EPSCoR has been a boon to Delaware since the program began here in 2003, helping researchers land more than $25 million in research and education grants. EPSCoR also has helped the state's colleges and universities attract talented new faculty members, improve research labs and launch new science programs. The National Science Foundation (NSF) established EPSCoR in 1979 in response to a Congressional requirement to assist states that have historically received less federal funding for research and development but are committed to developing their research initiatives and institutions. By promoting partnerships among state universities, industries and government in science and technology, EPSCoR's major goal is to maximize each state's resources and drive economic growth.

A diverse network of scientists, businesses, and educators

Attendees at the meeting emphasized that the diversity of Delaware's EPSCoR network, which includes four colleges and universities, is key to the program's success. “The collaboration among the University of Delaware, Delaware State University, Delaware Technical and Community College and Wesley College is an impressive interaction among organizations,” said Lance Haworth, director of NSF's Office of Integrative Activities.

Keynote speaker Larry Robinson, former chief executive officer of Florida A & M University and adviser to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, said that partnerships are the best way to leverage scientific resources. “EPSCoR tries to level the playing field by bringing resources, facilities, world-class faculty, students and programs together to improve national production. No one can argue that EPSCoR isn't good for the nation,” said Robinson, who credited EPSCoR with moving the country toward more diverse networks of high-quality research.

Donald L. Sparks, a partner in Delaware NSF-EPSCoR who also is the S. Hallock du Pont Chair, chairperson of UD's Department of Plant and Soil Sciences and the director of the Center for Critical Zone Research at UD, agreed with Robinson that the collaboration fostered by EPSCoR has been overwhelmingly positive. “We've built some really exciting networks with our teams across the state. We've had frequent meetings to look for ways we can enhance our interactions across the network, like new faculty start-up, seed grants, core facility enhancement around the state, seminars, workshops, meetings and sponsorships,” Sparks said.

Sparks is responsible for the development and execution of research in the network's Research Infrastructure Improvement (EPSCoR RII) grant. He said the interface among different disciplines is an important component of high-quality research and that networking and building partnerships with Delaware State, Delaware Tech and Wesley have been the highlights of the EPSCoR program. “Without the formation of the EPSCoR program, I'm not sure these collaborations would have occurred, but because of it, we've already established some exciting new research directions. The future is very bright,” said Sparks.

Tom Hanson, assistant professor of marine and Earth studies at UD, said an EPSCoR lunch led to a seed grant he shared with materials scientists at UD. “Given our success there, we applied to the NSF Nanoscale Engineering Research program to get the grant that we are now working on,” Hanson said. “That grant, then, is a result of that one conversation at an EPSCoR lunch.”

Education is key

Other scientists noted the importance of sharing information with K-12 educators in the state. Harsh Bais, associate professor of plant and soil sciences at UD, who said EPSCoR has enhanced his publication record markedly in the past year, cited DBI Assistant Director Jeanette Miller's guidance in helping him translate his research for teachers. “With the help of Jeanette, we've been able to move our story from labs to K-12 schools and inspire students to study plant biology,” Bais said.

At Delaware Tech, the EPSCoR-funded “Pathways to the Future” program brings seventh- and eighth-graders to campus on “Science Saturday” and in the summer for a weeklong camp to familiarize them with science. (Information on EPSCoR outreach is available online, at [www.epscor.dbi.udel.edu/outreach/index.php]).

Kelli Martin, an education associate for science at the Delaware Department of Education, said that the EPSCoR grant, along with support from DuPont, has allowed 60-80 biology teachers to attend a workshop each October held at DBI. “Teachers observe firsthand the research going on in labs and attend symposium sessions that extend concepts learned in science to current research,” Martin said. Teachers also attend a 90-hour biology course facilitated by Bill Hall of the College of Marine and Earth Studies at UD. “K-12 science benefits greatly from the RII grant,” Martin said.

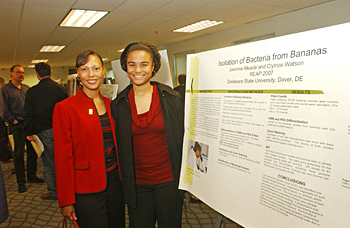

Undergraduate students who have had the opportunity to conduct research funded by EPSCoR have had their eyes opened to the collaborative research opportunities available to them in Delaware and beyond. Jasmine Meade, a Dover High School junior, presented her poster at the annual meeting, fielding questions from science professors.

“I love working with high school kids,” said Meade's adviser Clytrice Watson, an assistant professor in DSU's biology department, who studies microbial food safety and microbial interactions. Watson believes the best time to hook students in is when they're in high school. “Imagine telling your friends, 'I spent the summer out in Delaware Bay, tagging sharks.' I am so impressed with our high school students and look forward to involving more of them in research.”

Innovative environmental research

In Delaware, the collaborative research funded by EPSCoR targets the environmental stressors faced by the state's natural environment. According to Sparks, Delaware's major environmental challenges include marsh decline, fish kills and algal blooms, climate change, water quality, soil contamination and air quality. “Of course, all of these have an impact on human health and economic development,” Sparks said.

According to Sparks, future research efforts are quite focused. “We're now trying to look at subthemes of a broader theme that we're calling 'biogeochemical processes in the critical zone,'” Sparks said. “We're going to focus on particle transport and release, environmental observation and sensing, and microbe-metal interactions.”

The Center for Critical Zone Research, which Sparks directs, was established at UD in October 2006 as a spin-off of Delaware NSF-EPSCoR. “It brings together faculty, students and policymakers to discuss environmental issues and devise ways to reach out, network and help address some of the important issues we face in the state in terms of the environment,” Sparks said. “We obviously want to conduct world-class research focused on the Earth's life-sustaining, near-surface environment--the complex interactions of rock, soil, water, air and living organisms that regulate and populate the natural habitat.”

Other new initiatives resulting from EPSCoR include plans for a Center for Integrated Biological and Environmental Research (CIBER), the Science, Ethics and Public Policy Program (SEPP), the Ethics Resource Site, the Center for Spintronics and Biodetection (CSB), and the new NASA EPSCoR program. A major goal going forward is to expand center initiatives, said Karl Steiner, associate director of DBI and a co-principal investigator of the EPSCoR RII grant.

A major goal of EPSCoR is to help the state's economy, in addition to improving its natural environment. Delaware State University President Allen Sessoms said DSU is adding doctoral programs and relying on its partnerships with the UD, Wesley and Delaware Tech to ensure that research efforts in the state continue to grow. “There is great enthusiasm in the state for research,” Sessoms said.

David Weir, director of DBI, concurred, pointing out that Delaware's successful bid to keep the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca in the state was followed by the creation of DBI and the state's successful bid for EPSCoR status. “We went down to Washington, talked with NSF, and told them what we were doing. They supported our bid for EPSCoR status, and we won our grant and just submitted a second application,” said Weir.

Delaware Lt. Gov. John Carney said the best way to spur economic development in the state is to concentrate on scientific education and research. “The building of academic capacity is really important, but at the end of the day, it's about creating new businesses and jobs for the people in our state,” Carney said. “As the First State, we'd like to be first in science and innovation, and we'd like to be the first state to graduate from EPSCoR.” Carney chairs the Delaware Science and Technology Council, formed in 2006 to identify and advance critical initiatives in science and technology, and he cited the council as a positive outgrowth of EPSCoR.

Delaware EPSCoR's Research Infrastructure Improvement program has produced significant results. In the past three years, UD, DSU and Wesley brought six new faculty members on board, 48 papers were published and research teams were awarded 21 seed grants totaling nearly $4 million. The seed grants then catalyze new research.

Qiquan Wang, assistant professor of chemistry at DSU, said he published three papers in the past year and has another three in review, thanks to EPSCoR. He credits his funding with his ability to gather enough preliminary data to apply for additional grant monies. “I really appreciate the opportunity,” Wang said.

Keka Biswas of Wesley College is the newest EPSCoR faculty member and the first research faculty member at the college. “Without EPSCoR, it would not be possible for a small college like Wesley to conduct such research,” Biswas said.

For more information, visit [www.epscor.dbi.udel.edu].

By Katie Ginder-Vogel

Photos by Duane Perry