salvaged before it submerged.

Such a dive would need to be conducted in cooperation with the state, as the wreck is protected by law under the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act, and the currents make diving in the area treacherous.

“It makes it very difficult and very dangerous,” Lukezic said.

For now, the ROV and sonar findings can be used to better understand the ocean dynamics that impact wrecks, compare the site to other reefs and study how the ocean floor changes over time. “We’re in an exciting time for this kind of exploration,” Trembanis said. “In our own backyard are some exciting new discoveries.”

Article and video by Teresa Messmore

Images courtesy Arthur Trembanis and the Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, Maine