Editor's note: This is one in a series of articles featuring UD polar scientists that will appear on UDaily during the International Polar Year. For a gateway to past and future articles, be sure to visit UD's polar research Web page at [www.udel.edu/research/polar].

11:22 a.m., June 1, 2007--David Kirchman has sailed among glaciers, walked with penguins, swum in the same icy waters as polar bears, and seen ice-covered mountains so majestic they've taken his breath away.

Kirchman, who holds the title of Maxwell P. and Mildred H. Harrington Professor of Marine Studies at UD, is a veteran of scientific research cruises in the freezing waters of both the Arctic and the Antarctic, with more exciting voyages ahead in the International Polar Year.

For nearly a month this past winter, Kirchman lived and worked aboard the 249-foot research and supply vessel Laurence M. Gould in the Southern Ocean off western Antarctica, near Palmer Station, one of three U.S. research stations on the frozen continent.

The research cruise was part of the National Science Foundation's Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Program, which is collecting data on a variety of ecosystems, ranging from forests to deserts, at more than two dozen research sites, primarily in the United States.

LTER research at the Palmer Station site focuses on the ocean ecosystem off Antarctica. It has been under way since 1990, and research cruises have been conducted annually along the Antarctic Peninsula since 1993.

Kirchman, an expert in marine microbiology, was invited to participate in the latest cruise by Hugh Ducklow, Glucksman Professor of Marine Science at the College of William and Mary, who is leading the Antarctic LTER project. The two scientists have been colleagues since they were doctoral students at Harvard more than 25 years ago.

One use of the long-term data collected in Antarctica is to document climate change and its impact on the ocean environment.

“There are already signs of it, such as the earlier melting of ice in the austral spring, and longer periods of open water,” Kirchman said. The “austral spring” is September and October in the Southern Hemisphere.

“Data on ice coverage and ice-dependent animals indicate that the climate is changing rapidly and dramatically in the Antarctic environment,” he said. “For example, Adelie penguins, which depend on ice, are decreasing around Palmer as the extent of ice coverage decreases. They are being replaced by other penguins that are less ice dependent.”

Kirchman got to see the flightless birds close-up during a visit to Torgersen Island, near Palmer Station. The island is home to a small colony of Adelies.

“Suffice it to say, penguins are very funny--and very smelly when in such large numbers,” Kirchman said. “They are much more graceful in water, where they look like small dolphins playing in the waves.”

Kirchman's role on the research cruise was to analyze the tiniest life at the base of the ocean's food chain--the microscopic plants and animals collectively referred to as “marine microbes”--and their impacts on the carbon cycle, a complex series of exchanges that occurs among the atmosphere, land and ocean.

The world's carbon cycle is based largely on carbon dioxide, one of several greenhouse gases in our atmosphere, so named for their ability to trap and absorb heat radiated from Earth as sun warms the planet.

While carbon dioxide occurs naturally in the atmosphere, certain human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels, can contribute to increased levels of the gas, strengthening the “greenhouse effect” and the subsequent heating up of the Earth.

“The ocean plays a major role in the carbon cycle,” Kirchman said.

For example, the carbon dioxide that you know as a gas in the atmosphere occurs in a dissolved form in the ocean. It is used by microscopic plants to make food during photosynthesis. As these microbes remove the carbon dioxide from seawater during photosynthesis, they release oxygen in the process.

“In fact, some scientists have estimated that marine microbes generate more than half the oxygen on Earth,” Kirchman noted.

While only a single cell in size, the microscopic inhabitants of the ocean are diverse and abundant. One-quarter teaspoon of seawater contains more than a million of these tiny organisms.

Throughout the 28-day Antarctic cruise, Kirchman helped collect and analyze seawater samples taken at 60 locations in the Southern Ocean. While some measurements of microbial activity were done aboard ship, the DNA analyses of the samples are now under way in Kirchman's lab at the Hugh R. Sharp Campus in Lewes. The samples were put on ice and shipped to Delaware at the end of the cruise.

“I usually worked in tennis shoes and a sweater during the cruise because nearly all of my work was done inside,” Kirchman said. “I would just run from one lab to another lab on deck, spending only a few seconds outside.

“I think this is one of the biggest misconceptions about Antarctica,” he added. “During the summer there, the temperatures are only around freezing. The wind is cold, and people working on the ship's deck certainly wear warm clothes. But otherwise, Antarctica in summer is like walking around in Delaware in January--at least during a normal, cold winter.”

Kirchman said the bigger challenge during the cruise was dealing with the ship's motion.“You have to be very careful that things don't go flying when the ship takes a roll,” he said. “The first few days are often bad as you and your scientific gear get used to the motion, but eventually you get used to it.”

Fortunately, the 24 hours of daylight during the Antarctic summer weren't too jarring.

“Our stateroom was completely dark when the portholes were covered,” Kirchman notes, “so the night crew might have appreciated the light more than me.”

And is often the case on research cruises, meals were the highlight of the day, and the “night.”

“The food was quite good, and with few exceptions, we had several choices, including dishes for vegetarians,” Kirchman said. “Only when we had really rough seas and some pots spilled over did we have just one choice for the main entree,” he says. “Since the ship operates 24/7, there is even a meal at midnight that we refer to as midnight rations, or 'midrats.'”

While the exercise room, library, sauna, TV room and computer (for checking thrice-daily e-mail transmissions) were all places to spend free time for the 46 people aboard the ship, viewing the Antarctic scenery took top billing when the ship was near shore.

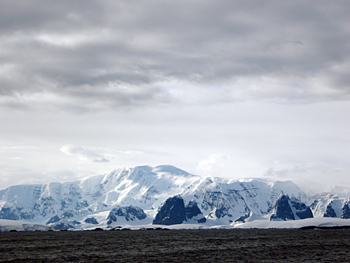

“I saw a lot of beautiful ice in the Arctic when I was there doing research last spring, but the scenery of this trip to Antarctica was breathtaking. The mountains and glaciers were absolutely incredible,” Kirchman said.

This was the second time Kirchman has conducted research in Antarctica--a decade ago, he participated in a research cruise aboard a different U.S. Antarctic Program ship, the 308-foot Nathaniel B. Palmer, in the Ross Sea, which is on “the other side” of the frozen continent.

During the past five years, he also has been on two of his UD laboratory's four research cruises in the Arctic, all aboard the U.S. Coast Guard's 420-foot icebreaker Healy.

It takes a little getting used to the noise and the stop-start motion of this Arctic vessel as it bangs its course through the ice, Kirchman said, but you eventually adjust as scientific studies start humming along.

Kirchman will be returning to the Arctic this summer--this time to conduct experiments at the Barrow Arctic Science Consortium's facilities in Barrow, Alaska's northernmost city, located 340 miles north of the Arctic Circle.While the Antarctic research is not directly linked to his Arctic work, Kirchman says he will be able to compare how the microbes from each environment adapt to life in perennially cold waters.

“We expect that the microbes and adaptations in the Arctic will be similar to those in Antarctic waters, but there are some crucial differences,” Kirchman said. “The biggest is that unlike in the Antarctic, the Arctic waters can be heavily influenced by rivers and other terrestrial sources of various materials.”

Reflecting on his polar journeys to date, Kirchman noted that during each expedition he has been reminded of the challenges that the legendary first polar explorers, such as Amundsen and Shackleton, faced.

“It is incredible to think of the first explorers sailing in ice-filled waters in wooden ships,” he said.

And the one thing that he most wants people to understand about polar research today is that humans have extended a much farther reach to the “ends of the Earth” than we realize.

“Antarctica is very forbidding and daunting, and it is hard to imagine that we could have any impact on it, being thousands of miles away,” Kirchman said. “But we do.”

Article by Tracey Bryant

Photos by Hugh Ducklow and David Kirchman