ADVERTISEMENT

- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

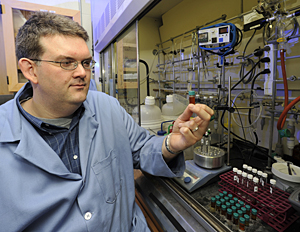

2:26 p.m., June 24, 2010----University of Delaware scientist Donald Watson is part of a research team that has discovered an easier method for incorporating fluorine into organic molecules, giving chemists an important new tool in developing materials ranging from new medicines to agricultural chemicals.

The research, which is reported in the June 25 edition of Science, was led by Stephen Buchwald, the Camille Dreyfus Professor of Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Watson worked in Buchwald's lab at MIT as a postdoctoral research associate prior to joining the UD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry as an assistant professor this past September.

About 25 percent of pharmaceuticals contain fluorine, according to Watson, but it's difficult to incorporate the element into drug molecules. Numerous researchers have been working to develop general methods to introduce fluorine atoms into organic molecules under mild reaction conditions.

“The introduction of fluorine atoms into a pharmaceutical compound can have pronounced effects,” Watson notes. “They can modulate the uptake of the drug and stabilize it against metabolism by the body, keeping it in a person's system longer and making it more effective.”

The chemical method discovered by the research team uses a soluble palladium (a precious metal) catalyst to replace a chlorine atom in an aromatic molecule with a trifluoromethyl (CF3) group, which contains one carbon and three fluorine atoms. The process is highly general and occurs under mild conditions, and may become even more economical in the future as less expensive reagents are identified, Watson says.

Watson's role in the research effort was in early stage development. He dissected the complex chemical process into manageable pieces, isolating the first compounds critical to the reaction and demonstrating their effectiveness.

This is the second article in this research field that the team has published in Science during the past year. The work on which the first article is based will result in Watson's first patent, co-authored with colleagues at MIT.

Today, in his laboratory at UD, Watson works on developing homogeneous transition metal-based catalysts for use in organic chemistry. He hopes the processes that he is discovering will find use in pharmaceutical, agrichemical, and alternative energy research.

His aim is to help build the chemist's toolkit, providing tools -- in the form of chemical reactions -- that other chemists can use to make new molecules.

“In my lab we do basic science that has the potential for real-world applications,” Watson says. “We're working with the nuts and bolts, getting to develop stuff that other scientists can use. It's exhilarating to do research that will impact the way chemists build molecules.

“Making molecules and new catalysts is exciting,” he adds. “To be able to sketch out a new compound and then make a new substance is a unique experience. It's pretty thrilling to be able to create new substances that other people have never seen before.”

Watson has a growing laboratory group, with three graduate students, an undergraduate student, and a laboratory assistant.

“They are an incredible group of hard-working and highly talented students, and their science will have an impact,” he says.

He knows that the experience in his lab has the potential to transform their lives just as his lab experiences did.

As an undergraduate, Watson explains, his interests were torn -- would he pursue physics, chemistry, or chemical engineering? Then as a sophomore in college he got involved in laboratory research in organic chemistry. The opportunity to work on something someone hadn't worked on before hooked him.

“I really like having undergraduate and early graduate students in the lab with me now,” Watson notes. “Being able to work with young scientists who are just getting started is very rewarding. I hope that I will be able to show them how exciting and important this field is. Being able to return that favor to others is a great privilege in this job.”

Article by Tracey Bryant

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson