Artists' Utopia? Cuban Art Defined at The Eleventh Havana Biennial

Nikki A Greene

Newhouse Center for the Humanities

Wellesley College

ngreene@wellesley.edu

Key words: Havana, Cuba, Biennial, Cuban Art, Contemporary Art, Cuban-US relations

****************************** |

The beautiful decay and nostalgic charm of Cuba served as a counterpoint to the eleventh Havana Biennial, which offered some of the most innovative and fascinating works of art produced on the international stage today. The theme, “Artistic Practices and Social Imaginaries,” a deliberately general theme on the part of the curatorial team at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center in Havana, attempted to capture the multiple threads of collective identity despite international borders, the challenge of materiality of any given work of art, and the cultural significance of the different manifestations of performance.1 When the Havana Biennial began in 1984, only artists from Latin America and the Caribbean were invited to participate. However, by its second Biennial in 1986, the scope widened to include artists from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Ever since, the Havana Biennial has distinguished itself by its inclusion of “non-Western” art, and has since expanded to include more artists from Europe and the United States. Acclaimed international artists participated and were often present in Havana and these well-known creatives left their expected, dazzling impressions. Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović was on hand for the screening of Matthew Akers’s notably provocative eponymous documentary of her 2010 retrospective The Artist is Present at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. American photographer of Honduran and Cuban descent, Andrés Serrano exhibited a stirring show of his traditionally stark photographic portraits in Old Havana’s Fototeca. The eleventh Biennial, in fact, showcased 180 artists from 45 countries from May 11 to June 11, 2012. However, the curatorial and philosophical emphasis on Cuban and Cuban-born artists made the venue much more poignant as a result. Attempting to visit most of the galleries, museums and outdoor installations made this Biennial—off the well-trodden paths of Venice and New York—all the more special and well worth the pilgrimage to multiple locales.

American visitors were noticeably present throughout Havana, in artists’ studios, exhibition spaces, and public squares.2 There is now an international market for art from Cuba, and the country remains “on the cusp between socialist fundamentalism and neoliberalism.”3 This pseudo-capitalism—in order to rake in hard currency—has seen Cuba embrace tourism in the last 15 years. Since 2011, the country has also permitted thousands to run their own businesses in trades, restaurants and bed and breakfasts, but not the professions.

Greater cross-cultural artistic exchanges through shows—and sales—between Cuba and the US also means enhanced opportunities for Cuban artists to create improved conditions for their families, associates, and, sometimes, whole communities. As travel to Cuba becomes increasingly easier for travelers from the United States through academic licenses and “People-to-People” cultural exchanges, Cuban artists’ spheres of influence—and power—will continue to grow as will the precarious positioning of artists in articulating this mounting authority. In the Cuba Pavilion (Pabellón CUBA), one effective example of this kind of authoritative communication, Cuco Suárez’s Sospechosos (2011), showcased a security arch, whereby each passing visitor triggered a sensor which activated a rotating red light that flashed above while an ominous voice blared phrases like, “We know who you are.” The Havana Biennial served, then, as an excellent vehicle for artists of Cuban heritage to express sophisticated cultural and politically charged messages, through installations, public performances and sculptures.

At the Wifredo Lam Center for Contemporary Art (Centro de arte contemporáneo Wifredo Lam) in Old Havana, the administrative center for the Biennial, the compelling contradictions of the city of Havana prevailed in Carlos Garaicoa’s floor tapestries embedded with writing and slogans.

| Carlos Garaicoa, Fin de Silencio, 2012. Tapestries of cotton, wool, trevia-cs, lurex, and mercerized cotton yarn. Various dimensions. Gallería Continua, San Giagnano, Italy; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

In Fin de Silencio, visitors removed their shoes in order to walk atop four large rooms of the stitched representations and floor video projections of stone and concrete, cracks and grunge of Havana’s real terrazo sidewalks. The soft fabric yielded to the weight of entrants who chose to walk cautiously across or tentatively around the edges. What seems inappropriate and unusual becomes important and transformative as one’s own footsteps within the quiet, uniformed space operate alongside—and against—the knowledge of the actual noisy, broken sidewalks and streets of Old Havana outside the center’s walls. Moreover, as with so much of the work by Cuban artists exhibited throughout the city, the mimetic character of Fin de Silencio (The End of Silence) addressed the constrained political environment in Garaicoa’s choice of material and his implicit invitation for viewers/participants to tread over his creations. Bold inscriptions with words and phrases like “el pensamiento” (thought) and “la general tristeza negará placers” (the general gloom will negate pleasures) further emphasized the artist’s anticipation of visitors’ hesitations and a deliberate manipulation of those insecurities. One had a sense of not being sure of one’s footing over the decayed cracks and crumbling spaces, which speaks to the precarious nature of Cuban existence physically and ideologically.

Cuban-American artist Jorge Pardo arrived at the Wifredo Lam Center for the opening of the Biennial in May and returned for the closing in early June. He hired assistants to construct and paint wooden, geometric shapes continuously on-site at the center for his installation, Work in Progress. Pardo’s approach is much like that of Sol LeWitt, a noted American conceptual and minimalist artist who created highly geometric drawings, sculptures, and wall designs, and who habitually provided sometimes vague instructions to employees to carry out without his interference or even his physical touch, which allowed for interpretation by teams of artists of often complex arithmetic shapes. In the same vein, the workers at the Wifredo Lam Center dutifully followed Pardo’s plans using software installed on an older model computer. They cut and hung each piece on the wall to make a colorful, serpentine mural of whirling colors and patterns. The assistants, the computer, the machinery and the resultant mounds of dust were all on display via a window at one end of the gallery. Pardo, in effect, not only represented the process itself, but also conveyed conscientiously how in Havana, striking objects are produced daily as a result of long, patient work and a cooperative spirit.

A stunning installation, “Family Abroad,” and performance of Llegooo! FeFa! by the internationally recognized performance and photography-based artist, María Magdalena Campos-Pons, encompassed a similar spirit of togetherness. In collaboration with musician and husband Neil Leonard, Campos-Pons processed along the Malecón, the city’s iconic esplanade and seawall. While masked in protective white clay and dressed in a red, floral kimono, she gave away bread. Men have traditionally baked bread in Cuba, but more women are entering the profession. Using the pregón (the street-seller’s cry), she called out in concert with other vendors who sing throughout the streets to advertise their wares. Through this act, she explored how the female body challenges and reaffirms societal norms and religious practices, as she has successfully accomplished throughout her career. Campos-Pons, 10 of her American students, and 10 female bakers from Havana worked in partnership to bake bread in a local bakery for the performance and the gallery. In fact, before leaving Boston where Campos-Pons lives and teaches at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, she and her students learned the craft of baking bread and collected and wrapped donated items that were later arranged in the gallery at the Lam Center.4 The bread, the green, bundled donations, and the video projection of vendors highlighted the fortitude of Havana citizens to thrive despite limited resources and with a deep sense of cultural pride.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons and Neil Leonard, Llegooo! FeFa!: Familia en el extranjero/Family Abroad, 2012. Bread, cloth, and glasses on wood table with unknown, miscellaneous objects in plastic. Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

Another moving performance was by the two-man Cuban artist team, Los Carpinteros, who orchestrated the Conga Irreversible down the prominent Paseo del Prado, just two blocks from the capitol building. The parade offered a celebratory, yet moribund expression of the carnivalesque. Dozens of dancers and musicians donned in black—a deliberate anti-color move—danced, played music, and sang exuberantly in reverse movement past unsuspecting passersby. A possible nod to the high place given to the visual and performing arts in a country that, according to some, allows only narrow freedoms of expression, the conga was executed entirely backwards.

Manuel Mendive, perhaps the most famous and revered Cuban artist living in Cuba today, has perpetually set the tone and the stage, literally, for performance art in Havana. Born in Havana in 1944, Mendive has influenced nearly three generations of artists, including Campos-Pons. At the second Havana Biennial in 1986, he arranged the performance of “La vida,” which officially established for the contemporary Cuban art scene a genre of “body art” and “the performance as a valid mode of visual arts.”5 Deeply committed to Afro-Cuban culture and aesthetics, his paintings characteristically portray anthropomorphic birds and fish, along with Yoruba-derived deities (orishas), as recognized in Santería, like Changó, the god of fire, lightening, and thunder, or, especially Yemayá, the goddess of water, who also doubles as Caridad del Cobre, the patron saint of Cuba.

| Manuel Mendive, Aguas de Rio, 2009. Mixed media. 54 x 36 x 9 in. Mendive Studio & Gallery. Outside Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

As a result of his cultural philosophy and religious practices, Mendive blends seamlessly human bodies, the environment, and fine arts by periodically painting his signature forms directly onto the skin of dancers. For the eleventh Havana Biennial, Mendive orchestrated two performances, Las cabezas (The Heads), which departed from the Gran Teatro de la Habana on the Paseo del Prado, and a two-man dance at the Centro Cultural de Bertolt Brecht. For Las cabezas, semi-nude dancers processed in groups and were painted white from head to toe. Some flapped their arms seductively like birds; others marched decidedly while looking out at the crowd curiously like fish, all to a methodical drumbeat and all while making high-pitched, animalistic moans. Some performers also adorned half-meter, oblong, orange and blue polka dot masks that mimic the exaggerated, profiled heads that populate many of Mendive’s paintings and sculptures.

The more intimate environment of the exhibition gallery space at the Bertolt Brecht Cultural Center showcased two men who mysteriously emerged at separate moments from an opening of Mendive’s painted sculptural façade.

|

Manuel Mendive, Dance performance and metal sculpture. May, 15, 2012. Various dimensions. Centro Cultural de Bertolt Brecht, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

On a slightly elevated platform with barely one-meter distance between them and the audience, the men moved gracefully in front of the golden backdrop. A small screen above and to the right of the stage played a recording of the same men dancing. Similar to Las cabezas, Mendive painted their bodies, but in this case, they were completely nude and the men’s skin served as canvases of beautifully rendered, original art of the artist’s familiar elongated faces and marine-like figures that undulated with every twist, swoop, and lift the men made as they encircled, embraced, and carried one another. They occasionally looked out at the standing audience. Mendive, thus, blurred the lines between the distinction of people, animals, and artwork convincingly for those who were fortunate to witness the transformation.

As part of the exhibition, “Detrás del muro/Behind the Wall,” several sculptures and installations were integrated into the landscape along the Malecón and conveyed entertaining and introspective views of Havana. A play on words, “Behind the wall” of the Malecón alludes, metaphorically, to the only remnant of the Berlin Wall, as Cuba remains one of the world’s few Socialist countries, and entering and exiting for Cubans has not eased. For example, taking into account the readymade social environment of Havana’s own flâneurs, and, of course, tourists, Arlés del Río’s metal fencing plane silhouette, Fly Away (2011), deliberately directs the viewer beyond the breathtaking view of the northern horizon of the island. This ghost-like punching through of the giant fence in an airliner shape characterizes the frustrating process for some Cubans to travel freely in and out of Cuba without restriction. Esterio Segura’s Home-Made Submarine (installed in a blacked out tunnel along the Malecón) proffers another take on a voyage beyond Cuban borders. The artist’s interpretation of a sci-fi utopia wherein the Cuban spirit of “making do” through ingenuity and resourcefulness, expressed most outwardly in older American classic cars used everyday throughout the country, becomes realized in a reinvented car-submarine. Similarly aware of the longing for another place, Rafael Domenech’s sculpture, Possible Chances, stood as a series of red doors welded together to provide different perspectives on the city and its borders.

|

Rafael Domenech, Possible Chances, 2012. Metal doors. Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

As the Havana-born and trained artist put it: “Going through all the doors, the spectators perform the daily action of entering and leaving places representing my personal status of an immigrant.”6 The bright red paint, thus, may also refer to the Kafkaesque red tape for those who must cross the many thresholds of bureaucracy and communism in order to leave the island.

If one had to judge the Biennial’s recurring themes of travel, globalization, and rules and regulations based on a single location, then works at the Fortaleza de la Cabaña, on the other side of Havana’s harbor, not only demonstrated how Cuban artists deserve to garner more international recognition, but also confirmed the Havana Biennial’s rightful place in the international market for art lovers around the globe. Even the students’ work at the expansive Cubanacán college grounds of the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA) rivals seasoned artists from many countries. Unlike so many cases in the United States and Europe, where too many artists are simply left out of the dialogue, La Cabaña allowed each artist a significant amount of physical space. Nestled beautifully within the 18th century former fort, large white alcoves provided venues for installations of all dimensions. The fort historically also served as a prison, marked, then, for some Cubans as a place of “sadness, separation from loved ones, tears, months and years of captivity, overcrowded cells, lacking any sanitation, stifling heat, searches, harassments, beatings, bayonets, hunger strikes, death, one last hug, shootings…”7 Nevertheless, allowing for a few hours to walk around, the fort comprised some of the most brilliantly conceived and expertly executed artwork throughout the Biennial that often treated directly the contradictory nature of the show’s environment. Case in point, the much-adored, Havana-based artist, Alexis Leyva Machado, known as “Kcho,” retained four rooms at La Cabaña, including one that housed over a dozen elegantly posed boats, a recurring object within his oeuvre. Built in various sizes and placed upright, in La conversación/The Conversation,

Alexis Leyva Machade/KCho, La Conversación/The Conversation, 2012. Wood. various dimensions, La Fortaleza de la Cabaña, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

the boats held within the cell took on the tone of entrapment on the former militarized jetty, unable to escape to reach the nearby waters below. The artist installed in the adjoining cell, Lo peor del invierno/The Worst of Winter,

Alexis Leyva Machade/KCho, Lo Peor del Invierno/The Worst of Winter, 2012. Mixed media, various dimensions. La Fortaleza de la Cabaña, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

where he suspended from the ceiling several shark forms covered in discarded clothing along with suitcases and other travel detritus. Kcho made here a more direct comment on the fate of Cubans who unsuccessfully attempt to leave the island either by a makeshift raft, or by the even more desperate means of swimming.

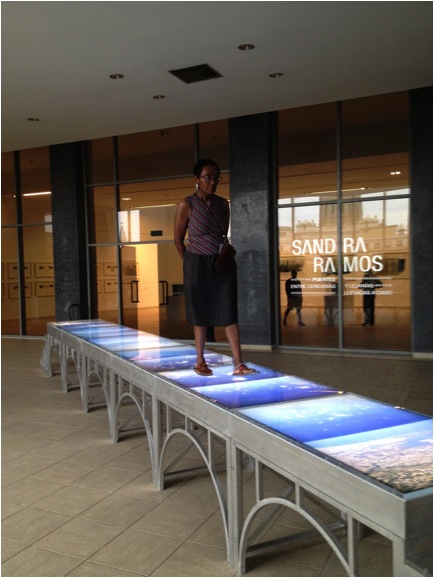

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes complemented the Biennial well and offered a critical part of the discourse. More Wifredo Lam paintings hang in a single gallery there than any other place on earth, including early figural and large-scale abstract expressionist paintings. As one of the most important modernist painters of the 20th century, his presence continuously serves as a foundation upon which contemporary Cuban artists build from, and expand beyond. Cuban artist Sandra Ramos’ small, but moving show Puentes (Bridges) at the museum showcased a stirring reflection on family, migration, and struggle between the United States and Cuba through a series of enlarged passports, a spectacular mirror book, and sculptural installations. In 90 Millas,

Sandra Ramos, 90 Millas (90 miles), 2011. Aluminum structure, digital prints, and light boxes, 60 x 90 x 600 cm. El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

Ramos tapped directly into the often-conflicting reactions to the strained relationship between the two countries and affected families through the construction of a six-meter bridge whose walkway contained aerial photographs encased below visitors’ feet, documenting the short plane ride between the Havana and Miami coastlines. Right in line with the Cuban art community and the spirit of the eleventh Havana Biennial, Ramos articulated the common sentiments of estrangement, loss, and survival by building a bridge where doors, planes and boats cannot do.

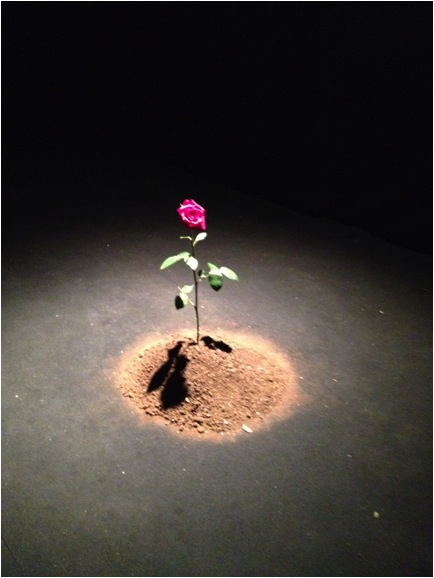

The politics of display continued to be heightened, not only due to the outdated infrastructure, but also more poignantly due to the ruins of a post-revolutionary ideology. At the Cuba Pavilion (Pabellón CUBA), for example, Niavy Pérez installed El pasaje (2007), a long-stemmed, red rose upon a mound of soil within a hall completely shrouded by makeshift black walls.

Niavy Pérez, El pasaje, 2012. Rose, soil, perfume. Pabellón CUBA, Eleventh Havana Biennial, Havana, Cuba. Photo, Nikki A. Greene |

|

A spotlight fell upon the flower from above, and each time a visitor approached, a lusty rose scent dispensed into the air. The rose appeared to stubbornly grow within the barren environment despite its circumstances, or better yet, because of them. The installation was at once stifling and intoxicating, and, therefore, more alluring within an almost terrifying darkness. Imitating the kinds of jarring yet seductive experiences of the city of Havana, Pérez translated accurately Cuba’s resilience. With the country’s slow transition towards greater flexibility in travel, increasing (though still quite limited) opportunities for home ownership, and growing access to capital, more visitors and investments, especially from the United States, will undoubtedly stream in over time. More Cubans will depart. Cuba will change as a result, for better or worse.

Notes

1 Jorge Fernández Torres, “Prácticas artisticas e imaginarios sociales,” Oncena Bienal de la Habana 2012, (Habana: Centro de Arte Contemporáneo, Wifredo Lam; Consejo Nacional Artes Plasticas, 2012), 16-21.

2 Victoria Burnett, “American Accents Being Heard on the Malecón,” New York Times, 18 May 2012, C1.

3 Kerry Oliver-Smith, “La globilizatión y la vanguardia/Globalization and the Vanguard,” in Abelardo G. Mena Chicuri, Cuba Avant-Garde: Contemporary Cuban Art from the Farber Collection/Arte Contemporáneo Cubano de la Colección Farber, Trans by Félix Lizárraga, Samuel P Horn Museum of Art, Gainsville, Florida, 2007, 18.

5 Adelaida de Juan, “En el monte suena,” La luz y las tinieblas (Sevilla, Spain: Escandón Impresores, 2010), 11.

6 Rafael Domenech as quoted in Juan Delgado Calzadilla, Detrás del muro/Behind the Wall, Cuban Arts Project, Havana 2012, 50.

7 Ileana Arango Puig, “La Cabaña, lágrimas y muerte,” el Nuevo Herald, http://www.elnuevoherald.com/2012/07/01/v-print/1240788/ileana-arango-puig-la-cabana-lagrimas.html, July 1, 2012.

|