University of Delaware and Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) scientists estimate that shipping-related particulate matter emissions are responsible for approximately 60,000 cardiopulmonary and lung cancer deaths annually, with impacts concentrated in coastal regions along major trade routes.

The results, scheduled to appear in the Dec. 15 issue of Environmental Science & Technology, mark the first time that researchers have estimated these effects globally. Previous studies have focused only on Europe and the western United States.

“We demonstrate that this is a multicontinental impact. You can't isolate the impacts to only one region,” said James Corbett, associate professor of marine policy and one of the study's two lead authors. “With more than half the world's population living in coastal regions and freight growth outpacing other sectors, all modes of goods movement will need to meet stricter control targets.”

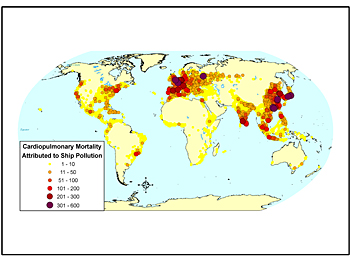

Corbett and James Winebrake, professor of public policy at RIT who co-led the study, determined that the areas most affected by particulate emissions are East Asia, South Asia and Europe, where large populations and high levels of shipping-related particulate matter coincide.

Particulate matter refers to tiny solid or liquid particles that are so small they are measured in microns (the width of a human hair is 75 microns). Particulate pollution can be composed of various substances, including metals, sulfur oxide and nitrogen oxide, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Oceangoing ships, which use high-sulfur fuels, are estimated to contribute 15 percent of global nitrogen oxide and 5 percent to 8 percent of global sulfur oxide emissions to the atmosphere each year.

Nitrogen oxide and sulfur oxide are known to create acid rain and degrade plant life as well as air visibility. But particulate matter suspended in the air we breathe also can have damaging human health effects. The small particles can enter the lungs and bloodstream, causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems including asthma, heart attacks and premature mortality. Particularly damaging are the tiniest of these particles, those measuring 2.5 microns and less, which studies have shown can increase cardiopulmonary and lung cancer mortalities in exposed populations.

To analyze the impact of these types of emissions from ships, the researchers estimated global and regional mortalities by integrating global ship inventories, atmospheric models and health impacts formulas. Comparing the atmospheric models with traffic data from the ship inventories allowed the team to quantify the ambient concentrations of particulate matter due to marine shipping. To estimate the size of populations exposed to the concentrations of particulate matter from shipping, Corbett and Winebrake consulted 2005 global population estimates.

Next, the researchers estimated mortality due to shipping emissions based on cardiopulmonary and lung cancer causes of death data from the World Health Organization and the EPA. They used an equation that examines the relationship between particulate matter concentrations and the mortality in a given region to arrive at their mortality estimates.

Corbett and Winebrake estimate that under current regulation, and given an expected growth in shipping activity, annual mortalities caused by ship-to-air emissions could increase 40 percent by 2012.

“In addition, there are other health impacts besides mortality that are exacerbated by these pollutants, such as respiratory illnesses like asthma, pneumonia and bronchitis,” Winebrake said. “Finding ways to reduce or eliminate these negative impacts will be an important and necessary task for policymakers.”

Currently, international policy discussions related to shipping emissions are led by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and centered on emissions reductions strategies--which could include switching to cleaner fuels or applying technology such as exhaust scrubbers--and methods for implementing and ensuring compliance with requirements. IMO, an agency of the United Nations, has a cross-governmental working group developing a study on shipping emissions that will influence possible changes to international regulations.

“Our work will help people decide at what scale action should be taken,” Corbett said. “We want our analysis to enable richer dialogue among stakeholders about how to improve the environment and economic performance of our freight systems.”

Their research was supported by the Oak Foundation, the German Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Deutscher Forschungszentren and the German Aerospace Center within the Young Investigators Group SeaKLIM.

Visit the Environmental Science & Technology web site at [http://pubs.acs.org/journals/esthag]. For more about UD's College of Marine and Earth Studies, visit [www.ocean.udel.edu].

Article by Elizabeth Boyle