Abstract:

With the introduction of inexpensive and digital filmmaking alternatives a young generation of Cuban filmmakers is creating a distance from the centralized state ICAIC using non-theatrical distribution, and digital technology to change the audiovisual landscape. I explore how young filmmaker Aram Vidal has added another dimension to this generation creating critical films on Cuban identity and its diaspora from within Cuba and abroad. I argue that through films like Vidal’s this generation is re-defining what Anderson calls Cuba’s imaginary community to include a more fluid definition of Cuban identity, while also challenging the definition of film and the audiovisual field.

Key words: Cuba, young filmmakers/ nuevos realizadores, audiovisual field, Aram Vidal, Muestra Joven-ICAIC, Imagined community

****************************** |

I. Introduction:

In the opening minutes of Cuban film director Aram Vidal’s award-winning short documentary

De Generación (2007), a handful of twenty year-old Cubans individually share their thoughts on national identity, intimate frustrations with Cuban society, views on emigration, and beliefs on the future of the Cuban revolution as the camera registers the sights and sounds of downtown Havana. Two years later in his documentary entitled

Ex generación (2009) another group of young Cubans reflect on their collective identity, what it is that defines their Cubanness, their views on the island’s transition, and the future of the nation. After three more years, Vidal, in his documentary

Bubbles Beat (2012), explores yet another group of struggling twenty year-olds facing similar challenges to define their generation lost in a previously promised national dream while surrounded by unemployment and looming student loans.

There is one large difference between Vidal’s three short documentaries: location. He made

De Generación in Cuba focusing on Cuban youth,

Ex generación in Mexico focusing on young people from the Cuban diaspora living in Mexico, and

Bubbles Beat in the US on their non-Cuban US counterparts. Each of these three films premiered and competed in the

Muestra Joven [Young Showcase] in Havana, Cuba even in the physical absence of the filmmaker Aram Vidal from the island. These films represent a new generation of filmmakers and films not fixed solely in Cuba. Instead these artists are in contact with others sharing their works with people off the island, while others create from the diaspora and distribute their films to those on the island. The films themselves represent this exchange that is now part of the contemporary young filmmakers’ reality through digital technology, and informal distribution beyond the complete control of the Cuban state. In this way Vidal and his works, like others of his generation, echo the title of the New York University November 4-10, 2013 conference entitled “Cubans in Movement: Toward a New Civil Society”. In his introduction to the conference Antonio José Ponte explains that “Es hora ya de que vayamos pensando en cifrar las esperanzas en la propia decisión de la ciudadanía cubana en la confirmación de una ciudadanía que sea capaz de presionar sobre las autoridades y de ponerse en movimiento”. This new generation of filmmakers and their films form part of the “ciudadanía”that Ponte reflects on whose works are literally “en movimiento” in novel ways previously impossible in and outside of Cuba.

Vidal is just one voice in a sea of critical young filmmakers known as

nuevos realizadores [new filmmakers] that are redefining Cuban cinema. This is a loosely connected group of filmmakers between 20 and 35 years of age that has taken shape since the year 2000, and includes Aram Vidal, Miguel Coyula, Karel Ducasse, Ariagna Fajardo, Heidi Hassam and Carlos Lechuga, among many others. I focus this article specifically on Vidal for two reasons. The first is that the content of his short works,

De Generación, and

Ex generación, creates a critical dialogue that capture his generation’s struggles to define itself in a globalized Cuba in transition. Secondly, beyond the content of the films, his filmmaking process, current residency in Mexico, continued exhibition of his works in Cuba, and use of digital distribution explicitly test previously rigid definitions of national identity.

I closely analyze Vidal’s

De Generación and

Ex generación to illustrate a selection of the practices of the Cuban

nuevos realizadores. Through these two works in particular I show how this new generation of Cuban filmmakers living both on and off the island, using digital technology to create and distribute their works, have established an artistic presence within and beyond Cuba that previously had been close to impossible during the past five decades of the Revolution. With Vidal’s documentaries we can see that this generation is challenging the limits of the term ‘Cuban’ since a number of the award-winning

nuevos realizadores including Aram Vidal, Heidi Hassam, Sandra Gómez, and Alina Rodriguez Abreu live outside of Cuba yet continue to have an artistic presence on the island to varying degrees. Vidal lives in Mexico, Hassam in Spain, Gómez in Switzerland, and Rodríguez Abreu in the U.S. This ability to remain in contact with Cuba, and in some cases participate in the annual

Muestra Joven from the diaspora, is a relatively new idea that has begun to create a more porous concept of national identity and with even the possibility of ‘being Cuban’ beyond the physical borders of the country. Vidal’s mobility across national borders breaks with the decades-long tradition of becoming an outcast/outsider after leaving the country. That is, he is still present though he does not live on the island.

What is also remarkable about this generation, the

nuevos realizadores is that they do not depend entirely on the centralized

Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (the Cuban state’s film institution) for resources. Instead they distribute their works domestically and internationally on flash drives, YouTube, Vimeo, and inexpensive copied DVDs creating an informal, albeit ad hoc, system that reflects a new type of filmmaker and audience that are now traveling in multiple directions both on and away from the island. Through the audiovisual field, these filmmakers are opening a space to reconfigure that which Benedict Anderson calls the “imagined community,” which in Revolutionary Cuban film had been officially recognized as a set identity bound by the island’s physical borders, and by the ICAIC. With new themes and practices these filmmakers contribute to the audiovisual landscape that has had an active role in shaping the imagined community from the beginning of the Cuban Revolution.

Witnessing this shift in re-defining the audiovisual landscape and in turn the imagined community, a select group of intellectuals in Cuba and the United States has actively followed this prolific generation of filmmakers. Cuban critics such as Gustavo Arcos Fernández, Danae Carbonell Diéguez, Marta Díaz Fernández, and Juan Antonio García Borreroong with US-based critics such as Sujatha Fernandes, Alexandra Halkin, and Ann Marie Stock, suggest that this generation of artists is making some of the freshest and most inventive Cuban contemporary works. As Fernandes and Halkin write, “[t]hese young filmmakers are teaching themselves how to tell stories that resonate with the Cuban public and to generate internal discussions to improve conditions”(20). These filmmakers are not only creating works with limited resources, but also are using said works to provoke reaction in their domestic and international audiences.

While over the past decade and a half this generation has created a space beyond the Cuban state, their work still faces many challenges. In January 2013, Victoria Burnett reported on this generation of filmmakers in a

New York Times article to explore their obstacles and their impact on the Cuban audiovisual landscape. Burnett writes, “[a]round the country, Cubans are making features, shorts, documentaries and animated works often with little more than a couple of friends and some inexpensive equipment--and little input from the state-supported Cuban Institute of Cinematic Art and Industry.” In Cuba’s historically centralized film context, they are considered a subversive generation of filmmakers that exist beyond the state’s control of approved subjects and themes. Burnett quotes the young Cuban filmmaker Karel Ducasse, ‘“The state has become afraid of digital media…They know anything can be passed around the island.’” Ducasse’s work is proof of the subversive power of these digital films. One of his documentaries,

Zonas de silencio (2007), is a poignant critique of official censorship in contemporary Cuba. While controversial, Ducasse’s film won the Special Prize of the Documentary Jury from the Cine Pobre, Gibara Festival in Cuba. Many in Cuba have seen the film, and the US non-profit organization Americas Media Initiative distributes the film to schools and institutions outside of Cuba. In other words, this generation is not only subversive for making these films, but their works are also provoking debate, and showing in spaces outside of the state.

Given the beyond-the-state workings, one could categorize this generation as entirely independent of the Cuban state. Film critic Manual Zayas explains that “digital filmmaking is completely beyond the [Cuban] government’s control…What is clear is that independent filmmaking represents, despite the government, the future and the hope of salvation in Cuban cinema.” While Zayas’ work echoes the fact that this generation of filmmakers represents a step towards independent film, I cannot completely agree with his reading that the

nuevos realizadores are

entirely independent of the Cuban state. To indicate the peculiar relationship with the state Stock coins the term “street filmmaking” to reflect the nuevos realizadores’ space in-between the state and independent filmmaking (15). She explains that it is difficult for these young filmmakers to be completely separate in Cuba due to their nearly non-existent budgets. Thus Stock argues that many of these filmmakers rely on a web of friends, acquaintances, and resources directly connected to state-sponsored institutions to make their films (21). Also adding to the complex identity of these filmmakers is that this generation does not fit into a previously established Pro-Castro vs. Anti-Castro dissident Cuban binary. Instead these filmmakers stem from a generation of young people who have a different relationship with the Cuban state who often look to criticize their society in hopes to make Cuba a better place without abandoning all values of their system. Stock explains that “Street Filmmakers do not tend to see themselves as part of the collective Revolutionary project in the way that their elders did. Born after 1959, they are inheritors of the Cuban Revolution rather than its architects…their sense of citizenship and national identity differs dramatically from that of their parents’ and grandparents’ generations” (16). While their family members may have contributed to fighting for and defending the Revolution and have experienced the national euphoria of the early years, the young generation do not share in this euphoria, nor do they have a unified collective identity.

Intentionally or not, another difference with this generation is that they have also challenged the island’s geographical exclusions to reconfigure a concept of nationality by creating a more inclusive definition of Cuba. By remaining in contact and exchange with their peers who have left the island through social media and participating in the

Muestra Joven annual film festival some of these Cuban filmmakers “in movement” have created a space that also allows for works made from the diaspora that are still considered Cuban. Thus filmmakers continue to share films and contribute to the island dialogue regardless of their physical location. This is a shift in the imagined community and shows an expanding re-definition of Cuban identity. Given Cuba’s historical rejection of the diaspora, and rigid concept of Cubanness based on residency on the island, the ability to participate and continue with a level of presence on the island shows a challenge to being Cuban from the diaspora.

While this inclusion is happening in the digital world of the

nuevos realizadores, there is a need for film criticism and the ICAIC to reflect this changing reality. Cuban film critic Juan Antonio García Borrero explains that academia needs to rethink categorizing films or a film’s origins to provide a more inclusive space for Cubans and their works beyond the island. According to García Borrero rethinking these categories is a way to challenge and amplify the imagined community. While a conversation to redefine the limits of what is considered ‘Cuban film’ has formed, this generation is also beginning to challenge the previously rigid definition of the term ‘film’. García Borrero explains that the term ‘film’ during the decades of revolutionary Cuba has been directly equated with works from the ICAIC. The centralized ICAIC has determined content, production, distribution, and legitimation of film material throughout the island since its establishment in 1959 it being one of the initial investments made upon the triumph of the Revolution. Independent works made outside of the ICAIC have historically been censored in Cuba since the famous

P.M. affair in 1961 (Lopez)

1.

P.M, the short independent film on nightlife in Havana, made independently from the ICAIC, portraying a non-approved version of revolutionary Cuba, only six weeks after the Bay of Pigs Invasion, resulted in explicit censorship, and Fidel’s famous 1961 speech “Palabras a los intelectuales,” making clear that film, and art in general, needed to serve the ideology of the Revolution. Because of this state dictum and limited space beyond the state, filmmakers have continually struggled over the past five decades to maintain a critical stance in their works from within the ICAIC. Also during the first forty years of the Revolution, due to the high prices of raw film stock and its scarcity, a select group of filmmakers from the ICAIC were among the few with access to resources to make films in Cuba, therefore recognized films made in Cuba were for the most part ICAIC films. Given the association of the term ‘film’ with ICAIC filmmaking, García Borrero poses to use the term ‘audiovisual’ to replace ‘film’. He argues that the ‘audiovisual’ field is inclusive of the works made beyond the ICAIC to provide a space for a larger concept of works including those of the young generation. This term is especially appropriate when considering that these young filmmakers do not use film at all, but rather digital technologies from the audiovisual field to make and distribute their works. The ‘films’ from this generation, at times created from the diaspora (and in the case of Vidal, using digital technologies and relying on non-theatrical distribution) expose the limitations of terms such as “Cuban”, “film”, “industry” and the established imagined community.

II. The ICAIC and the Muestra Joven:

The boom in street-filmmaking, and the explosion of young Cuban voices in digital film resonates with a mosaic of changes in Cuban history. These changes in part resulted from the previous decade’s austerity measures, economic crisis, and new forms of artistic possibility stemming from the pain of the 1990s in Cuba known as the Special Period in Time of Peace, considered to have started in 1991 until c.2000. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, film was almost entirely considered a state-run project. The lack of resources available during the Special Period forced Cuba to depend on co-production to keep filmmaking afloat on the island. These looming economic challenges coincided with an international shift in filmmaking technology to include inexpensive personal and later digital options. The

nuevos realizadores emerged in the face of these social, economic, and political changes, and contributed to this transition.

In a climate distinguished by a changing revolution and paired with the sentiments of disenchantment with the political project, this new generation of filmmakers uses the annual

Muestra Joven, a six-day film festival, to present, discuss, and critique these works. The showcase also includes film screenings, master workshops, roundtables on film policy, classes on pitching new projects, and open debates on filmmaking to name a few of the events from the

Muestras. The 2014

Muestra took place from April 1-6, in the Vedado section of Havana at the Fresa y Chocolate Cultural Center, with film screenings and events at the Charles Chaplin Theater, the 23 y 12 Theater, and the ICAIC.

Since its beginnings in 2000, the

Muestra Joven has served as a space for these works to gain visibility, albeit only during the limited days of the annual showcase. In an interview, Aram Vidal cites the first

Muestra Joven as one of the determining factors that inspired him to participate in filmmaking (Farrell 39). Vidal has since participated in a number of

Muestra Joven festivals from Cuba and abroad, and is reaching the under 35 age-limit of the event. Since inspiring Vidal in its first festival, the

Muestra has evolved, bringing with it name changes thus complicating research on the subject. It was previously known as the

Muestra Nacional del Audiovisual Joven, renamed the

Muestra Nacional de Nuevos realizadores, again renamed the

Muestra de Nuevos realizadores, renamed the

Muestra Nuevos realizadores and since renamed with its current full title

Muestra Joven ICAIC. This final name further supports Stock’s proposal to consider the

nuevos realizadores as “street filmmakers” instead of independent filmmakers (15) because while the ICAIC does not have complete control over the digitally made films, the ICAIC does sponsor the annual

Muestra Joven ICAIC showcase. The ICAIC’s role as sponsor of this beyond-the-state film festival exemplifies that this generation is still loosely connected to the state. Beyond the

Muestra, a chosen few then compete in the International Festival of the New Latin American Cinema in Havana, and more recently they have also shown in the Havana Film Festival in New York in April 2014, to name a few of the possible venues for their films. In addition, a few filmmakers from this generation distribute their work to universities and individuals through the Vermont-based non-profit organization, Americas Media Initiative.

Despite the brevity and limitations of the

Muestra, pervading role of the ICAIC, and lack of venues for these works, Vidal is one of many filmmakers that has earned recognition and grown with the showcase both within Cuba and beyond. His film

De Generación, won the 2007 annual

Muestra in the category of Best Documentary. Also in 2007, the Cuban Film Press Association chose Vidal’s film as one of the top five documentaries screened in Cuba in 2007 on Cuban television and it subsequently won the Santiago Álvarez in Memorium Film Festival in 2008. Vidal’s later award-winning digital film

Ex generación made its debut at the annual

Muestra.

Bubbles Beat also made its debut at the

Muestra while Vidal was living in Mexico where he continues to reside. In this article, I will limit my analysis to

De Generación and

Ex generación since these two films are exemplary of a selection of the reoccurring themes in the works of many of the

nuevos realizadores. Also, these two films in particular create a type of digital dialogue between Cubans on the island now connected with their international peers, and a new face of the Cuban diaspora in contact with the island.

III. De Generación:

The film,

De Generación (2007), officially translated as

Off Generation, is subtitled in English and is available for viewing on YouTube. Through individual testimonies, the camera registers the hopes, worries, and struggles of six Cubans in various parts of Havana from the privacy of living rooms to rooftops overlooking the city. From the film’s first images, we are reminded of Cuba’s idiosyncrasies, its Soviet past, with traces of its complex relationship with the United States, all of which contribute to Cuba’s present mosaic that each of the Cuban individuals use to interpret their realities. Even before the title screen, the camera establishes this intricate political history and this uniquely Cuban context serves as a backdrop to the film.

As the film opens, the audience sees stick figure drawings in white on a black screen. The images are of military tanks rolling in under a bright sun. The camera quickly switches to another image of smiling stick figures on makeshift rafts under a Cuban flag. Finally there is a simple drawing of houses on a street. The street then cracks and a single flower turns towards the other side of the street, as a hammer and sickle appear. The allusion to the divided Cuban population is hard to miss coupled with Cuba’s Soviet past placing this intimate film within Cuba’s revolutionary context.

|

Opening image of divided street. (De Generación 2007) |

While the film is not explicitly political, these first black and white images silently remind the audience that these key moments in Cuba’s history are omnipresent in the nation’s current reality.

The drawings culminate with the title De Generación appearing in white letters on a simple black background. At a closer look the letters of the film’s title also embody Cuba’s past and present. The letters ‘n’, ‘e’ and ‘r’ appear backwards, reminiscent of the Cyrillic alphabet, while the ‘o’ in the title is accented with Nike’s trademark “Swoosh”. The script reflects Cuba’s complicated history where the Soviet influences share the screen with the presence of US capitalism, materialism, and imported goods.

|

Title screen. (De Generación 2007) |

Beneath the title is the English translation “Off Generation,” alluding to the film’s speakers and their struggle to define their generation. Another possible translation of the title is “Deterioration” from the Spanish verb “degenerar” to deteriorate. This translation points to a consistent tension throughout the film as to whether it is the young generation that is “Off” and not coming together in a collective struggle as previous generations of the Revolution, or if it is the Revolution itself that has deteriorated and fallen apart.

After the title screen, the camera focuses on a fishbowl view looking down onto Havana’s worn buildings. The camera then zooms in on the asphalt of an empty street while a few bikes pass as a young man begins to share thoughts on his generation. The speaker explains, “Me parece que entre la generación que nos ha procedido de nuestros padres y la de nosotros, hay bastante cambios. Yo pienso que en definitiva los sueños son un poco los mismos”. The camera changes to focus on another young Cuban man in his twenties explaining, “Ellos [the previous generation] tienen un background de todo el proceso de los últimos cuarenta años…que les da…muchos elementos para valorar, pero yo pienso que nosotros tenemos muchísimo menos prejuicio para valorar nuestro momento. Y eso abre el camino y abre espacio para que entre luz”. As each of the individuals separately struggle to define their generation’s place in comparison to those of the past, the camera follows each of these speakers in different spaces further highlighting them as individuals, instead of the non-personalized collective spirit of their parents’ generation. They are not the idealized men or women of the Cuban Revolution, instead each provides a unique view of their generation reflecting the age of Cuba in transition.

As these individuals remark on their generation, some voices yearn for a collective past or struggle. On a rooftop looking down onto Havana, one young man explains:

| Yo veo mi generación, digamos que…menos atrevida que la generación que nos antecedió…la generación que nos antecedió yo creo que se enfrentó con más firmeza cosas que le molestaban, un poco que cerraban su paso ante la vida… más decidida para enfrentar la barrera. |

He voices a level of nostalgia for a generation that he was not a part of, but that had come together to accomplish what became the Revolution. This young man highlights that while the Cuban Revolution continues, the Cuban youth have doubts and questions similar to their counterparts in different parts of the world regardless of Cuba’s national project. In a search of a collective identity, it could be the breakdown of a single collective identity and spirit that embodies the generation. This possible definition points to another revolution or change, breaking with the past narrative.

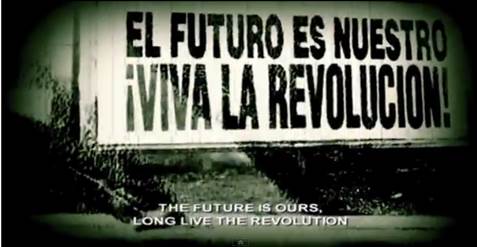

As this speaker explains that his generation is not inspired to come together, and create something as previous generations had done, the camera pans to show the lingering past revolutionary narrative hovering over Havana celebrating a particular identity. The billboards covered with the official discourse are in stark contrast with the speaker’s doubts. He finishes his thought while the camera displays the slogans of the Revolution, as a nostalgic instrumental lullaby plays in the background.

|

Billboards shot. (De Generación 2007) |

The camera centers on the numerous billboards in Havana with revolutionary sayings and public service announcements including the one above that reads, “The future is ours. Long Live the Revolution!” Through the use of the absolute possessive pronoun “ours”, the message highlights a shared and collective identity. The next frame shows, “Save: Only Consume what is Necessary”, and finally “What’s Ours is Ours”. The revolutionary slogans that the camera registers in sepia appear to have expired. The young people do not reflect this same collective spirit. With a return to a young speaker, the lullaby ends, and the camera returns to vibrant colors breaking with the sepia slogan images reminding the audience of Cuba’s present idiosyncrasies.

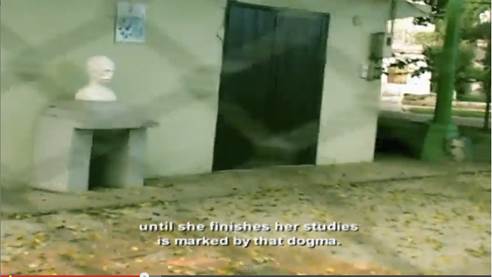

One speaker sitting in a park explains that there is a ubiquitous political dogma imposed to support “the process”. As the young woman explains how the dogma is everywhere from the minute a young child learns to read to the messages on television, the camera shows the presence of the said dogma in a subtle way by focusing on an empty school playground surrounded by a chain link fence with a bust of the national hero, José Martí. With this image, the camera registers the dogma beyond the explicit billboards but also within the educational system and the narrative of the country’s heroes.

|

José Martí bust in school playground. (De Generación 2007) |

Just as the audience is ready to highlight socialism as the culprit of the confusion of this generation, and the omnipresence of dogma, one young Cuban woman is filmed seated in her house explaining that Cubans are too materialistic, “Nosotros tenemos el síndrome del materialismo. Tenemos el síndrome de que las ideas no repartieron lo que esperábamos…entonces nos hemos virado a la parte más concreta de la existencia”

|

Cuban woman discussing materialism. (De Generación 2007) |

The materialism that this speaker criticizes is in contrasts with the past five decades of socialism, dogma, the US Embargo on Cuba, and the omnipresent billboards promoting austerity.

Unemployment and the inability to earn money contribute to the propensity for materialism, and are grand obstacles for many of the interviewees, who recognize that regardless of the socialist ideals of the Revolution money “funciona como pasaporte para moverte.” As the speakers discuss the limitations of employment, one young man explains that economic problems breed individualism, “hay una propensión al individualismo…cada cual…está preocupado por lo suyo y por salir adelante a su manera”. As he explains this tendency towards individualism, we begin to hear the sounds of marching boots. These boots echo the famous arrival of Fidel Castro and his troops to Havana in 1959 marking the Triumph of the Revolution. The sounds of the marching boots drown out all other sounds as the camera travels through Havana’s streets, much like the troops did years before. However, this time, the images that the camera shows accompanying the sounds of the marching boots are upside down.

|

Upside down image of Havana. (De Generación 2007) |

The inverted images with the noise of the boots underline that this individualistic reality is in deep contrast with the original ideals of the Revolution. The Revolution may have produced the opposite outcome of its objective.

With these critiques the film still does not reflect a complete lack of hopelessness about the future of Cuba, but rather the diversity of thought, and a refusal of a single imposed narrative. This generation has a more permeable identity with elements from the past and the globalized present that views critique as a necessary part of a reflective life. The narration in this documentary hints at the challenges to the singular official narrative, with speakers talking directly to the camera with their explicit subjectivity. The camera surveys the face of each speaker who becomes a unique subject in this film far from the authorless statements of the revolution. In this way, if a common voice or narrative was the strength of the past decades of the Revolution, in this documentary we see various voices, subjectivity, and individual ideas about the Revolution.

The camera further registers the idiosyncrasies of the contemporary messages covering the walls and billboards of Havana. Advertisements for new products share spaces with revolutionary messages calling for austerity. As the camera pans the streets of downtown Havana, focusing on advertisements on trucks and signs for new fast food businesses, voices of radio advertisements for Romeo y Julieta cigarettes accompany the product images, before the radio switches to announce news about ETA political prisoners in Spain.

|

Image of advertisement on truck in Havana. (De Generación 2007) |

The film further highlights how the revolution’s over fifty year old billboards share the cityscape with advertisements for the latest products, and international news. These conflicting messages coexist in today’s Cuba despite the original ideology or revolutionary billboard messages. The camera thus takes an inventory to document how today’s generation is confronted with conflicting narratives, different from the previous Cuban realities when supported by the Soviet Union.

As the camera returns to the interviews with the individual Cubans, one young man shares that he is tired of Cuba’s blinding sun and would like to see the cloudy days of France. He sits on the roof deck of a building overlooking Havana as he stares into the sun, with Ray Ban sunglasses and an Argentine soccer jersey. His eyewear and clothing are further proof of Cuba’s connection with life beyond the island’s limits.

|

Ray Ban glasses. (De Generación 2007) |

These products serve as reminders of Cuba’s place in a globalized economy. With imported products comes the ever-present Cuban topic of life beyond Cuba: travel, and emigration, while the inability to travel internationally remains a frustration for many of the speakers. As the camera focuses on the face of one Cuban man as he looks out through the slats of a window he explains,“Me cuesta un poco hablar de este tema…La cuestión de la inmigración nos ha dolido un poco y ver que el futuro de tu país solamente digamos que está en un marco donde lo único que puedas ver sea posibilidad de inmigrar…es bastante triste”.

|

Talking about leaving and travel. (De Generación 2007)

|

Four of the interviewees speak separately about travel and immigration, sharing a desire to travel, but not expressing that they would like to leave Cuba. Instead leaving and emigration hang like a cloud over these Cuban speakers as they contemplate their futures.

While questioning everything from their generation such as the meaning of the word ‘revolution’, materialism, and emigration, the short film leaves the audience with a hint of hope. The last interviewee laughs while seated on the ruins of a building in an abandoned park; he explains “somos parte…es bodrio el pastiche éste pero es lo que tenemos…suena fatalista pero, na’ eso se arregla también”; and then he stops talking and smiles at the camera. His words echo a tension between criticism and belonging amidst the deteriorating ruins of the park where he sits as he considers his generation.

The closing credits of the film are accompanied by the music of the highly critical, and at times censored, Cuban rap group, los Aldeanos. As the rappers share their criticism of Cuba’s official discourse, the camera shows the film’s credits imbedded in Chiclet, Nestle, and Brach candy wrappers. The camera scans the names that are glued to the pages of a book covering the book’s printed words. Between rappers and wrappers, the film positions this generation of Cuba at a crossroads between revolutionary discourse, isolationism, materialism, and globalization.

Through the natural lighting and intimate testimonies, these young people share with the camera on a personal level without falling into the all-too-common binary of pro-revolution vs. dissidence dynamic. In the search for a common cause or a united voice, the film uncovers many voices and concludes with more questions than answers on what it is that defines today’s youth in Cuba, or what makes something Cuban in a globalized world of advertisements, materialism, and the looming option to illegally or legally emigrate to explore a world beyond Cuba.

IV. Ex generación:

The next Vidal film Ex Generación serves as a form of sequel to De Generación, exploring the lives of another six young Cubans who have emigrated. They share their own stories about leaving the island, their lives in Mexico, conditions they feel would be necessary to return to Cuba, and their Cuban identity as members of the diaspora. To make this short documentary, Vidal visited Mexico to film these testimonies while he was still living in Cuba. Vidal won funding from the Mexican Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes to create the film, and upon its screening he also won a special mention and documentary prize from the Asociación Hermanos Sainz in Cuba. Here Vidal examines the reasons why these young Cubans left the island, a topic that often remains riddled with political discourse in film and literary representations. As art mirrors life, Vidal later became a Cuban living in Mexico, personally experiencing many of the speakers’ stories.

The film’s title Ex generación, or Ex generation, refers to a generation that previously existed and no longer does, as if Cuban identity were directly linked to a physical presence on the island. Upon emigrating, Cubans have faced a form of an identity abyss, consisting of years of official mistreatment by the Cuban government. For example the Cuban government has referred to emigrants as gusanos [worms] for having abandoned the country. This treatment, like many aspects of Cuba, is in transition, and works such as Vidal’s Ex generación, and social media itself have contributed to this mentality shift recognizing the possibility of being Cuban off the island. Regardless of decades of official discourse, the speakers in this film explain that their decision to leave Cuba has not erased their Cuban identity. Instead many of the speakers expand upon the difficulties of leaving, and how it has left a mark on their Cuban identity.

In the first images of the film, the camera opens with the traffic of Mexico City as cars slowly navigate the congested highway, followed by a moving train, and the looming advertisements that are a trope in Vidal’s work. The opening images of the film immediately establish the theme--people in movement, outside of their native Cuba.

|

Traffic in Mexico City. (Ex Generación 2009) |

These images of traffic packed highways, and urban light rail, and the cityscape are in direct contrast with the deteriorating empty asphalt streets of Havana from the opening scenes of De Generación.

Similar to De Generación, the camera gives a panorama of the speakers’ new environment, followed by close ups, as each speaker tells his or her story personalizing the politicized act of emigration. The speakers represent a range of experiences including a professional ballet dancer, a public health worker, a Mexican-Cuban, and a nuclear physicist to name a few. The speakers highlight exactly what pushed them to leave the island: including economic reasons, career opportunities, a need to provide for their families, or a desire to express themselves freely.

The camera focuses on the nuclear physicist as he states that while it was difficult to decide to leave Cuba, the professional possibilities on the island were slim. As he speaks, the camera shows a Mexican billboard advertising home supplies, with the words “Los grandes logros de la vida, adquieren sentido en casa”. This message is in contrast with the words of the physicist as he explains that it did not make sense for him to stay home in Cuba. The modern billboard advertisement is also in contrast with the sepia revolutionary messages plastered on the billboards in De Generación, yet both these billboards in Mexico and those of De Generación reflect the competing external messages that surround the individuals distant from their daily realities.

|

Billboard in Mexico. (Ex Generación 2009) |

After the physicist, the camera travels to the face of a young woman telling her particular story of living a life between Mexico and Cuba with her Mexican mother and Cuban father. She left Cuba for her career and remarked that her first full year in Mexico was horrible, “fue un año espantoso.” Although she was the most prepared of all the speakers in terms of life off the island, having been to Mexico previously, she still struggled with the transition.

While the camera travels outside in search of another interviewee, a young Cuban woman discusses that the majority of the people that leave are “la gente joven,” because they need to “decir cosas” and “la salida es salir. No te están dejando con muchas opciones.” With this reflection on the fact that often times those that leave are young people, we are reminded of the looming topic of leaving Cuba that the young people contemplate in the final scenes of De Generación. For many of the young people in De Generación, leaving the island might be the only feasible option that would grant them the coveted opportunity to travel freely. While this is the reality for many young Cubans, the camera captures her story as a unique subject and not merely a national statistic.

After discussing leaving Cuba the next question the speakers struggle with is that of finding ‘home’. The camera zooms in on one speaker as he explains that upon returning to Mexico after a visit to Cuba, he realized that Mexico had become his home. While Mexico has replaced Cuba for one man, Cuba remains present for others. For example, while the physicist adamantly speaks about his decision to leave Cuba, the camera begins to zoom in on his desk. The screen saver on his computer is a picture of el Malecón, and a book on Cuba rests against his computer. While his words show that he has come to terms with his decision, the camera captures the items on his desk that prove that Cuba is not far from his thoughts.

|

Image of desk in Mexico. (Ex Generación 2009)

|

This image suggests an overreaching question in this film about being Cuban outside of Cuba. The possibility of maintaining their Cuban identity is a topic that lingers over many of the speakers given the strict political and cultural definitions throughout the Revolution of being Cuban in direct association with living on the island. The physicist explains that it does not matter where a Cuban is living, there will always be a connection. This mentality differs from decades of official and social rigid definitions of Cubanness and reflects a transitioning mentality in terms of identity.

The second half of the film focuses primarily on exploring the question of the speakers’ Cuban identity, and how the government should treat them as Cubans living off the island. One speaker explains:

| no nos puedes culpar a los que estamos emigrando…no nos deben dejar de ver también como lo que somos cubanos también que estamos en este momento fuera…podemos regresar pero aparte podemos ser tu hijo, tu padre, tu hermano o tú mismo…no es excepcional, es algo natural. |

The speaker makes reference to the official treatment over five decades of those who have abandoned the country. While the Cuban government has recently changed its treatment of some Cubans who have emigrated, making it possible to return to the country, one speaker explains that the Cubans who have left still are not received with open arms by the government and often face entrance fees upon arriving to the country. As the speaker tells the camera, that those who leave could include anyone, the film appears to create a dialogue with the final images of De Generación as four of the six speakers contemplate leaving Cuba. They are not the demonized people that have been ostracized by the state instead they could be any Cuban.

Once having left, a very real concern and challenge that faces an emigrant is the question of returning. The ballet dancer observes how many of his Mexican friends celebrate the arrival of their emigrant families while in Cuba, for this speaker, this is not the case. He explains

| No sé por qué en Cuba se sigue satanizando al emigrante…porque …siento que ellos están tratando de hacer ver que en Cuba todo esté bien y que fuera de Cuba es todo un caos y entonces vamos a castigar a todo aquel que se vaya de Cuba. Hasta que las prioridades no cambien y no se vea al migrante o a la persona que se va de Cuba como un desertor como un apátrida, como un gusano, o una gente que abandonó el país no se vea de esta manera…no va a cambiar. |

While filmmakers such as Vidal, and many from his generation, have embraced Cuban identity on and off the island, the young dancer’s words underline that the mentality of punishing or blaming the ‘deserters’ remains.

Similar to the concluding tone of Vidal’s De Generación, the physicist’s final words are optimistic about change in Cuba and about the Cubanness of those living abroad. He explains that Cubans abroad are still Cuban, who for now, live outside of their country. He remains hopeful, for while it does not make sense to live in Cuba today, the tough transition that Cuba currently faces cannot last forever, and Cuba will have better “luck” in the future.

As the film concludes, the screen becomes black with the sentence “Cada año treinta mil cubanos abandonan la isla definitivamente”, followed by the sentence “más de la mitad de los emigrantes cubanos son menores de 35 años”. This reminds the audience that while the speakers have finished telling their own stories, there are entire young generations of Cubans in movement, whose voices have not been heard, and who contribute to the Cuban national identity from wherever they may reside. This final message alludes to a connection with Vidal’s previous film De Generaciónas where the speakers struggled to define their generation. Emigration and Immigration may be part of the defining characteristics of the contemporary young generation, or being Cuban beyond Cuba as well as the fragmented multiple personal narratives rather than a single collective voice. As the credits roll with the LaTour’s song “Otro amanecer” and black and white images of Havana, there is both a complex nostalgia for Cuba and these stories in movement, that are representative of many contemporary Cubans, especially those of the younger generation. Through works such as Vidal’s, these speakers demonstrate that they too make up a part of the nation’s identity, and contribute to the voices represented in the young audiovisual field now available for streaming on YouTube.

These films are in dialogue with each other. The young people in De Generación contemplate leaving and living off the island, and Ex generación follows Cubans that do seek a life off the island focusing on this young diaspora in Mexico, a country that has had fairly positive relations with Cuba. Ex generacións hows a complex personal side of emigration and immigration, not only the topic of trying to fit in to the new culture or society, but also how one’s identity changes or not upon leaving.

The theme of identity also pertains to the complexity of the film’s identity, and the compound identities surrounding contemporary cinema. Vidal made Ex generación in Mexico, while living in Cuba, with support from a Mexican fund, yet premiered it at the Muestra Joven in Havana, thus begging the question that persists over the works of the nuevos realizadores, and of much of contemporary film: is the short documentary still considered an example of Cuban cinema? With non-Cuban funding, filmed in Mexico, and the director currently residing off the island, Vidal has maintained his presence at the annual Muestra through the diaspora stories that he shares in this work, staying present digitally from afar challenging official definitions of the Cuban film corpus and the imagined community to include the Cubans in movement through digital technology.

V. Conclusions:

These two films embody the simple aesthetics, limited budgets, and socially critical works that define this generation of filmmaking, pushing the boundaries of both Cuban identity and film. While these artists have made exceptional changes in film, there are still many challenges that this generation faces that the nueva realizadora, María Elisa Leal, in a personal interview, explains. According to Leal the annual Muestra, while an important venue, is limited to six days to a specific part of Havana and as a result nuevos realizadores’ works do not garner enough visibility in the Muestra. The Muestra also remains connected to the ICAIC and does not have the independence that this generation of filmmakers wants and needs.

The ICAIC still holds the purse strings and has a level of control, albeit less due to digital technology. However the ICAIC faces a crisis that has become more pronounced with the April 2013 death of its original founder Alfredo Guevara, marking a new phase within the Cuban film community both within and beyond the ICAIC. As the ICAIC looks to reorganize behind closed doors, the island’s top filmmakers, actors, and nuevos realizadores have come together demanding a space at the negotiation table to redefine the state’s role in Cuban filmmaking through public letters, town hall monthly meetings, and discussions with the ICAIC. In the demands and negotiations with the ICAIC, the topic of carving a space for independent film is one of the most discussed at these meetings, especially since while independent film and the works of the nuevos realizadores are not completely illegal, their independent production companies are still not recognized by the state. Until they earn the independent status and space they deserve, filmmakers such as Vidal and others from his generation continue to create films such as these without the state’s complete approval, challenging not only the limits of film but also the definition of what it is that makes one Cuban.

Notes

1 See Jiménez-Leal, for more analysis of the

PM affair.

Works Cited:

Anderson, Benedict R. O'G.

Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991. Print.

Bubbles Beat. Dir. Aram Vidal, Kastalya& The College of William and Mary. 2012. Film.

Burnett, Victoria. “A New Era’s Filmmakers Find Their Way in Cuba.”

New York Times 4 January 2013. Web.

Castro, Fidel.

Palabras a los Intelectuales. La Habana: Ediciones del ConsejoNacional de Cultura, 1961. Print.

De Generación. Dir. Aram Vidal.Kastalya. 2006. Film.

Ex Generación.Dir. Aram Vidal.Kastalya. 2009. Film.

Farrell, Michelle Leigh. “Independent Cuban Filmmaking from 2003-2013: Aram Vidal’s Trajectory Within and Beyond Cuba: An Interview.” Special Edition: Global Cuba/Cuba Global.

Sargasso: A Journal of Caribbean Literature, Language and Culture (2013):35-53.Print.

Fernandes, Sujatha, and Alexandra Halkin. “Stories That Resonate: New Cultures of Documentary Filmmaking in Cuba.” 45.2 (2014): 21-23. Print.

García Borrero, Juan Antonio. “Vanguardia intelectual, siglo XXI y nuevas tecnologías.” Latin American Studies Association Conference. Marriott, Washington, DC. 1 June 2013. Conference Presentation.

Jiménez-Leal, Orlando.

El Caso pM : Cine, Poder y Censura. Madrid, España: Editorial Colibrí, 2012. Print.

Leal, María Elisa. Personal interview. 3 March 2014.

López, Ana M. “Cuban Cinema in Exile: The ‘Other’ Island.”

Jump Cut: A Review of

Contemporary Media. 38. June (1993): 51-59. Print.

Ponte, Antonio José. “Introduction.” Cubans in Movement: Toward a New Civil Society. Center for Latin American Studies NYU. King Juan Carlos Center, NY, NY. 4 November 2013. Conference Presentation.

Stock, Ann Marie.

On Location in Cuba Street Filmmaking during Times of Transition. Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2009. Print.

Zayas, Manuel. “The Institutional Crisis of Cuban Cinema: Independents are Back.” Cubans in Movement: Toward a New Civil Society. Center for Latin American Studies NYU. King Juan Carlos Center, NY, NY. 8 November 2013. Conference Presentation.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.