Gladiators and gore

Lecture provides a window into blood sports of the Roman Empire

10:30 a.m., Nov. 14, 2011--Gladiator combat can tell us a great deal about ancient Roman society, but we have no evidence from gladiators themselves about the experience. So classical scholars like Kathleen Coleman are challenged to become classical sleuths, using art, artifacts and architecture to reconstruct the rules and traditions of Roman blood sports.

Coleman, the James Loeb Professor of Classics at Harvard University, painted a vivid picture of organized violence in ancient Rome to a standing-room-only crowd of more than 300 people at the University of Delaware on Thursday, Nov. 10. Her lecture, “The Virtues of Violence: Amphitheaters, Gladiators and the Roman System of Values,” was part of the Distinguished Scholars Lecture Series of UD’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures.

People Stories

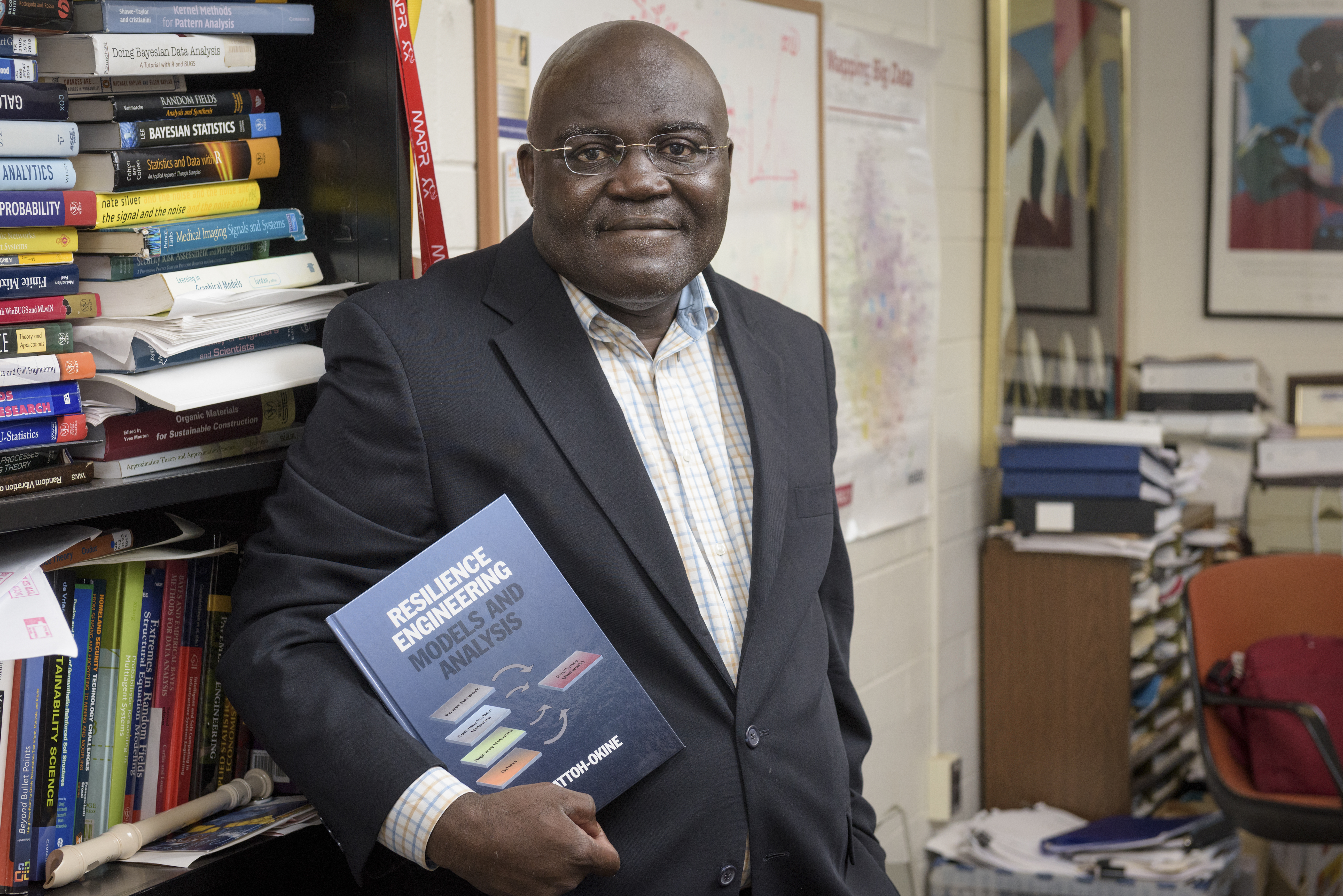

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

Coleman explained how the details on 2,000-year-old mosaics, reliefs, tombstones, paintings, medallions, coins, jugs and plates provide insight into how the sport was organized, refereed and watched.

For example, she showed one image depicting a gladiator holding up a finger for mercy and another displaying a gladiator with his foot on the hand of his downed opponent. These pictures suggest that while blood and gore were an integral part of the sport, death was not necessarily the desired end. “Gladiators were slaves,” Coleman said. “They were a capital investment of their owners, who didn’t want them killed.”

But perhaps most telling is the setting where gladiatorial combat took place. “The Coliseum was a highly sophisticated building that serves as an index to us of the value the Romans placed on this violent activity,” Coleman said.

She gave the audience a visual tour of the structure, which featured a broad array of architectural and mechanical details, including awnings, pulleys, ramps, arcades, gates and trapdoors. A hierarchical seating plan carefully separated spectators by class and gender.

“That chaos of blood, fighting, wounding, and terror took place within a highly ordered infrastructure,” Coleman said. “The entrances and seating were arranged in such a way that you wouldn’t have to come in contact with anyone of the ‘wrong’ class as you came into the building.”

Animals from leopards and lions to bears and bulls were an important element in ancient blood sports. Once again, Coleman showed that the Romans went all out in this effort, which involved elaborate strategies for capturing, importing and displaying the creatures in a realistic environment.

“The spaces included scenery such as plants and hillocks, resulting in an event that was more like a theatrical production than a football game,” Coleman explained. “The Romans recreated the wild to make it more authentic and provided a kind of zoology lesson for spectators.”

New discoveries continue to shed new light on the Roman world. In the early 1990s, for example, a gladiatorial cemetery was discovered in Ephesus, Turkey, providing detailed information about the types of wounds sustained by the participants. DNA tests also show high levels of strontium in the remains, which suggests that the combatants consumed a high-carbohydrate diet.

These sports, which began as funerary ceremonies and morphed into public entertainment, spread thousands of miles across the Roman Empire from northern England to Iraq. The Romans leveled entire communities to build coliseums where people of all social and political ranks came together to watch organized cruelty to animals and other humans.

“It was a perfectly ordered microcosm of Roman society, and it took place on the biggest playground of the Roman Empire,” Coleman said.

Gladiator trivia

- Sculptural reliefs depicting horns were discovered in 2006 and suggest that music accompanied gladiator combat.

- Gladiators’ helmets were extremely heavy, so battles probably didn’t last long.

- Gladiators became specialized over time, with at least seven different classes categorized by their protective equipment and weapons.

- Umpires controlled this highly professional form of combat.

- The Romans named the leopards in their shows, suggesting that these animals were a star attraction.

- Roman blood sport also included public beheading of prisoners.

About Prof. Coleman

Kathleen Coleman was born and raised in Zimbabwe. Before joining the Harvard faculty in 1998, she taught at the University of Cape Town and held the chair of Latin at Trinity College, Dublin.

Among her many accomplishments, she has been a fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung, a Harvard College Professor appointee—a five-year appointment in recognition of contributions to teaching—and the recipient of the Walter Channing Cabot Fellowship, an annual award given to Harvard faculty members in recognition of achievements in literature, history or art.

She is the editor of Harvard Studies in Classical Philology (Vols. 105–106) and co-editor of Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature, a series published by Oxford University Press.

She is the American delegate to the Internationale Thesaurus-Kommission in Munich, Germany, and president of the American Philological Association.

Article by Diane Kukich

Photo by Doug Baker