Hillel dialogue

World Food Prize laureate calls for sustainable soil, water management practices

10:40 a.m., April 15, 2013--As the population of the world soars toward 9 billion by midcentury, sustainable agriculture pioneer Daniel Hillel is “conditionally optimistic” that humanity will find a way to feed up to two billion more people in the coming decades.

Hillel addressed the audience gathered for the most recent DENIN Dialogue talk, sponsored by the Delaware Environmental Institute (DENIN), on April 4. Robin Morgan, professor and former dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, hosted the discussion in the University of Delaware’s Mitchell Hall.

People Stories

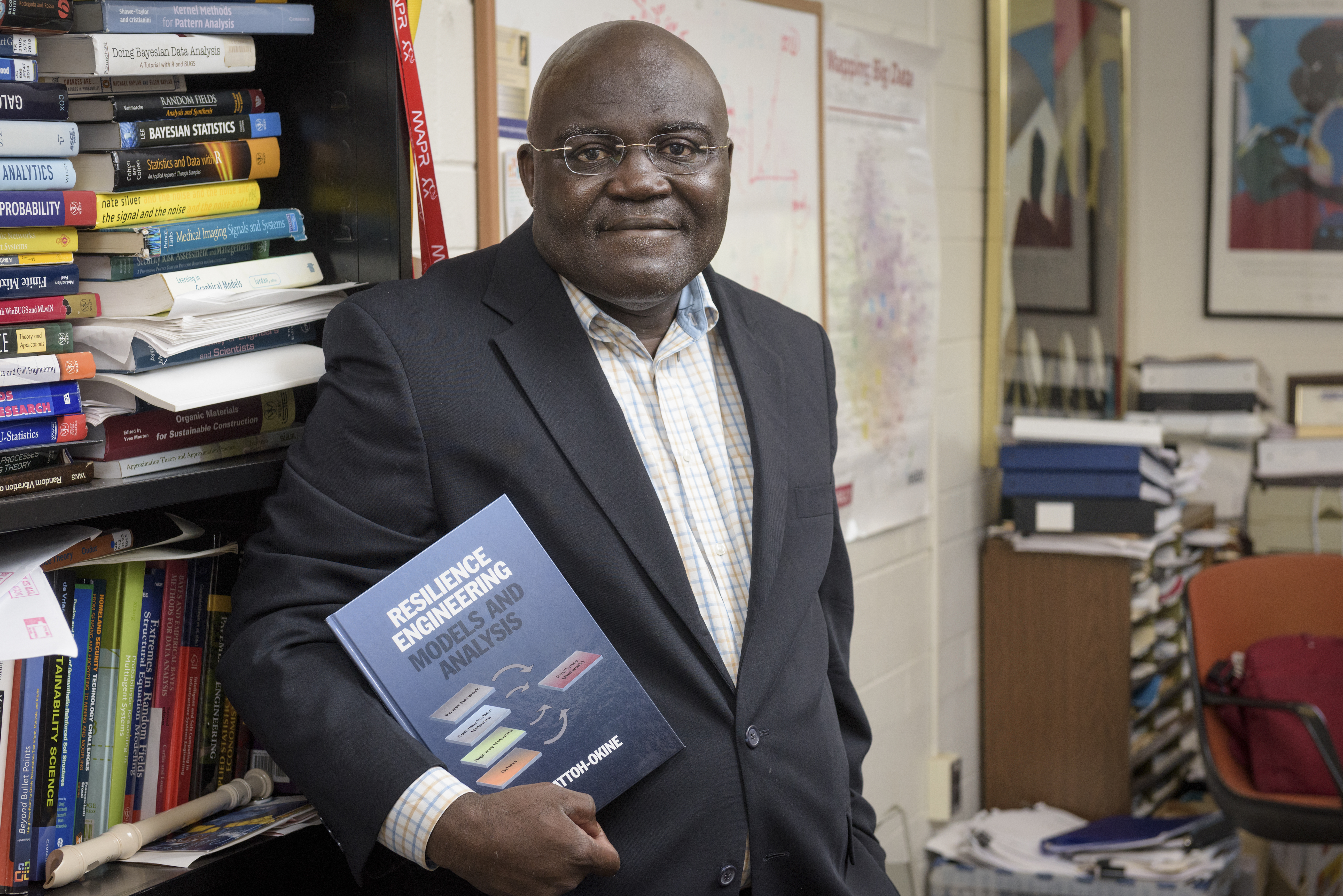

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

The 83-year-old Hillel was the winner of the 2012 World Food Prize, considered to be the “Nobel Prize of Agriculture,” for his work developing micro-irrigation techniques and promoting their use around the world.

Born in the United States and raised in what was then Palestine, Hillel was among the idealistic Jewish settlers who worked to build agricultural productivity in the newly formed nation of Israel. Trained as a soil scientist at both American and Israeli universities, Hillel sought ways to turn arid lands into productive farms. He demonstrated that water applied in small but continuous amounts directly to plant roots resulted in dramatic increases in both plant production and water conservation.

Morgan opened the discussion by asking Hillel to define “soil,” which he described as “the living outer portion of the Earth’s continental surface” where bedrock, the atmosphere and precipitation mix and where myriad life forms help to break down and churn the particles. “It is where life is generated and sustained,” he said.

Far from being “dirty,” healthy soil is “a great cleanser,” where beneficial microbes decompose and recycle wastes and defeat disease-causing microbes, Hillel said. He pointed out that many antibiotics used to fight infectious diseases originated with soil microorganisms.

Feeding the world of the future, he said “will only be possible if we manage the life-giving resources of the Earth judiciously, responsibly — not only conservatively, but constructively. We have to intensify our management of selected tracts of land in a sustainable way, a way that will improve the productive potential of the land.”

Morgan noted that most of the agricultural advances of the past century have come about through increased use of fossil fuels for pumping water, producing fertilizers and pesticides, and powering farm machinery. While this has enabled us largely to keep pace with growing food demand thus far, it is not sustainable in the long term, according to Hillel.

Noting that the sun, through green vegetation, is the ultimate source of most of our energy, Hillel expressed hope that alternative energy sources can be employed in agriculture and elsewhere.

“The history of humanity is a contest between learning and a disaster,” he said, citing English Renaissance writer Ben Jonson. “I have never stopped being a student. And I suggest that none of us ever stop being a student. If we stop learning, we’ll encounter disaster.”

Morgan also asked about his studies of the ancient civilizations of the Middle East and the roles soil and water played in their rise and fall. Hillel said that it was true that Egyptian civilization persisted and flourished while those of early Mesopotamia did not largely because of differences in the geology and hydrology of the Nile River valley versus that of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

“The story of Egypt is very, very interesting, very significant,” Hillel said. He said that archeological evidence and census data taken when European imperial powers began to invade the country shows that the human population of Egypt remained fairly stable between 1.5 and 4 million people for millennia. The population grew in times of agricultural plenty and declined in periods of famine that were tied largely to the flooding cycles of the Nile.

“Today, the population of Egypt is well over 80 million. And what caused this change, of course, was the introduction of modern medicine and sanitation. So the population began to grow, but the land and water base remained the same,” Hillel said.

Ultimately, the Nile River was dammed at Aswan, enabling Egyptian farmers to develop a perennial irrigation system that supported several crops per year rather than relying on the Nile’s seasonal flooding. This allowed continued population growth for a few decades, Hillel said, but Egypt is now again in danger of exceeding the productive capacity of its land.

Hillel said that the world must slow overall population growth, “not by coercion but by education,” if we are not to exceed the capacity of the global environment.

“We live on a single globe,” he said. “It’s all integrated. The same atmosphere envelops all of us. Climate change is going to affect the entire world. Not a single nation will be able to escape the consequences of our mismanagement. So, we must think globally and act globally.”

Hillel said we must live up to our species name. “We named ourselves Homo sapiens, and that’s a pretentious name. Homo means ‘of the Earth,’ of humus, and sapiens means ‘wise.’ So we flatter ourselves thinking that we’re ‘wise earthlings.’ We haven’t always been very wise in the past,” he said. “We have to get wiser.”

The DENIN Dialogue Series engages experts from around the world in conversation about pressing environmental issues. This dialogue was part of the “Challenges and Choices” series of events being hosted by DENIN in 2013 to focus attention on four major environmental challenges facing Delaware: sea level rise and extreme weather events, food and water security, land use and energy.

Article by Beth Chajes

Photos by Evan Krape