At present, the answers for parents of high-risk infants are few, according to James C. (Cole) Galloway, a University of Delaware associate professor of physical therapy and director of the Infant Motor Behavior Laboratory.

Galloway and coworkers hope to change that through a new five-year, $1.6 million National Institutes of Health grant, in which a multidisciplinary team will combine studies of learning and coordination with advanced brain imaging in infants born full term as well as those born at high risk for long term disability.

“High-risk infants may have brain lesions at birth. Parents of these infants want to know what those injuries mean in terms of their child's thinking, learning and moving,” Galloway said. “For physicians, therapists and nurses, this is a very difficult question. Because the infant brain has enormous capacity, some brain lesions do not result in significant developmental problems. In contrast, other seemingly minor lesions can result in notable problems later in childhood. We now have the tools and the team to begin to give clinicians and families some answers to this complex brain-behavior relationship.”

Galloway said the grant would enable the continuation of his group's research into learning and coordination among high-risk infants, and would link several laboratories and institutions.

In addition to Galloway's team, the project will include Mark E. Stanton, UD professor of psychology and expert in the developmental psychobiology of learning and memory, the leading-edge image processing facilities at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute, and the brain imaging and neonatal intensive care at area hospitals, including Christiana Care Health System.

“This is a groundbreaking project with many 'firsts,' including the first link of advanced brain imaging with early measures of learning and coordination in high-risk infants,” Galloway said. “We will follow our infants for a two-year period after birth in the hopes of using imaging and behavioral measures to predict the level of impairment later in childhood.”

The project will combine sophisticated imaging, including cranial ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, with two learning measures to better understand the brain-behavior relationship among the highest risk babies.

Galloway directs the UD Infant Motor Behavior Laboratory and his research team has been gathering data on learning impairments in preterm infants. Researchers there have been looking at differences in motor learning of very young infants born full term and preterm by observing how 90-day-old full term and preterm infants kick to move a toy mobile.

The results have shown that full term infants learned to make the mobile move within one session, whereas preterm infants did not learn despite having 12 sessions over six weeks. In addition, full term infants learned that to move the mobile, all that was needed was right leg kicking. Preterm infants kicked both legs the same amount throughout the study.

The researchers concluded that the full term infants adapted their kicking to move the mobile and retained the adaptation in their short-term memory, while the preterm infants showed no adaptation, suggesting a potential impairment of early motor learning or purposeful leg control. This lack of control, they believe, may reflect a general decrease in the ability of infants born preterm to use their limb movements to interact with their environment.

Stanton conducts research on a similar infant population but using an eye blink conditioning paradigm, a process in which an association is learned between the sound of a tone and a puff of air to the eyeball.

In the studies, infants hear a tone, receive a puff of air on the eye and blink. Gradually, they learn to blink in anticipation of the puff. The task makes it possible to analyze brain circuitry underlying associative learning and cognition, and Stanton's work has shown that preterm infants have difficulty in this regard.

Galloway stressed that a key to the project is its interdisciplinary nature. At UD, the project includes the physical therapy and psychology departments, the Pediatric Rehabilitation Clinic and DBI.

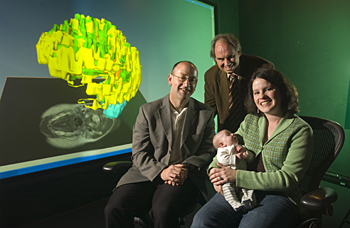

The laboratory testing will be paired with the latest in technology at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute. Karl Steiner, associate director of DBI, will use powerful computers to create three-dimensional models of infants' brains and area hospitals will provide magnetic resonance imaging.

“The brain imaging portion of this project is advanced and the learning and coordination measures are new to high risk infants,” Galloway said. “Our hope is to be able to generate a mosaic of brain and behavioral measures to provide clinicians and families a better understanding of the behavioral impact of early brain lesions.”

The results will provide the foundation by which the effects of early intensive rehabilitation intervention can be determined, Galloway said.

The study also will work with full term babies and Galloway said the team is actively recruiting “soon to be moms” in their third trimester to include their infants in the study.

Article by Neil Thomas

Photos by Duane Perry