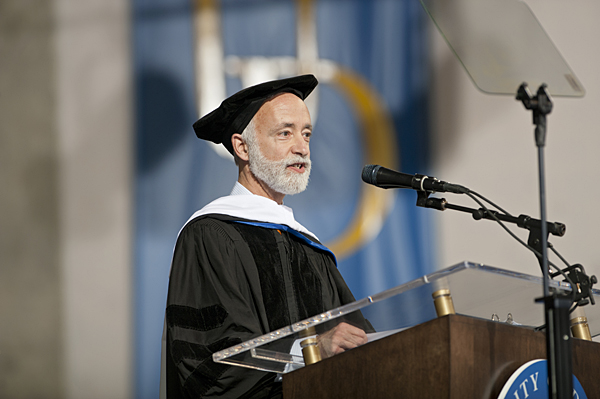

Encouraging words

Naturalist Robert McCracken Peck speaks at UD's Winter Commencement

2:55 p.m., Jan. 9, 2012--Robert McCracken Peck received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree at the University of Delaware Winter Commencement, held Jan. 8 at the Bob Carpenter Sports/Convocation Center. Following is the text of his remarks to the graduates.

Campus Stories

From graduates, faculty

Doctoral hooding

Thank you and hello everyone. I am deeply honored by the University’s decision to grant me this special degree, and even more honored by the invitation to speak to you this afternoon. The challenge, of course, is how to find something to say in the few minutes I have been given, that will be meaningful to you in the context of all that you have achieved, and all that you are hoping to achieve in the years ahead.

If time would permit, I would love to be able to speak with each of you individually to learn about your academic interests, you career goals and where you would most like to see yourself 10 years from today. Absent that direct communication, it would be presumptuous of me to offer you advice. What I can do is give you encouragement as you embark on the next important stage of your life.

Each of you has a unique combination of talents and experiences to offer the world. Don’t be afraid to let them show. They are what will make you stand out and will ultimately allow you to make your greatest contributions.

The other encouragement I would give may seem obvious, but can be easily overlooked in the rush to find a job, and that is try to do something that you love. Life is too short to pretend to be something you’re not, and too precious to let pass in boredom or misery.

You are here today to celebrate with friends and family the culmination of an important part of your education, and the beginning of another. Some of you will be remaining in school to earn another degree; others may be ready to plunge into a career. A few of you may be planning to take time off to give yourself a chance to think about what you would like to do in the years ahead.

When I was sitting where you are now, like many of you, I was unsure about what would be the best career path for me to pursue, for what I had studied, and what I wanted to do, were not exactly the same. The degrees that I had in art history, archaeology and American cultural history were in subjects that had interested me academically and engaged me intellectually during my time in college and graduate school (happily, they still do), but my passions were for natural history and wildlife conservation, both subjects I had pursued outside of the classroom. I wanted to travel the world and save endangered places and the wildlife that lived there. The question was how to bridge this seeming gap between my formal education and a strong motivation to do something helpful for the natural world.

I mention this apparent disconnect between heart and mind because I believe it is a tension that many people experience. It is especially acute when we leave the relative security of school and face the uncertainties of the workplace. I want to reassure those of you who are feeling that tension now, that the distance between the two may not be as great as you think, and that you need not necessarily abandon one for the other.

When I left the University of Delaware in 1976, I took a job at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, the oldest natural history museum and research institution in North America. It was an institution I knew something about for I had done volunteer work there during high school and college. I knew of its history and its international reputation for scientific research. Being there, I hoped, might allow me to combine my personal commitment to environmental stewardship with my academic interest in history, for, as part of its contemporary research program, I knew that the academy cared for an extraordinary array of historical collections.

These include, among other things, all of the surviving plants, minerals and fossils collected by Lewis and Clark on their epic journey across America, and fossils of mastodons and other prehistoric creatures originally owned by Thomas Jefferson. Today Jefferson’s fossils and Lewis and Clark’s plants are housed at the academy, along with birds collected by the great painter and naturalist John James Audubon; fish caught for the museum in the waters off Cuba by novelist Ernest Hemingway; and plants gathered by the pioneering conservationist John Muir in the High Sierra of California. These collections, totaling more than 17 million scientific specimens in all, combine to form an irreplaceable genetic library of life on earth.

I love being in the company of such objects, and the opportunity to share my days with some 200 scientists whose environmental research projects take them all over the world, but I confess that when I first arrived at the academy, I felt like a bit of an imposter. With my liberal arts training, what was I doing in a natural science museum? What could I bring to this table that was already set with such an august history and populated with so many distinguished scientists? The answers, I discovered, were the very things I thought were irrelevant to the scientific process -- my training in history, art and literature. And so, by applying my expertise in the humanities to the field of science, and by letting my enthusiasm for linking the two bubble to the surface, I slowly became the academy’s in-house humanist whose job it became to help put what our scientists do into a broad cultural context through exhibitions, lectures, documentaries, and a range of publications, both popular and academic. By breaking down the perceived barriers between disciplines and communicating the relevance of the academy’s science to the day-to-day lives of the average citizen, I found that I was also able to remove the tension I had felt between heart and mind when I left the University.

I could hardly believe my good fortune when I began to be invited to participate in research expeditions to parts of the world that I’d read about in National Geographic, but never imagined I would see for myself. I joined scientists studying fish in the Amazon, birds in the Andes and insects in the Kalahari Desert.

When I wasn’t in Philadelphia writing about what goes on behind the scenes in the museum, I found myself with teams of scientists exploring Namibia’s Skeleton Coast, observing baboon behavior in Botswana’s Okavango Delta and recording the sonar-like clicks of electric fish in Venezuela’s Orinoco River. I discovered that by playing a meaningful role in the research, I was better able to put what we had done into laymen’s terms and to explain it to the public. This, in turn, earned more invitations to join scientists in the field. And so it went, one amazing experience after another….

It was like taking a series of graduate-school seminars in every imaginable subject, combined with extended periods of extreme sports and all in interesting and spectacularly beautiful settings, only now I was being paid to participate, and not the other way around! By allowing my disparate interests and eclectic course work to merge, I was able to create a new job bridging the gap that exists between the sciences and the humanities; between the specialists, and the interested, but sometimes forgotten, public. Most important of all, the work that I was now a part of was having a direct impact on science, on education and on wildlife conservation, for our discoveries lie at the foundation of our education and conservation programs and are used by governments and conservation groups, in the U.S. and around the world to determine what organisms are threatened and in need of protection. It is the gratifying blend of heart and mind that I had thought impossible to achieve when I first ventured out of school and into the workplace.

Thirty-five years after I arrived at the academy, I still feel the overwhelming sense of excitement and energy I felt on that first day I arrived there. In the years that have passed between earning my last degree and receiving this one, I have learned that continuing to grow and to think creatively are keys to success; that the lines between disciplines can be blurry; and that sometimes the most interesting discoveries are made at the intersections of different disciplines. Above all, I have learned that if you are doing something that you enjoy and believe in; you can meet or exceed even your most ambitious goals.

I am extremely lucky in having found (or perhaps I should say created) a job that I absolutely love, but that is not to say that the job (or any job) is fun 100 percent of the time. Finding financial support in the not-for-profit world is always a challenge, which means lots of proposal writing and, if successful, lots of reports to document the achievement of what has been proposed.

Even the research expeditions that I consider the best part of my job can have their ups and downs. Though I wouldn’t trade them for anything, some of the downs can be more than a little bit challenging -- like traveling in the Sayan Mountains on the Siberian border in the depths of winter and having the wheel wells in our Russian jeep freeze solid, stranding four of us 100 miles from the nearest settlement, with the temperature at 30 below zero and wind chills that would freeze water before it hit the ground; or having to live for weeks on yak fat, goat entrails and fermented mare’s milk, while traveling with nomadic herdsmen in Mongolia. I have seen colleagues chewed by piranas in the Oronoco and watched parasitic maggots the size of jellybeans erupt from boils in my arms during a trip to the Amazon. My original job description never mentioned these possibilities, but since I had shaped my job to fit my interests, I had no reason to complain. Nor did I expect any sympathy. These are all dues I have been happy to pay for the privilege of visiting some of the last unspoiled places on earth and having the chance to help protect them from destruction by explaining their importance to the outside world.

Of course, there are many trade-offs one has to make in one’s life and career, for nothing comes without a price. The calculation you will have to make is how best to balance the price and the reward.

In these troubled economic times, we hear a lot about the disparity between the 1 percent and the 99 percent. But there are other ways to assess reward than by salary alone. The Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan famously prizes its gross national happiness more than its gross national product. You can do the same. As long as you can pay the bills, if you can find a career that speaks to your soul, and if you can do something to improve the world, then your professional life and your personal life can become a seamless and gratifying whole.

There is an old adage that says “he or she is a success who lives well, laughs often and brings happiness to children.” I would only add to that, what you do for others and for the world at large are the things that will give you the greatest satisfaction in the long run. As you look back on what you have achieved 10, 20 or 30 years from now, you will be happy with yourself if you have made a significant difference. Don’t let that opportunity pass you by.

I want to congratulate you on the degrees you have earned and on the diplomas you will receive today. I know you will make your families and the University proud by what you do with them. Be sure you make yourselves proud, too, by remembering to nurture your hopes and dreams, not just now, but for the rest of your life. Your individuality and your idealism and your education are three of your greatest assets. If you stay true to these, you can not help but have a productive, useful and fulfilling life. Congratulations.

Photo by Evan Krape