- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

Editor's note: For a podcast of the presentation, see the UD Podcast Web site.

11:21 a.m., Feb. 17, 2009----When Jerry Marty left the South Pole in December, he walked under a canopy not of crossed swords but of crossed measuring tapes -- a fitting tribute to the man who oversaw one of the world's most challenging construction projects, the new South Pole Station.

Marty, facilities construction and maintenance manager at the National Science Foundation's Division of Antarctic Sciences in the Office of Polar Programs, shared highlights in the creation of this newest U.S. facility for polar research in his lecture, “Building for Science at the South Pole,” on Feb. 11 at the University of Delaware.

More than 100 people attended, including the packed seminar room in Memorial Hall and viewers watching the Webcast online and in UD's virtual world in Second Life.

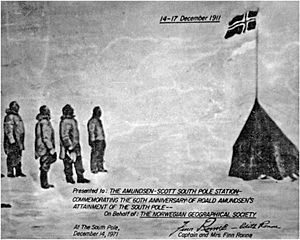

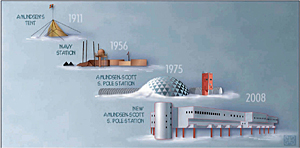

The facilities at the Earth's southernmost point have come a long way since Roald Amundsen and his team erected the first tent there in December 1911, staking their claim as the first to reach the South Pole.

Since then, scientific studies focusing on seismology to air quality, cosmic rays to climate change, have been launched at the bottom of the Earth.

The U.S. Navy Seabees built the first permanent South Pole research station in 1956-1957 in support of the International Geophysical Year. Within 10 years, the building was crowned by 33 feet of snow and today lies buried deep in the ice.

A new research station in the shape of a geodesic dome was dedicated in 1975. The Dome would periodically need to be dug out, with bulldozers pushing the snow nearly as far as a mile away from the structure to avoid rapid re-accumulation.

In 1999, Marty, who began his career as a general field assistant with the National Science Foundation's Antarctic Research Program in 1969, was asked to oversee construction of a new, elevated research facility to replace the Dome. Among its special features, this new station would have an angled wall to increase the wind speed under the structure to prevent snow from accumulating and hydraulic jack columns to lift the structure by an entire story out of future snow.

The project required precise ordering and shipping, down to the pound, of construction materials from the United States. Some components, such as the bolts used in the housing modules, were pre-tested at a facility in Little Rock, Ark.

Fuel and construction materials for the project were loaded on a ship at Port Hueneme, Calif., for the voyage across the Pacific Ocean to Christchurch, New Zealand, and then on to McMurdo Station on Ross Island, the logistics hub for the U.S. Antarctic Program. The supply vessel carries 10.5 million pounds of materials in, and 9 million pounds out -- to be recycled in Washington State.

“We were thinking 'green' some time ago,” Marty noted.

All the building materials had to fit within Hercules LC-130 aircraft, which fly from McMurdo to the South Pole.

“Our transport to the South Pole was no different than the space shuttle,” Marty said, noting that the cargo hold was packed to within an inch and to the maximum weight of 26,000 pounds.

Then there was the weather. In the 24-hour daylight of the Antarctic summer, temperatures could plummet to 56 below zero with the wind chill, he noted.

Additionally, continuing the science at the South Pole was a top priority during construction, and the logistical needs of two major research projects simultaneously had to be met, including the IceCube neutrino telescope, which involves researchers from the University of Delaware, and the South Pole Telescope.

Dedicated on Jan. 12, 2008, the new $153 million, 65,000-square-foot Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station has seminar and computer rooms and labs, comfortable dorm-like living quarters, and a greenhouse, among other amenities. Internet access is available nine hours a day when the satellite is overhead.

The building houses some 260 people during the summer and around 80 “winter-overs.”

By the time the new research station opened, Marty had spent nearly five years at the South Pole working on the project.

Nevertheless, he continues to be fascinated by the frozen continent that may hold answers to many scientific mysteries -- it's an interest that began in the one-room school in Wisconsin that he attended as a child, with its pull-down world maps and books about Admiral Byrd.

“It all started there,” he said, smiling. “It sparked a dream to go where few had gone.”

Earlier in the evening, Ian Janssen, director of University Archives, announced the acquisition of a large collection of papers and records of the late South Pole explorer and University of Delaware astrophysicist Martin A. Pomerantz. The collection is expected to be available to the public by early 2010.

The lecture was the latest offering in the William S. Carlson International Polar Year Events celebrating the University of Delaware's president from 1946-1950, who was an Arctic explorer, and UD's significant research in the fourth International Polar Year. The global scientific and education program began in March 2007 and concludes in March 2009.

Article by Tracey Bryant