Stitches in time go online

UD leads national project to create digital archive of Early American samplers

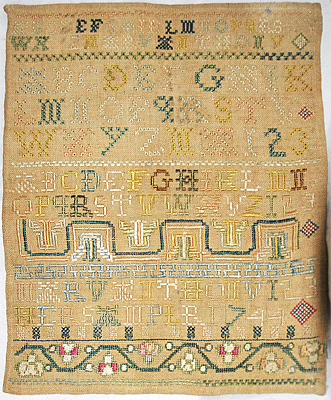

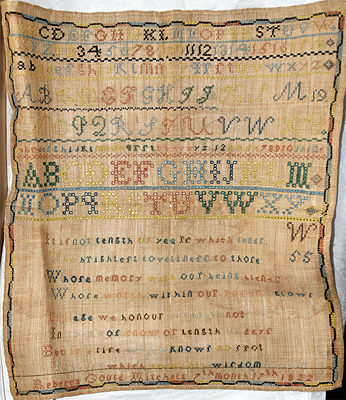

12:47 p.m., July 5, 2011--Proudly displaying numerals and ABCs, scenes of faith and farm life, Bible verses and witticisms, the samplers embroidered by girls in colonial America not only brightened the home, but also shone the light of literacy into the needleworkers’ young lives.

To bring these historic American treasures to the public eye, the University of Delaware in collaboration with the University of Oregon is now launching the Sampler Archive Project, a major effort to build a national digital archive and searchable database of samplers stitched by American girls in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. UD won a $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to develop the resource.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

The project involves UD, the University of Oregon, the international Sampler Consortium of scholars and collectors, and museums with significant sampler collections.

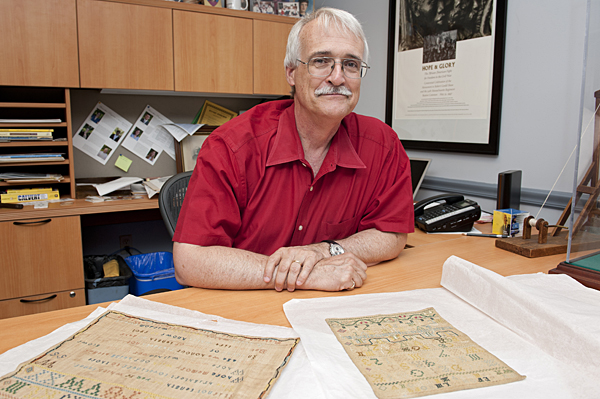

According to Ritchie Garrison, professor of history and director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at UD, the work is all about enlisting technology to connect the public with its cultural legacy.

“This project brings two great universities with deep strengths in American material culture and advanced digital technology together with a consortium of curators and collectors passionate about the study of historic samplers,” notes Garrison, who serves as the project’s leader. “We hope to do for American samplers what has been done for American quilts, creating another important portal into the nation’s heritage.”

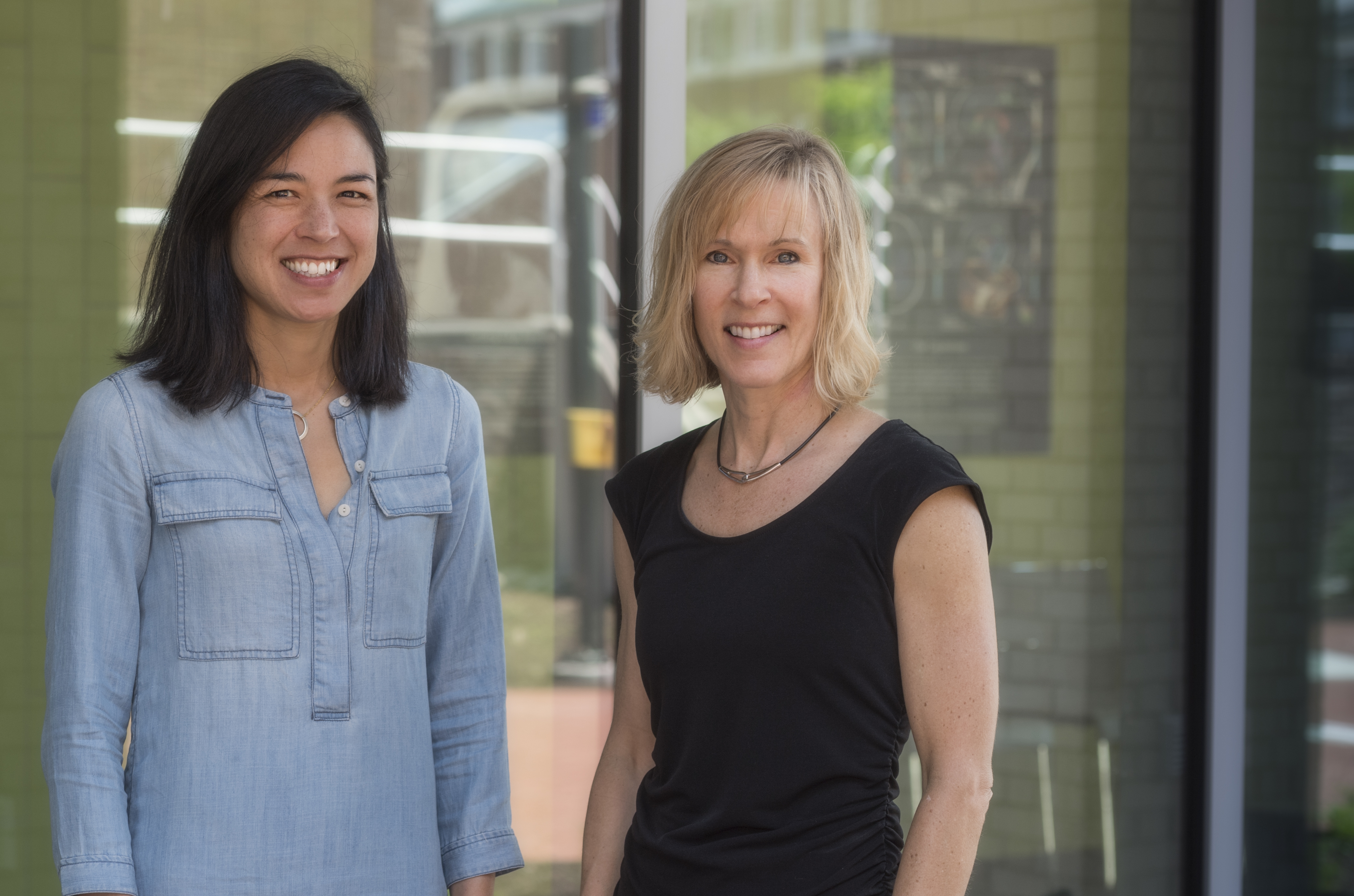

Garrison’s co-investigators include Lynne Anderson, associate professor at the Center for Advanced Technology in Education at the University of Oregon; Patricia Keller, who earned both her master’s degree in American material culture and doctorate in American civilization at UD; and Linda Eaton, curator of textiles at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, the museum of American decorative arts established by Henry Francis du Pont in Delaware.

The team begins work this summer with Winterthur’s 125 samplers, to be followed later by the sampler collections of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in Washington, D.C., and the Rhode Island Historical Society in Providence.

“Sampler” is derived from the Latin word “exemplum,” which means “an example to be followed.” Young girls, typically from six to 15 years old, would learn different stitches as they created the works, gaining skills they could use for the rest of their lives.

Garrison notes that stitchery skills were vital to a family’s welfare. Clothing was expensive and usually mended or remade rather than discarded. In addition, some women depended on such skills to earn a livelihood.

The first recorded sampler was made in England in 1598 by a Jane Bostocke. The work, with its elaborate geometric patterns, a dog, deer, and flowers, is held in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

“There were English sampler themes and American sampler themes, and design ideas crossed the ocean,” Garrison says. “This was an ‘Atlantic world’ form of expression done largely by girls in schools.”

Girls copied patterns to the point that you could identify a particular school, Garrison says, but as they were copying, they were learning to read and write, as well as to stitch and embroider.

Sampler work began to drop off in America in the 1830s, as more educational opportunities became available to girls. However, this form of needlework persisted in some areas. In the late 19th century, Native Americans on reservations sometimes created samplers.

Today, Garrison and his scholarly collaborator Anderson estimate that as many as 10,000 samplers still exist.

“Our hope is that historical societies, art museums, private collectors and families will all contribute photos of their samplers to the archive in the future,” Garrison notes.

Article by Tracey Bryant

Photo by Evan Krape