12:40 p.m., June 13, 2003--As “The Matrix Reloaded” rakes in millions at movie theatres nationwide, its predecessor, “The Matrix,” continues to be at the center of a debate that focuses on many classic and contemporary philosophical issues.

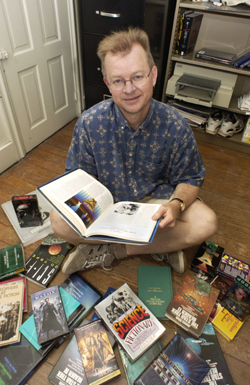

Among those participating in the dialogue are Richard Hanley, UD assistant professor of philosophy, whose article, “Reflections on the First Matrix,” appears in the “Philosophy Section” on the film’s web site at [http://whatisthematrix.warnerbros.com/].

|

| Richard Hanley, UD assistant professor of philosophy: “I am a firm believer in an appropriate popularizing of philosophy. My idea is let’s take these issues to the street.” |

The first “Matrix” features the adventures of a hacker named Neo, who eventually learns that all that he imagines to be real is merely a computer-generated illusion created by machines who use human beings as energy sources in much the same way the way we use batteries to power everything from calculators to computers.

The goal of the machines is to wipe out the existence of all free humans, whether inside or outside the matrix.

In the article Hanley, raises the question of what matters more, having free will or being happy in a “Matrix”-like world, where everything is an illusion? And, Hanley asks, when free will and human interaction collide—is happiness really possible?

“There is an analogy between the first `Matrix’ and the idea of what constitutes a happy existence for human beings,” Hanley said. “If you look at this from a Christian perspective, with God creating the world for a good purpose—you have to ask yourself the question of why there is so much suffering.”

Most people, when first asked what is most important to them, say they just want to be happy and enjoy the type of existence found in a “Matrix”-like world, Hanley said. However, when they consider the issue at depth, they nearly always make the opposite choice.

“When you ask people if they would want to exist in a state of blissful ignorance in a matrix, or in a the real world, with all that goes with it--they choose the latter,” Hanley said. “They say that happiness (as experienced in the matrix) is not a real choice. They opt for the real world.”

The problem, as raised by the character Morpheus in the “Matrix,” is how does one determine if one’s individual existence is real—and if so, whether it is the best sort of possible existence.

Hanley also explores the idea of heaven to see if free will and social interaction would be possible in what most Christians consider the ideal state of being.

“I wanted to look at the notion of heaven,” Hanley said. “I wanted an exploration of what constitutes the ultimate value.”

In “Part II” of his essay, Hanley writes that although the Christian idea of heaven “is far from a settled body of doctrine—there exists a general agreement among Christians that things beyond the Pearly Gates will be much different then they are here on Earth—at least as far as human beings are concerned.”

One of the problems with this ideal picture of celestial existence, Hanley notes, is that when people with free will interact with similar-minded individuals almost anything can happen—and not always for the best.

If this ideal of heaven is incompatible with the presence of free will, what can be said of the problems faced by the machines as they attempted to put together the illusionary world portrayed in the first “Matrix?”

These are some of the same problems that faced the builders of the first matrix—also envisioned as a perfect world, where suffering would be eliminated and all would be happiness, Hanley said. As the character Agent Smith said in the “Matrix,” “It was designed to be a perfect human world. It was a disaster.”

“Maybe the machines in the first matrix just fouled it up when they ran into the problem of trying to negotiate around the idea of free will,” Hanley said. “Maybe you can’t build a matrix and still have the option of free will.”

Not surprisingly, Hanley’s comments have generated a fair share of response, including e-mails and articles on web sites such as [http://www.faithandvalues.com/], where what Hanley said a fair and balanced response appeared with the title “What will heaven be like.”

“Most of the responses have been positive,” Hanley said. “A few individuals said I should mind my own business. I have learned through experience to respond politely to those types of messages.”

“Reflections on the First Matrix” is not Hanley’s first exploration into the philosophical and metaphysical issues found in mainstream science fiction venues. His 1997 book, “The Metaphysics of Star Trek,” caught the attention of David Chalmers, author of “The Conscious Mind: In Search A Fundamental Theory.” His article, “The Matrix and Metaphysics,” also appears on the philosophy pages of the “Matrix” web site.

“He liked my Star Trek book and suggested that I be used a contributor to the `Matrix Reloaded’ web site,” Hanley said.

Favorite science fiction movies for Hanley, who earned his doctorate in philosophy at the University of Maryland in College Park, include “Blade Runner,” “Starship Troopers,”

“The Matrix,” “12 Monkeys” and “Donnie Darko.”

Hanley, who teaches a course on the metaphysics of time travel “Time Travel,” said that an appropriate use of popular culture is to engage students in discussions of philosophical concepts.

“I try to introduce new students to the world of philosophy,” Hanley said, “through the use of a medium and a story that they are familiar with. This helps students to find new examples of the ideas that we have been discussing in the classroom.”

Although most of his research is concerned with themes of a scholarly nature, Hanley welcomes the challenge of responding to the philosophical and metaphysical issues posed by movies such as “The Matrix” and “Matrix Reloaded.”

“I am a firm believer in an appropriate popularizing of philosophy,” Hanley said. “My idea is let’s take these issues to the street. I invite those who are interested to come along with me.”

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photos by Kathy Atkinson

|