- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

3:01 p.m., June 30, 2009----You might call it “math meets science,” but the quantitative biology major offered at the University of Delaware actually represents a curricular innovation employing problem-based learning and a multidisciplinary collaboration.

What it took to create the quantitative biology major and how it works was the topic of a talk given by John A. Pelesko, associate professor of mathematical sciences, on June 12 in McKinley Laboratory.

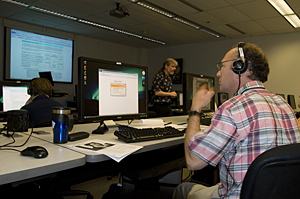

Pelesko's talk to about 30 faculty peers from several universities was part of the 31st annual Association for Biology Laboratory Education (ABLE) Conference held June 9-13 at UD.

The conference, hosted by ABLE members from UD's Department of Biological Sciences, brought more than 170 college faculty and laboratory professionals from throughout North America and served as a forum for the exchange of ideas to improve the undergraduate biology laboratory experience.

The talk by Pelesko was part of a number of workshops and presentations, many of which were led by UD faculty and staff.

“I want to give you a brief history of what motivated our efforts here at UD, and how we got involved in this,” Pelesko said. “I also would like to share with you some of the challenges we encountered and give you at least a sense of some of our solutions.”

Like a lot of curricular reform efforts in biology, the quantitative biology major at UD started with and was driven by the National Research Council's 2002 report, BIO 2010: Transforming Undergraduate Education for Future Research Biologists, Pelesko said.

“In BIO 2010, there is a focus on quantitative education in biology, an emphasis that runs through this entire report,” Pelesko said. “Buried in the report there also are other recommendations such as laboratory courses that focused on critical thinking skills, the opportunity to pursue independent research, an examination of teaching methods, adequate resources and faculty rewards.”

Pelesko said that UD actually had already identified some of the recommendations from that report, and had initiated the revision of laboratory courses and independent research opportunities for undergraduate students.

In noting that the history of undergraduate research at UD spans nearly three decades, Pelesko said a major boost to this effort began with the establishment of the Office of Undergraduate Research in 1983. This was followed, Pelesko said, by the introduction of problem-based learning in science courses in 1992, and the requirement of an investigative laboratory in biology established in 2002.

Pelesko also noted that the separation of Biology 101 and its lab component into two individual courses increased the number of components in course content and made it more innovative and interesting.

“The one thing we hadn't hit on was trying an interdisciplinary approach to bring more quantitative skills into biology,” Pelesko said. “We also wanted to bring more biology into the quantitative side.”

Another key factor in the development of the new major was the movement of major funding sources, including the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, towards funding interdisciplinary initiatives such as the quantitative biology major at UD.

Early challenges to the establishment of the new major included identifing and transcending culture barriers within different academic units, dealing with the disconnection between research and teaching, securing resources and dealing with curricular issues. Educating the faculty and administration about grants that require a quantitative biology approach and developing simulations and modules also was important, Pelesko said.

“The biggest step was getting the right group of faculty together and having them sit down and think about framing a course for students who may not be like them in terms of academic disciplines,” Pelesko said. “A team, consisting of one biologist (David Usher), a biochemist (Harold White), a chemical engineer (Prasad Dhurjati) and four mathematicians, (Tobin Driscoll, Louis Rossi, Gilberto Schleiniger and myself), in consultation with other colleagues, designed and proposed the new major.”

“We would sit in a room like this and go around and talk about what we did,” Pelesko said. “In time we learned each other's language.”

To strengthen interdisciplinary communication, mathematical sciences faculty joined with biological sciences faculty to find common ground and identify common ground material that works for both mathematics and biology, Pelesko said.

Also important was the sharing teaching goals, data, and methods and to integrate these efforts in the development of course content and major requirements, he said.

“We decided that it would be better for them to take the same calculus course that our engineers and physicists take, so we set up a separate section of our calculus class that had core biology interests but was open to anyone,” Pelesko said. “We tried to make it a non-parallel course, so students who take it and develop an increased interest in math could continue to take higher level courses.

“We had to convince the biologists that their students should take the special section of our calculus course, and we had to convince the mathematicians that we should reorient the calculus courses that the biology students had been taking before the quantitative biology major became available,” he said.

The new major also called for talking to talented undergraduate math majors and introducing them as teaching assistants in the biology labs, Pelesko said.

“We wanted them to be able to sit down and help the students when they had problems with statistics,” Pelesko said. “We also wanted to connect the calculus course with the first year biology sequence, so that the math students would be sitting down in the same class with biology students. This is surely a work in progress.”

The “math across the curriculum” initiative also involved the building of a library of instructional modules, loosely modeled on the Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse, Pelesko said. This process called for a survey of existing modules and the development of new modules by collaborative teams that also included the use of undergraduate and graduate research students with educational funding opportunities from HHMI, the Center for Teaching Effectiveness, and the National Science Foundation.

“One thing that we have learned as part of attending a national meeting held every year to discuss quantitative biology, is that everybody across the country is doing this,” Pelesko said. “There are a lot of people building these types of modules.”

The BIO 2010 report, Pelesko said, makes the argument that the next generation of research biologists needs to be quantitative literate, and that the program at UD is targeted towards attracting this group of students.

“We are not talking about the students who want to go to medical school, or the students who want to earn an undergraduate biology major,” Pelesko said. “We are targeting that group of students who want to go on to graduate school in either the life sciences, or perhaps in mathematics.”

Besides identifying a target student group, the involved faculty for the new major wanted to create classes where students would start seeing the connection between biology and mathematics, Pelesko said.

“The first way we did this was to develop integrated seminars. These are one-credit classes that the students have to take in both their sophomore and junior years,” Pelesko said. “What we do, is simply study one problem for the course of the semester. We sit down and read the literature and ask what can we do as mathematicians to build the module.”

The quantitative biology major also includes a capstone requirement called “systems biology,” which students have to take during their senior year, Pelesko said.

“Sustainability in the major depends on the continued renewal of integrative seminars and the capstone course,” Pelesko said. “These courses need to be refreshed by the involvement of multidisciplinary faculty and by guidance and enrichment from the local life science research community.”

Pelesko said that the University of Delaware's quantitative biology major is highly regarded by the HHMI, and was the central piece of a funded $1.5 million HHMI grant proposal.

In addition to being one of the very few majors of its kind at the undergraduate level, the program has attracted substantial attention from other schools across the country, and participating faculty have been invited to lead workshops at several national conferences sponsored by HHMI, Pelesko said.

“There are currently 15 students in the major at UD,” Pelesko said. “As the information on the major reaches more current and perspective students, the interest will continue to grow.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Doug Baker